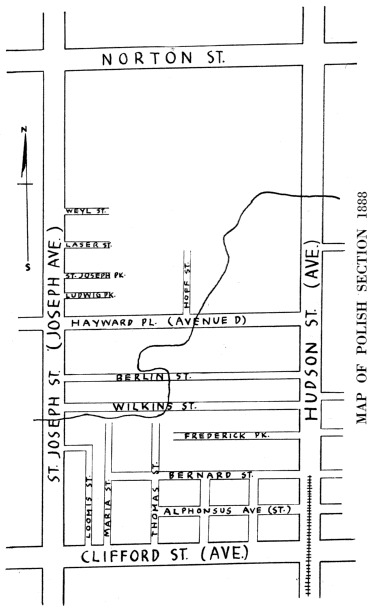

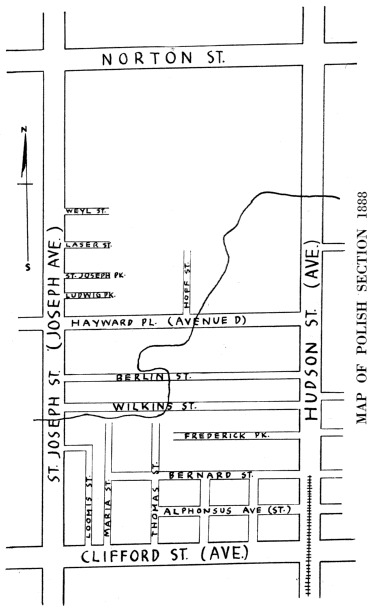

Map copied from Lathrop Plat Book (1888), showing the territory from Hudson Avenue westward to Joseph Avenue, which became the Polish quarter. The freehand line indicates the course of a creek, no longer in existence.

History of the Polish People in Rochester

PART II

Map copied from Lathrop Plat Book (1888), showing the territory from Hudson Avenue westward to Joseph Avenue, which became the Polish quarter. The freehand line indicates the course of a creek, no longer in existence.

The same, from Hudson Avenue eastward to Carter Street. The creek is continued and the small triangles indicate the location of open wells. Two other wells were used, which however, were not within the boundaries embraced by the above sketch.

IN the year 1887 the region about Hudson Avenue and Norton Street presented an aspect not unlike that which had impressed Sienkiewicz in his brief journey along the lake shore eleven years earlier. "Lowland meadows, overgrown with thick grass. cattails and last year's stubble" certainly were to be seen and the wild ducks of which he had momentary glimpses as "shadowy little crosses suspended between earth and sky" made seasonal visits to the little creek which ran through the Hudson-Norton tract. Wild ducks, in fact, were hunted on this very creek by Peter Bartylak, a Pole whose residence in Rochester dates back to 1875, and who has lived to see the old creek disappear beneath the surface of the fields. (13) and the fields themselves converted into a thriving community. The rural character of this landscape was considerably heightened by Moulson's Nursery, which occupied the entire north side of Norton Street from Joseph Avenue to Carter Street, a business enterprise which employed many Poles of both sexes during those early years, and which for that reason successfully resisted the urban development which rapidly broke up surrounding territory into building lots and streets.

Material facilities were almost wholly lacking. Horse cars, it is true, came down as far as St. Jacob Street, but beyond this terminal Hudson Avenue was but a dirt road with no sidewalks, continuing as little more than a wagon track into the nursery fields across Norton Street. Six wells furnished the only available water supply and modern sewage, of course, was completely absent. The farmlike appearance of the section will be seen in a reproduction, here published, of the map taken from the official Lathrop platbook of Rochester for 1888, on which the car line is indicated, the creek and wells having been added by the artist from contemporary records.

Of thoroughfares in a stage of development sufficiently advanced to be called streets there were but two which crossed Hudson north of Clifford Avenue. These were Bernard Street and Alphonse Street, which then rejoiced in the somewhat ponderous name of Alphonsus Avenue. St. Jacob Street and Frederick Park met at Hudson in the same dimensional relation as now exists, and Wilkins Street, or Avenue, extended at an angle across Hudson as an unnamed continuation. Hayward Place, which later became Avenue D, did not cross Hudson to the east. A few streets, such as Weyl, had been established at Joseph Avenue and in later years were continued to Hudson. On the east side of Hudson, however, not a single cross street existed from the lane opposite Wilkins Avenue to Norton Street. The very presence of the city line as far north as Norton Street, enclosing so wide a tract of agricultural real estate, serves to demonstrate the notions of municipal expansion then in vogue, which led the authorities to reach out for future communities, rather than to await their suburban formation and later absorption by the statutory redrafting of city lines.

Almost from the moment thin the site was chosen for St. Stanislaus Church, Rochester Poles began to assemble and establish living quarters in its vicinity. In the words of Jacob Jaworski, an early resident, the section was "like a hive to bees", an irresistible lodestone. Before the earth had been disturbed for the foundations of the new church, groups of Poles in high anticipation, came trooping from all sections of the city to do no more than gaze upon the vacant lot. In the case of four women, two of whom are living today, the very sight of this lot and the realization of community proprietorship, brought tears of joy, shed beneath the fruit trees of the nursery on Norton Street. Wojciech Kaczmarek. who still lives on St. Stanislaus Street, was one of the first arrivals and lived in a tiny frame house on Hudson Avenue near Avenue D, among the earliest dwellings on Hudson Avenue north of Clifford, while his more commodious home was under construction. Michal Gibowski also lived near the church site for some time before 1890 and recalls what was probably the first Polish picnic in Rochester, an affair held in the summer of 1889 at Scheutzen Park, for which an orchestra was brought from Buffalo, costing no less than $75.00, an impressive extravagance warranted only by the highly festive spirit which Rochester's first Polish picnic was designed to celebrate. This picnic, and the fact that parties were already being held in the temporary homes of families who were building permanent residences, leave no room for doubt that high activity had existed in the Hudson-Norton section for some time prior to the completion of the church edifice.

Societies too were formed at this time. The St. Stanislaus society and the Uhlans of St. Michael, which already have been mentioned. both existed before St. Stanislaus church was dedicated and the latter society continued for many years. A peculiar uncertainty exists as to whether the St. Stanislaus society was formed in advocacy of naming the new church after its patron saint, or came into being after the church name had been chosen. (14) Its organization, however, in October 1887, and the presence of other organized effort at this early date greatly aided in building a parish strongly united despite its small numbers.

With the completion and dedication of the church, numerous other families moved in. Some of these families, attracted by ties of blood and relationship, camefrom Buffalo and other sections of the state. In many cases, husbands who had arrived alone in America in the early '80s sent for wives and children after the formation of a community had become a certainty in 1887, and from that time through '90, '91, and '92, there were frequent happy reunions. Mrs. Josephine Szczupak, and Mrs. Walenty Paprocka, veteran Polish residents of Rochester, whose families were later united by marriage, came to Rochester within six months of each other in 1888 to join their husbands. The growth of the new settlement was thus accelerated by this powerful impetus toward the establishment of homes.

Money with which to erect dwelling houses at this time was none too plentiful, particularly when it is remembered that virtually the entire group participated financially in the business of paying for the new church, an accomplishment which was carried through with the periodic contribution of varying small amounts, sometimes as low as five cents at a time, faithfully and loyally donated. Most of the breadwinners of the community worked as laborers or in unskilled factory occupations, a condition not only due to lack of skilled training but to an appreciable extent the result of unfamiliarity with the English language. Furthermore, the small accumulations which many hard workers had managed to lay aside were depleted if not entirely exhausted in bringing wives and relatives from Europe. It is evident that the rapid development of the new community would have been impossible had not its members in the strength of a common purpose, practised the strictest and most well managed economy.

Much of the dispatch with which building was accomplished and not a little of the attractive character which still distinguishes the residential plan of the Polish quarter unquestionably is due to the energy and foresight of Stephen Zielinski. Having arrived in America with his parents in 1880, a boy not yet in his teens. Zielinski worked with his father as a mason and did his first independent contract job in 1888. From this small beginning grew the great general contracting business and lumber yard which for years have been an outstanding commercial feature of the Polish community.

Following the establishment of the church, Zielinski undertook buildingprojects almost without number. The first rough wooden sidewalks along Hudson Avenue were laid with lumber supplied by him. Families unable to manage the burdensome financing of new homes rarely failed to find in him either the needed assistance or helpful advice on their problems, and his contracting operations provided convenient and congenial employment for many of his fellow Poles. The scope of these operations is better realized when it is recalled that from five to seven hundred houses in the Polish section are Zielinski built houses, most of which were erected during the twenty odd years following 1890. (15)

From the point of view of the city at large as well as from that of the community itself, the extent to which Stephen Zieliniki was involved in the material upbuilding of the Polish section is highly important. His intense activity during the first years of settlement somehow typifies the Rochester Pole as a citizen. The desire efficiently to attend to its own work and to be economically self-sufficient has been a conspicuous trait of the local Polish group. It is more than probable that in the absence of men exemplified by Zielinski, alien interests would have seized the opportunity to exploit the new community through the medium of home building. Experience with foreign groups in many American cities has shown that from such alien exploitation are born the cramped and unsightly housing conditions which some day become the slums of our congested metropolitan centers. Fortunately, however, for Rochester and its Polish citizens alike, a contrary example was set by Stephen Zielinski, whose ambition to succeed financially was coupled with a genuine pride in the community he was helping to build, an example which his compatriots have closely followed in later building operations.

The prosecution of construction work was often impeded and the comfort of the new residents frequently assailed by a certain viscous substance which seems to have figured largely in the history of Rochester from earliest times. This was the mud. Spring rains and the gentle slope of Hudson Avenue toward the north combined to make the region about Norton Street a veritable swampland during the early months of the year. At such times men and women alike wore heavy rubber boots, and were obliged moreover to approach and enter dwellings through fields to the rear, rather than attempt the cumbersome and perilous navigation of Hudson Avenue. The teamster hauling his load of lumber to the site of a new home felt himself fortunate indeed to arrive at his destination without at least once having had to summon assistance in freeing his wagon from the mire. Accounts of the difficulties thus experienced are reminiscent of the eloquence with which Rochester's first chroniclers sought to impress upon future generations the unfathomable morass of Buffalo Street, in the spring "a kind of viaduct" (16), to cross which required sturdy legs and a stout heart.

Obstacles of a material nature, however, served only to increase the elation within the new group at the prospect of future development, and added zest to its labors. The Polish spirit of jollity, long repressed, sprang to impulsive expression, and numerous family and neighborhood celebrations were held on the strength of events which today seem unimportant. The completion of floor and roof on each new dwelling called for an exciting housewarming, at which the guests, attired in "Sunday best", sang native songs and whirled energetically over the bare floors in lively polkas, to the music of Walenty Paprocki's fiddle, a musical instrument which has become a fond tradition among the older residents of the Polish community. The acquisition of colorful uniforms by the Uhlans Society increased the popularity of impromptu parades, and religions holidays dedicated to saints and martyrs of the Roman Catholic Church were usually treated as community observances. Occasionally this festive spirit sought individual expression in surprising fashion, and the story is still told of a memorable uproar which broke forth in the wee small hours of a certain Easter morning, when one over enthusiastic citizen, annoyed at the impervious indifference of his compatriots who had gone to bed, conceived the happy idea of ringing the bells of St. Stanislaus Church, thereby sharing his exuberance with the world, an experiment which met with unexpected success.

As may be expected, the extent to which the group enveloped itself in its labor of settlement at first inspired the general adoption of European manners, customs and even dress. Men whose employment brought them into contact with Americans, to be sure, quickly learned the advantages of submerging their European earmarks beneath a veneer of standardization, but among relatives and neighbors at home they surrounded themselves as thoroughly as possible with the native Slavic atmosphere. The English language, which in a limited degree was used on the daily job, was more spoken about than spoken when at home, and the quizzical exploration of its mysteries by workmen who gathered at the evening fireside passed many entertaining and no doubt unwittingly profitable hours. Early struggles with this puzzling tongue still form a prolific topic of conversation among Poles who have since completely mastered it; there is the story, for example, of the new arrival who encountered, as his first experience with English, the word "picnic", the contemplation of which filled him with consternation, when he translated it to mean "no drinks", a connotation which Slavic phonetics, if not Polish grammar, unmistakably attach to this combination of letters.

The preservation of European dress continued for a time, more noticeably among the women, many of whom were more recent immigrants than the men. Voluminous dresses and shawls brought from across the Atlantic, more comfortable than the strange attire of Main Street, usually were made of material rugged enough to withstand the ravages of hard wear and represented traditions difficult to relinquish. Colorful peasant costumes were used on dress-up occasions, even by the men, a custom largely due to the fact that these costumes, in pattern and in color, possess various distinct meanings and constitute a sort of sartorial heraldry by which the provincial habitat and station in life of the wearer maybe identified.

Contacts with the city at large were few and limited to those which daily employment and the purchase of essential provisions made necessary. Weekly trips downtown were made by groups of three or four women, who came home with an assortment of bundles containing such foodstuffs as the establishments of Front Street, Franklin Street and the public market provided. These localities were important and widely patronized centers of trade for all of Rochester in those days, and their busy, cosmopolitan air appealed to the Polish housewife, who could thus obtain within the radius of a city block virtually everything edible that would be needed for the ensuing week. Much of this petty trading, it is observed, was done at the stores of Jewish merchants, another custom brought from Europe, where this type of business ordinarily was conducted by Jews; occasionally it happened that a Jewish proprietor was familiar with the Polish or some kindred Slavic language. In later years when economy became a less pressing consideration and time more plentiful, Poles became familiar with the department stores and specialty shops, purchasing a wide variety of articles and made fewer expeditions of the food-buying character, as markets and groceries came into being within the community.

Aside front such travel about the city as employment and provisioning required, the chief objects of attraction for the Polish group seem to have been the city parks. Parks, in Europe had been for the most part the exclusive prerogative of wealthy landowners and nobles, who opened their domains to the general public only on rare occasions; the spacious lawns and groves of Rochester parks, therefore, which were at all times free and open to every corner, furnished a novel and refreshing form of recreation which was enjoyed to the utmost. Highland Park with its reservoir and fountain seems to have been especially interesting, combining, as it does, beauty and utility.

Private tasks and the engrossing business of creating a community almost completely diverted attention from all forms of public entertainment, even in cases where the contrary might be presumed. Inquiry among older residents ceems to show that neither the performance of the Polish actress Modjeska (17) with Booth in "Richelieu" (1888) nor her appearance with Otis Skinner in a Shakespearean repertory (1892) attracted any interest on the part of Rochester Poles. "These things cost much money", said one veteran Polish citizen; "what money we had all went into our homes and church. Besides, the plays were in a language which we did not yet understand." Language was no barrier, however, to the enjoyment of music and the recital on March 16th, 1892 by a rising young Polish artist. Ignace Jan Paderewski, was attended by a number of his enthusiastic countrymen, the nucleus of a large and loyal following which to this day never fails to turn out for Paderewski concerts.

From the bustling activity of northern Hudson Avenue business enterprises soon began to emerge. As to which of these may claim the precedence of time any positive statement, for a number of reasons would be a hazardous assumption, (18) since development along these lines originated in several different quarters simultaneously. Among the very earliest, of course, was the Zielinski lumber yard on what is now Kosciuszko Street, which certainly existed as a going concern, even before the advent of markets and groceries, a fact further significant of the energy with which the problem of home building was being attacked.

Retail food stores soon came. One of the first of these was the Tomasz grocery, a small establishment, soon followed by others. A thriving grocery was operated also by Walenty Nowacki, whose various pursuits indicate a surprising versatility for he was at the same time organist of St. Stanislaus Church and volunteer teacher of probably the first group of children ever assembled in Rochester to receive Polish instruction. Another Nowacki, Antoni, unrelated to Walenty, for a time maintained a grocery on Hudson Avenue at the corner of the street which later became Northeast Avenue. A small grocery was conducted by Wojciech Kaczmarek in the front of his home on St. Stanislaus Street. Two markets at first supplied the community with meats, both of which were at first on North Street, later removing to the active center of trade on Hudson Avenue. These were the Schultz market, and that of Leo Drias, the former being soon transferred to the proprietorship of one Skrumak, who again established the business on North Street. From accounts of these early ventures, it is discernible that the turnover was high, in goodwill as well as in items of merchandise, and the stores themselves changed hands with noticeable frequency during the restless, formative period of settlement. With few exceptions, the commercial life of this section did not become appreciably fixed or permanent until about 1900.

This trend toward community sell-sufficiency has an interesting phase in the demand for various unique articles of diet pleasing to Polish taste which immediately sprang up with the appearance of Polish stores and foodshops, a demand which at first was met with some inconvenience and difficulty by resorting to isolated wholesalers in other large centers of Polish population. In a comparatively few years, however, Rochester had its own sources of supply for these specialties. Thus Thomas Brodowczynski, whose trade as a butcher had been learned in Europe, and who opened his market on Hudson Avenue in 1898, became probably the first butcher in Rochester to manufacture the several varieties of "kielbasa", or Polish sausage, a delicacy highly esteemed by Europeans, and much in demand by many native Americans who have become aware of its existence through Polish friends and acquaintances. The Brodowczynski shop, incidentally, is still a flourishing establishment at the corner of Hudson Avenue and Kosciuszko Street, numbering among its customers many non-Polish citizens from other parts of Rochester, to whom it is generally known by the singularly Gaelic name of "Brodie's Market". Thomas Brodowczynski, its founder, is still hale and hearty and with his sons, William, Walter and Stephen, still operates the market, which, with the single exception of the Zielinski lumber and contracting business, is the oldest commercial enterprise still active under its original proprietorship in the Polish community.

In addition to these and other retail shops which were started from time to time, there should be mentioned, of course, certain establishments devoted to the business of assuaging thirst, establishments without which no community, in those days, whatever its racial origin or background, would bave been quite complete. Doubtless pioneer honors in this field belong to the so-called Schneider Hotel just beyond the city line at the northeast corner of Norton Street and Hudson Avenue, which antedated the Polish community itself by a considerable number of years, and the frame structure of which was not finally demolished until ground was cleared for the Benjamin Franklin High School. Although at no time conducted by a Polish proprietor, and apparently very little patronized by the Polish group, its mere proximity to the settlement and the great number of years during which it remained have given this building the character of an accepted landmark in which capacity it may be said to figure in the life and history of its neighborhood.

At various times during the early life of the community there were three or four saloons conducted by nearly twice as many proprietors, from which it appears that this type of business as well often changed hands. One of these was operated by Gostomski, a Pole who had formerly resided in Buffalo and who, oddly enough, had some part in laying out and naming Kosciuszko and Sobieski Streets during his brief residence in the local settlement. More important, however, were the establishments of Albert Maciejewski and Lawrence Zwolinski, respectively, both of which have survived in other forms of activity, and in the meeting hall which adjoined the old Zwolinski bar was born the well known "Echo" musical society, which has played so important a part in interpreting Polish choral music to the city of Rochester, and now has a modern and attractive hall of its own on Sobieski Street.

The saloon, or bar, indeed, among Polish people occupied an important place in the life of the settlement for a number of reasons not connected with its function as a dispenser of beverages. It is noticeable that the successful barrooms invariably provided a hall or parlors where societies might hold meetings and groups congregate for purposes of neighborhood or community planning. Maciejewski Hall, which soon after its inception took the name of Pulaski Hall, has acquired during the years considerable historic importance as the early meeting place of numerous prominent Polish societies. Nor may it be assumed that such organizations regarded drinking as an essential part of their proceedings, for there are well authenticated instances of high indignation on the part of bar proprietors who had thrown open their parlors to homeless clubs of the neighborhood in the mistaken hope of thereby improving business.

Societies, in fact, during the first five or six years of the community's existence, were passing rapidly through preliminary stages and presently were to blossom forth as full fledged organizations, a development which could not well take place until a little of the ground had been cleared for their healthy growth. During these years almost the only organized groups having an official character were those which assembled under the leadership of church and priest and which pursued essentially religious or devotional objects. Roughly these may be listed as the societies of St. Casimir, St. Stanislaus and the Uhlans of St. Michael, which already have been discussed, the societies of St. Thaddeus, St. Joseph, St. Adelbert and the Sodality of the Holy Rosary, still an active unit in the parish of St. Stanislaus. The religious character of these organizations shows clearly how the early. Polish group clung to the church and thought of itself largely in terms of the parish, an essentially European concept.

As a matter of fact, all of the developments here discussed, covering the five or six years following the foundation of the settlement, represent in a sense, a natural reversion to European habits, and a strong impulse toward the duplication of European environment. In the light of years, however, it is seen that this reversion paved the way for a more genuine assimilation by imbuing in the group an understanding of civic responsibility, more willingly assumed by an organized social unit than by scattered alien individuals. Without a community, the isolated Poles or Polish families must sooner or later have been absorbed in the mass of the city's population by simple obliteration; with a community these inftuences began the assimilative process on a basis of economic independence, making possible in time to come contributions to the city of a cultural character which might otherwise have died in embryo.

Not many years had passed before the new community began again to turn its thoughts toward the political status of Poland, that ever vital issue which had burned in the heart of every Pole since 1795. A new organizational influence was on the horizon and formally took its place in the Rochester community on July 2nd, 1893 with the formation of Polish National Alliance, Group 216, Sons of the Polish Crown. Mention of this organization inevitably leads to a consideration of its parent, the Polish National Alliance in the United States, for the wide influence and commanding importance of the Alliance as a national institution affects the whole question of the Pole in America so profoundly that a brief exposition of its origin and nationwide background is not only appropriate but necessary in order thoroughly to understand many later developments within the local community.

The major struggle of Poland to regain her independence on native soil by her own efforts may be said to have culminated in the Polish-Russian revolution of 1863, the results of which were incalculably disastrous for the Polish people. Following this catastrophe, many responsible Polish leaders perceived the futility of further revolutionary movements (19) and sought to focus attention on the unification of the patriotic sentiment, wherever and by whatever means such unification might legitimately be pursued, in preparation for some future time when the events of history should disturb the precarious equilibrium of European politics sufficiently to interest the world in the freedom of Poland. This program of uniting Poles under a common banner of hope, in the United States took concrete form in the Polish National Alliance.

The five practical idealists directly responsible for this association resided in 1880 in California, where plans for the new organization were made and from which state the summons went out to Poles everywhere in the United States. Chicago, containing the largest American center of Polish population, became the headquarters of the Alliance and the Polish newspaper, Zgoda, of that city became its organ. The convention city of its birth, however, became Philadelphia by deliberate choice of the organizers, as having been the historic cradle of American independence. The motive of patriotic nationalism underlying the formation of this society from time to time has been supplemented by the assumption of other and more material functions, principally those relating to personal insurance of one sort or another. Attention to these matters, coupled with the complete accomplishment of its chief object in the political rebirth of Poland, has tended somewhat in the passing of time to obscure the aims for which it originally came into being, and it is refreshing and instructive to read again the stirring declaration contained in its constitutional preamble, which is here reprinted in full:

"When the Polish Nation, notwithstanding heroic sacrifices and sanguinary struggles, lost its independence and by a dispensation of Providence was doomed to a triple bondage and was divested of the rights to life and development by the superior force of the invaders, a portion thereof, most severely affected, voluntarily preferring exile to heavy bondage in the Fatherland, repaired, under the guidance of Kosciuszko and Pulaski, to the free land of Washington and, settling here, found Hospitality and Equal Rights.

"This valiant handful of pilgrims, not losing sight of their duties to their newly adopted country and their own nation, founded the Polish National Alliance in the United States of North America in order to form a more perfect union of the Polish people in this country, to insure to them a proper moral, intellectual, economical and social development, to protect the language of the Fatherland, as well as the national culture and customs from decay, and to promote more effectually all movements tending to secure, by all legitimate means, the reestablishment of the independence of the Polish territories in Europe." (20)

This interesting statement of principle reveals much of that quality which makes the Pole unique among American immigrants. By reason of his personal relationship to the Polish cause, his loyally to America has been a living concept resting always on two legs; one the fulfillment and enjoyment of liberty and the other an ambition for its future achievement, thus imparting constantly to the life of America a little of that "spirit of '76", in which the appetite for freedom is whetted by the uncertainty of its attainment.

The Polish National Alliance, therefore, became the first successful attempt at consolidation of American Poles. The method of organizing its various chapters or "groups", as they are called, is simple and orderly and with minor changes in procedure has remained the same from the outset, in localities having no group, five eligible persons may obtain a charter, and be assigned a number by satisfying certain formalities. The number assigned shows the order in which the group falls with relation to all other groups in the United States. In communities already having one or more groups, twenty-five charter members are required to form a new one, and any two or more groups in the same district may act as a unit through a representative committee or "commune", which also exists under charter from the parent organization and is distinguished by a number of its own, showing its chronological relation to other communes.

Eligibility to membership in the Alliance has been a troublesome question during several periods of its history and is an interesting subject in itself, although it is here impossible to treat it fully. Generally speaking the qualifications for membership are liberal; both sexes are welcomed; among adult groups new members must fall within the age limits of sixteen and sixty, and they should be of Polish birth or descent, although it must be admitted that this rule has not been rigorously enforced, The avowal of loyalty to the cause of Polish independence, when arising from unquestionable integrity of motive, has now and then opened the doors of the Alliance to racial aliens. The difficulties which have beset the society in this connection have sprung mainly from the conflict of its nationalist program with the spiritual and political internationalism represented in turn by the Roman Catholic Church and certain Socialistic parties, with both of which influences it has been involved in the past. The effect which these involvements had on Polish affairs in Rochester will be seen in later pages.

Rochester has had in all seven Polish National Alliance Groups, numbers 216, 396, 512, 783, 1020, 1145 and 1200, as well as Commune 27, representing several groups acting as one. Group 783. properly speaking, is the Polish Falcons Gymnastic Society, which joined the Alliance in 1906 but since has dissolved the connection, and Groups 396 and 512 have merged under the latter number, so that there are now but five Groups in the city, exclusive of Commune 27. Group 216, the oldest, celebrated its fortieth anniversary in October, 1933 at a jubilee celebration attended by Honorable Frank X. Swietlik, Dean of Marquette University, Milwaukee. who holds the highest ranking office in the National Alliance, that of "censor", or moderator.

CHARTER MEMBERSHIP P.N.A. GROUP 216. BACK ROW. left to right. Frank Felerski, Joseph Wardynski, Maximilian Sosnowski, Joseph Ciechanowski, Kazimierz Rajmer; MIDDLE ROW, left to right, Konstanty Zajaczkowski, Stanislaw Donke, Jan Adamski, Adam Piotrowski, Adam Winiewski, Stanislaw Pietraszewski; FRONT ROW, left to right, Joseph Sobieralski, Antoni Nowacki, Leon Kenczynski, Wladyslaw Paprzycki. Two other charter members, Joseph Walczak and Wincenty Wegner, are not in this picture.

At its organization in 1893, Group 216 numbered fourteen members, most of whom had been actively associated with the community from its beginning. These were John Adamski, Joseph Ciechanowski, who will be remembered as a charter member of St. Casimir's Society, Stanislaw Donke, Frank Felerski, Leon Kenczynski, who became the president, Antoni Nowacki, the storekeeper, Wladyslaw Paprzycki, who was elected secretary, Stanislaw Pietraszewski, Max Sosnowski, Joseph Walczak, the first treasurer. Joseph Wardynski, Wincenty Wegner. Adam Winiewski, also the first leader of St. Casimir's, and Konstanty Zajaczkowski. Two of the charter members, John Adamski and Stanislaw Donke, still reside in Rochester and at the recent jubilee there was conferred upon John Adamski by the National Alliance a decoration in recognition of his pioneer services, received by his wife in the absence of her husband because of illness. Donke is now president of the chapter. These men were all vitally interested in the cause of Polish liberty, and were primarily ooncerned with the business of uniting behind that cause the rapidly growing community in Rochester. Meetings were held at regular and frequent intervals at their various homes and the advancement of the Alliance, the establishment of a library of Polish books, the cultivation and development of Polish ideals in the new generation of American born Polish children in Rochester were freely planned. A library, in fact, was almost immediately established, the various members generously placing their few personal books at the disposal of the community. So far as is known, this was the first attempt at organizing a Polish library in the city of Rochester. With the impetus provided by this early contact with the nation at large through the medium of the national society and the energy supplied by further organization of the settlement, many of these plans have become realities.

Group 216 may be regarded as the first acknowledged organization of a purely secular character to enter the Rochester community, but the tendency to broader interests, of which its presence is an indication, is manifest in a number of other developments taking place at almost the same time. The matter of educating children was beginning to be thought of, and sentiment was becoming fairly general for a parish school, almost as soon as there could be gathered together a workable group of Polish children, Walenty Nowacki, organist of St. Stanislaus Church had marshaled these into a class, and had undertaken their instruction in the Polish language, using his own home for a classroom. By 1893 or 1894, however, this class had grown to awkward proportions and a local school was seen to be a necessity. The enactment by the State Legislature of the so-called Consolidated Schools Law in 1894, under which the provision for compulsory education of minors was much more strictly enforced, may have helped to bring this question to a head, since it is certain that the Polish settlement wished the instruction of its young to go forward under its own auspices, rather than suffer it to scatter the childhood of the community among many different and essentially alien schools.

It is of course inevitable that a movement of this nature should incline entirely toward a parochial school, and in fact the movement virtually originated within the church. By this time, some four years following the erection of the St. Stanislaus building, the financial burden had lessened somewhat and church and parish, under the leadership of Father Szadzinski, turned energetically to the task of raising funds for a new school. Ground was broken on August 26th, 1896 and cornerstone ceremonies took place on the 4th of the succeeding October. The school building, erected by Stephen Zielinski, reached completion during the winter of 1896-97 and on May 9, 1897 was dedicated by Bishop Bernard McQuaid, following a colorful procession from the church auditorium. It is worth noting that the number of participants in the dedication was reliably estimated at one thousand persons, a figure which demonstrates the rapid growth of the community during the nine and a half years since the organization of St Casimir's Society.

The interest displayed in this project on the part of the settlement as a whole was very great. The hall of the new school was for many years looked upon as a public meeting place and a large gathering in common oration of the 1863 revolution had been held in thu hull on November 29, 1896, (21) some months before the institution was dedicated. Before its formal opening, in fact, there was here founded on March 28th, 1897 another library of Polish books, a modest affair of but sixty volumes, with a very few periodicals; lectures were arranged in the school hall, at which small contributions were made for the purchase of additional publications.

First classes in St. Stanislaus School were held on May 10th, 1897, with a total registration of one hundred sixty pupils under the tutelage of four Polish nuns of the order of St. Joseph, Sisters Adelbert. Ladislaus, Barbara and Catherine, thought to be the first nuns of Polish nationality to teach in Rochester. Three of these faithful Sisters are still living, Sister Ladislaus in fact, being still a member of the St. Stanislaus faculty. Sisters Adelbert and Barbara are again personal associates and now teach in Elmira. In the early days of the school's history, the burden of many inconveniences was cheerfully home by the four nuns, on whose shoulders rested a new and heavy responsibility. Quarters could not at once be provided for their accommodation within the parish and for some time, during all sorts of weather, they were obliged to walk to and fro between the school building and Nazareth Hall on Jay Street. In time the upper floor of the school was made into a miniature convent for their use and of course there eventually was built the adjoining convent itself, in which St. Stanislaus teachers are still housed.

Identity with national Polish affairs was further strengthened by the organization of two new Alliance groups, the first on August 12th, 1897 of P. N. A. Group 396, a mechanic's and artisan's chapter, under the presidency of Frank Mietus, who, by an unusual coincidence, again occupied the office of president on July 14th, 1932, when this Group consolidated with Group 512, April 1, 1900 saw the organization of this Group 512 with Frank Mrzywka as president, under the chapter designation of "St. Izydor's Society". Investigation of the available records of the settlement for the fifteen years from 1890 to 1905 shows these three Alliance Groups to be the only officially organized bodies outside the direct guidance of the church. Whether this fact has any significance is a matter of conjecture. but it is evident that shortly before 1900. a situation was beginning to develop which was to sunder the community in a local quarrel so exciting as to attract citywide attention and interest.

The parish dispute of St. Stanislaus which flared intermittently for a number of years and finally resulted in the foundation of the Polish National Catholic Church of St. Casimir in 1908, will be well remembered by many Rochesterians. whether Polish or not, hut few, perhaps, realize the issues that were actually at stake or the underlying causes from which those issues proceeded. To properly approach an understanding of them requires the perusal of certain events, national in scope, and far flung in their effect upon the psychological temper of the American Pole.

Although Poland for centuries has been a predominantly Roman Catholic country and the mass of Polish immigration to the United States has been and still is of that religious persuasion, it is by no means surprising that the atmosphere and institutional structure of the Church in America should have presented unfamiliar features to the native Pole. His earliest church affiliations in this country necessarily were with alien parishes under alien priests; more often than not, for linguistic reasons, these parishes were German, a condition hardly calculated to satisfy the Pole, whose presence in a German parish frequently created problems which taxed the diplomacy and ingenuity of the priest to the utmost. Even the formation of Polish congregations sometimes did not solve these problems entirely, for the open agitation of the Polish cause within the Church could not well be countenanced by ecclesiastical authorities. Such open agitation, in fact, had not been countenanced even in Europe, with the important difference, however, that in Europe the responsibility for its suppression rested upon ruling governments and not upon the Church.

The organization of the Polish National Alliance, moreover, in a sense, embodied the desire on the part of American Poles to form a definitely lay organization, a tendency replete with latent provocation, although it awakened no immediate opposition from the clergy, who freely joined the Alliance in its early years. The later admission of Socialistic groups not in harmony with Catholicism, however, and the difficulties resulting from this development prompted the organization to divorce itself officially from all religious connections whatever, a course which brought about the immediate estrangement of the clergy.

The cry of Socialism, frequently raised during this period by the Church party in its criticism of the Alliance, while to some extent warranted by the changing attitude of the national association, was loosely employed and became an irritating barrage behind which more vital issues were fought out, in various local forums, and usually along personal lines. The Marxian internationalism of certain Socialist elements, indeed, soon afterwards awakened active hostility within the Alliance, a circumstance which largely diverted attention from disputes with the Church and subsequent events have removed many points of difference, although the Alliance still retains an essentially non-sectarian policy.

The presence of strongly Roman Catholic parishes in every Polish community in the nation, coupled with the rapidly spreading establishment and influence of the Polish National Alliance, made it inevitable that this course of affairs should reflect itself in local events everywhere among Poles. In these developments and in the psychological mood which they produced, it is seen that the stage was being set for the birth of a new religious medium, exclusively Polish and positively nationalistic in viewpoint, This was the Polish National Catholic Church in America, founded at Scranton, Pennsylvania in 1897.

The immediate issues which led to the organization of the National Church, at the outset were strictly local to the parish in which it originated, and concerned principally the right of the congregation to a voice in church management and to the selection of its own priest. Rev. Francis Hodur, the incumbent clergyman, who held the views of a majority of his parishioners on these matters, precipitated a controversy with his immediate superiors, as the outcome of which he withdrew from the authority of the Mother Church in America and established the Polish National Catholic Church. An attempt was made at first to conciliate the differences which had arisen, to which end Father Hodur went to Rome in 1898. His efforts there were unsuccessful and in consequence of the breach which his activities had created, sentence of excommunication was pronounced. Upon returning to Scranton, promotion of the National Church went forward, all relations with the Roman Catholic Church being forever broken in December, 1900, and Reverend Hodur became highest ranking Bishop of the new denomination, in which capacity he still serves.

In outward appearance, the National Church service and ritual cannot readily be distinguished from that of the Roman Catholic, except for the use of Polish instead of Latin in the Mass, and the greater emphasis which is placed upon Poland and her spiritual welfare in the less formal phases of worship. A reference to its credit statements will reveal a number of departures from orthodox Catholicism, centering chiefly about the fundamental divergence of theory respecting the source of temporal authority, which is held as proceeding from the parish instead of the priest.

From all of these circumstances it is obvious that the air of the Rochester community was charged with the possibility of church dissension long before the actual break came in 1907-08. The suspicion with which the National Alliance was regarded by the church extended to the parish of St. Stanislaus, and the efforts of Group 216 to take its place within the fold as a properly sanctioned society failed to meet with success. Group 396 at first did not arouse the disapproval of the priest, although it appears never to have been officially recognized (22). The number of parishioners represented by these P. N. A. affiliations was not large but contained men who were among the most active in the community, and who commanded unofficially a more or less suhstantial following. Factions sprang up, declaring sympathy with one side or the other, and the ensuing exchanges of argument were extremely heated, so much so, in fact, that mere words sometimes lacked adequate conviction and were supplemented by persuasive measures so emphatic as to attract the interference of the police.

From the initial cleavage of principle which led the Alliance Groups and the priest to look askance at each other, the controversy resolved itself altogether into a conflict of personalities in which the real issues were submerged beneath private animosities. The attitude maintained by Father Szadzinski, despite its unpopularity, was entirely consistent, and when the reproofs which he administered to his recalcitrant parishioners implied Socialistic motives to their activities, he was voicing the position of the Church at large, for which, in accord with ancient tradition, it had certain clear cut reasons. What the Church had not yet begun to realize, however, was that an undercurrent of anti-Socialist sentiment was already beginning to develop within the Alliance, and the characterization of Alliance members as Socialists, far from enlightening them as to the Church's position, unwittingly fanned the flames of dissension to still greater heights.

The formation of the Polish Socialist Alliance in Rochester in May, 1905, naturally did not help matters any with respect to the church dispute. Although this organization was openly non-religious and made no advances, pro or con, in the direction of the church party, its simple presence at this critical juncture of affairs tended to increase the disquiet by giving hostile factions fresh material for argument and adding to the general confusion of issues. The part later played by this organization in the development of the community was important and the attacks to which it was subjected during the early months of its existence must be attributed to the extraordinary tension which preceding events had created.

The specific differences which caused the dissenting parishioners to withdraw from St. Stanislaus and establish the National Church of St. Casimir were somewhat analagous to those which had arisen at Scranton in the parish of Bishop Hodur, and related to the participation of laymen in the allocation of church moneys. To a large extent these differences proceeded from the unfamiliarity of the European Pole with the mechanics of Church organization in the United States, more particularly, of course, New York State. Management of Church finances in Europe was regarded, in certain essential respects, as a governmental function, and church support was materially provided for in the levy and collection of taxes. Hence the financial demands of his parish on the individual were met, for the most part, indirectly through other agencies than the priest. Here, however, the entire responsibility for the maintenance of church property rested upon the shoulders of the clergyman, who was obliged to keep financial needs continually in the minds of his congregation in order to insure an adequate church income. The corporate structure of the parish, set up by state laws, in which the priest occupied the status of company treasurer under appointment by the Bishop, was a novel and mystifying innovation. It is not to be wondered at that these radical differences, which placed the congregation in a new relationship to the Church, somehow impressed the layman with the idea that he should exercise a degree of control over the parish funds.

Simple as this hypothesis appears, it of course strikes at the heart of that great theory of centralized authority and stewardship upon which rests the essential strength of Roman Catholic church government, and when the question arose in the St. Stanislaus parish it was met by the determined opposition of Father Szadzinski. It is altogether probable that the misunderstanding could have been amicably resolved, had it not occurred at a time when the entire Polish community was already seething with unrest. As it was, however, the anticlerical group resolved upon an appeal to Bishop McQuaid for a change of priests. In response to this appeal the Bishop personally addressed the parish respecting its duties and responsibilities, an admonition which unfortunately came too late to be effective. The dissenters thereupon appealed in turn to Cardinal Gibbons of Baltimore, the Papal Delegation in Washington and the Franciscans of Buffalo with no success.

At length a delegation was dispatched to Bishop Hodur of the National Church, who came to Rochester with Father Walenty Gawrychowski, a priest of that church on October 15th, 1907 and launched the organization of a new parish, which took the name of St. Casimir. In February of the next year Father Gawrychowski established permanent residence and soon afterward, on March 4th, 1908 the new church edifice in Ernst Street was dedicated personally by Bishop Hodur. The parish of St. Casimir has since taken an active part in all public affairs of the local Polish community and during the week of October 29th - November 4th, 1933, celebrated its twenty-filth jubilee, an affair which brought to the city a number of high dignitaries connected with the National Church in America. Its present pastor is Reverend Joseph Kula, who has been with the church since 1930, and the future of the parish as a vital factor in the life of the community seems assured.

Years of time have somewhat softened the hostilities which this memorable controversy produced, and even the few surviving residents who were actively involved seem inclined to look back upon its exciting episodes with whimsical tolerance. There is, in fact, a baffling diversity of opinion respecting not only the events themselves but the causes from which they sprung, due, no doubt, to the intensely personal character of the feeling engendered. Thus contemporary Polish developments external to Rochester, herein seen to have been the underlying causes of the breach are revealed in the memories and records of the present community as isolated threads, hardly perceptible until the dust of much irrelevant incident is blown away.

Apart from these outside influences, the very expansion of the Polish settlement from its bumble beginnings during the '8Os and '90s, provides a purely local explanation of these troublesome years. The tiny group of families which, in 1890, had founded a church, had now, in a sense, grown beyond the confines of a parish. The structure of the native American community, in which the church, although a harmonious part of the whole, is yet distinct from the body politic, was beginning to attract the favorable notice of immigrant leaders. Furthermore, the adoption of this idea by foreign settlements in the United States was greatly expedited by their rapid growth in a period of more or less free immigration, a fact singularly true of the Rochester Polish group. To such a group, therefore, the European system of social organization, symbolized by the parish, soon became an outworn chrysalis, which, in the course of a very natural transition, burst open to make way for its own offspring, the democratic and peculiarly American type of community.

The subsequent history of the Polish community in Rochester seems, indeed, to prove that the results of this transition, however painful may have been its processes, were almost universally beneficial, opening wide avenues of development, not only to the group as a whole, but to the church party itself. The air now having been cleared of that pollution whose fires had long smouldered beneath an apparently peaceful surface, many secular projects of a worthy character soon were undertaken, and St. Stanislaus Church was more freely enabled to embark upon its own ambitious program of church expansion.

To Part 1

![]() To GenWeb of Monroe Co. page.

To GenWeb of Monroe Co. page.