Is Rochester a "city of conformists," as its critics have charged? Is the voice of Rochester ever a subdued, disciplined chorus with no solo parts?

Is Rochester a "city of conformists," as its critics have charged? Is the voice of Rochester ever a subdued, disciplined chorus with no solo parts?Originally published

1946

Is Rochester a "city of conformists," as its critics have charged? Is the voice of Rochester ever a subdued, disciplined chorus with no solo parts?

Is Rochester a "city of conformists," as its critics have charged? Is the voice of Rochester ever a subdued, disciplined chorus with no solo parts?

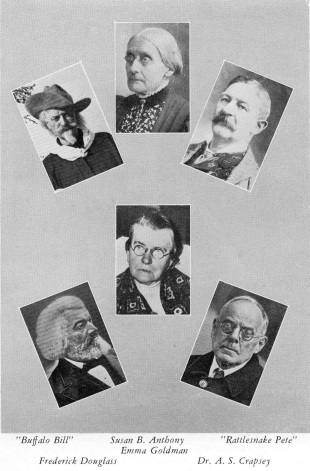

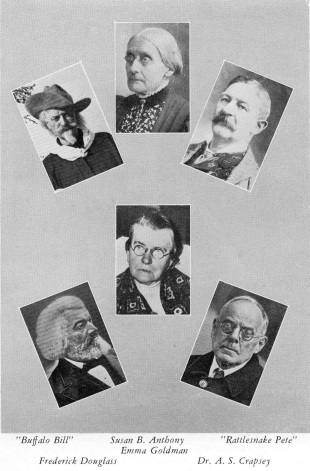

For the record, let it be cited that four famous crusadingrebels have called Rochester home. Amid hissings of derision andhowls of disbelief, their voices cried in the wilderness against thestatus quo. Each voice championed a cause and each in its timeechoed over the nation and sometimes beyond the seas. Only deathcould still the clarion tones.

The causes these dissenters championed were diverse. Theirpersonalities and backgrounds were just as dissimilar. They hadin common, eloquence, courage and a flaming zeal for a cause.They were willing to go to jail, to become outcasts for their beliefs. Money, popularity-they did not count. There was only thecause.

One of them was a Negro, born a slave and self-taught, whofor years with tongue and pen strove to unshackle his people andwho finally saw his cause triumph, at the cost of Civil War. Thatwas Frederick Douglass of Alexander Street and later of SouthAvenue.

The second was a strong-willed, tireless spinster who spent heradult life fighting for equal rights for her sex. Susan BrownellAnthony of 17 Madison Street died before her cause was fully wonbut in victory her name became its symbol.

Another was a storm-tossed figure with a lost and a dubiouscause. The poverty and oppression of her Russian childhood, hergirlhood experiences toiling long hours in a Rochester "sweat shop"for $2.50 a week helped to make Emma Goldman, once of JosephAvenue, the high priestess of anarchy; "Red Emma," a womanwithout a country who dedicated her life to the overthrow of thecapitalistic system.

The fourth rebel was a scholarly clergyman of gentle mien butwith a lion's courage when aroused. Because he dared to voice hisconvictions in defiance of the canons of his church, he was un-frocked, By virtue of a famous ecclesiatiastical trial, Dr. AlgernonSidney Crapsey of Averill Avenue, who had been an obscure parishrector became "The Last of the Heretics," a national figure.

* * * * *

Frederick Douglass was born Frederick Augustus WashingtonBailey in 1817, in slavery on a Maryland plantation, the son of awhite father and a Negro mother.

As a boy he was beaten by brutal overseers. When he took part in a plantation escape plot, he was jailed. He finally made a successful break for freedom-in a sailor's uniform. The Underground Railroad befriended him. He taught himself to read and write.

Called upon to tell his life story before an anti-slavery rallyin Nantucket, Mass., he spoke with such power and feeling thatthe abolitionists sent him on a lecture tour through Northern cities,including Rochester. After that tour he was threatened with a return to captivity and fled to England where two Quakeresses boughthis freedom.

In 1847 he came to live in Rochester where he had manyabolitionist friends. Here he founded his journal, "The NorthStar." The name of that anti-slavery paper came from the refrainsung by fugitive slaves:

His first issues were printed in the basement of the old AfricanZion M. E. Church in Sophia (Plymouth) Street. His young sonand daughter helped set the type. Later on his office was on thesouth side of Buffalo (Main Street) near the Four Corners. Hisfirst Rochester residence was in Alexander Street. He also lived onHamilton Street. Then he moved to the outskirts of the city, in SouthAvenue near the present Highland Park. That house burned down in1872.

That was an excellent location for the stationmaster of theUnderground. Douglass hid many a runaway slave in his home andin his office. There were many other hiding places in and aroundRochester, a strategic point on the invisible railroad because acrossonly 50 miles of blue lake lay Canada and freedom.

Through those ante-bellum years, Douglass was writing andlecturing. He was a spearhead of the anti-slavery movement. OldJohn Brown came to visit him and the two walked the PinnacleHills in deep discussion-the dignified Negro with the mane ofgraying hair and the grizzled white man with the burning eyes.The cooler-headed Douglass sought in vain to dissuade the fanaticalBrown from his scheme of seizing the Harper's Ferry arsenal.

When the plot failed and Brown was executed, Douglass wasin grave peril and again fled to England. At the outbreak of the CivilWar he returned and became an influential advisor to Lincoln andthe Union leaders. He was the first to suggest that the governmentuse Negro troops.

After the war he fought to preserve the rights his people hadwon. He was their spokesman and foremost leader. In the early1870's he moved to Washington where he held several federalpositions. He died in 1882 and is buried in Mount Hope.

In 1899 burly young Theodore Roosevelt, Governor of New York, came to Rochester to dedicate a fine tall monument to Frederick Douglass at the busy St. Paul-Central Avenue intersection. For 40 years it stood there. It is said to be the first such memorial to a Negro in America.

Now the figure of the statesman who was born a slave looksover Highland Park where the Station Master of the Undergroundonce sheltered so many fukitives and every year on Douglass Day hispeople, free men and women, gather there to honor his memory.

* * * * *

There are many living Rochesterians who remember Susan B.Anthony.

But she was an old lady when they were young, a tall statelyold lady in her black dress and white lace collar.

Her face was lined and a little stern. Sometimes her speechwas tart. She had known so many battles, so many defeats in half acentury of crusading for a cause. And complete victory seemed sofar away although her woman suffrage movement had gained groundin state after state.

She was a very famous old lady who had made speeches allover the land, before friendly crowds and jeering crowds, beforecongressional hearings and national conventions; who had metstatesmen and presidents and royalty.

But no matter where her campaigns carried her-and she wasactive almost up to the day of her death-her footsteps at battle'send always turned back to the roomy brick house at 17 MadisonStreet where her school-teacher sister, Mary, kept the home firesburning.

In those last days of her life, Rochester was proud of its most famous citizen. Many affectionately called her "Aunt Susan." Onher 75th birthday in 1895, 2,000 of her fellow townspeople crowdedthe Powers ballroom to honor her.

They did not deride her then as they had in 1872 when she leda handful of women to a little shoe shop at West Main and Prospect Streets to cast their ballots in violation of the law. At thetrial of the historic test case in Canandaigua Federal Court, the judgewho found Susan B. guilty, would not send her to jail as she desiredbut fined her instead. She never paid the fine.

In her later days when she had become one of the great figuresof the time, she was heard with respect, and sometimes with applause-never with the stunned silence that greeted her in 1852 when shearose in a state convention of teachers, two-thirds of whom werewomen, demanded and won the right to speak when only men hadspoken before.

One of Miss Anthony's biographers, Rhoda Childe Dorr, des-cribed the convention incident in these words:

"Straight and slim as a young pine tree in her fine broche shawland close fitting bonnet, she stood but her knees trembled and to hidethe shaking of the hands, she kept them tightly clasped together.But when she spoke it was in a firm clear voice:"

" 'Do you not see that so long as society says that woman hasnot brains enough to be a lawyer, doctor or minister, but has plentyto be a teacher, every one of you who condescends to teach tacitlyadmits before all Israel and the sun that he has no more brains thana woman?' "

She was not just the indomitable warrior for suffrage whosename leads all other Rochesterians in the history books. She was amany-sided, warmly human person, too.

First we see her a little girl playing around her Quaker home inthe Massachusetts Berkshires where she was born in 1820; then astrong-limbed teacher, able to manage the most unruly boys in herschool: called "the smartest woman in Canajoharie" with plenty ofbeaux. And there's the personable young woman who came to Rochester with her family on a canal packet in 1845 and who hoed corn,picked fruit and scrubbed clothes on her father's farm out GeneseePark Boulevard and Brooks Avenue way. But not for long, becausethe cause was always calling her to distant battlefields.

Her name is so closely linked to the women's rights movementthat many forget that she also crusaded for temperance and for freedom of the slaves; that she helped Clara Barton found in Rochesterin 1881 the second Red Cross chapter in America; that she led in thefight for admission of women to the University of Rochester and in1900 pledged her own life insurance to make up the last $2,000needed; that she marshaled the forces that brought about the election of the first woman school commissioner in Rochester, HelenBarrett Montgomery.

For fourteen years after her death in March, 1906, her successors invoked her name in the last great battle for suffrage and the 19th Amendment, "The Susan B. Anthony Amendment," became law.

Now her old home in Madison Street, where she wrote herspeeches, mailed out her proclamations, planned her campaigns, andwhence she went forth to stump the nation for the cause, is a national shrine-for the woman voters of America.

Every voting booth in which women cast their unchallengedballots also is a monument to Susan B. Anthony of Rochester.

* * * * *

When I was a small boy in a small village startling news came one fall day in 1901 from the Pan-American Exposition in nearby Buffalo. William McKinley had been shot by an anarchist with whom the kindly President was about to shake hands in the crowded Temple of Music.

I recall how excited the grown-ups were over the deed and how one of them said, and there was bitter anger in his voice, "This is the work of that anarchist Emma Goldman. The fellow who killed McKinley is her disciple."

Later on I heard and read much of "Red Emma," the "mostdangerous woman in America," for thirty years a veritable symbol ofanarchy, who was deported to Russia in 1919 because of her subversive activities in the first World War.

So when in 1932 it was announced that the exile, then inCanada, had been granted permission for a 90-day stay in America,and was to visit her old home in Rochester, I visualized a glamorous, cloak and dagger sort of person in the movie-thriller tradition.

Instead I saw a dumpy, gray-haired, seemingly demure, motherlyappearing woman, peering myopically through thick lenses. Butwhen she spoke, the pale blue eyes behind the glasses flashed sparksand you knew why they called her "Red Emma."

Addressing Rochester's leading forum, the City Club, she told that generally conservative audience that: "I am no more respectable than I ever was. It is you who have become a little more liberal." And she declared that "your city and the action of the State of Illinois in the Haymarket cases made an anarchist out of me."

Which sends us back along "Red Emma's" life track. She wasborn in the Russia of the Czars about 1869 and knew poverty andtyranny. She came to Rochester, a girl of 15, accompanied by asister. Another sister was already living here. The family lived inhumble quarters in St. Joseph Street, now Joseph Avenue.

She got work in a clothing factory at $2.50 a week for a 60-hourweek, an experience she never forgot. She became associated with alittle group of radicals who met in Germania Hall, and became afiery disciple of the left wing. She was deeply stirred over the brandof justice meted out in the Chicago Haymarket trials. She discoveredshe was a forceful public speaker.

Emma sought wider horizons. She divorced her Rochester husband, a Jacob Kershner, who had been a boarder at her home, and went to New York in 1889. Up to the time of her exile she called the big city home although she made frequent visits to her Rochester kin.

For 30 years, wherever class war flamed, the name of EmmaGoldman was linked to it, rightly or not, In World War I she wasimprisoned for obstructing the draft and inciting to riot.

During the postwar wave of feeling against "Reds" she wasdeported, with some comrades, to Russia. She did not stay there longand called the Soviet experiment "a doleful failure." She rangedfrom country to country on the Continent, writing and speaking.After marrying a Welsh miner, James Colton, she found a haven inCanada where she died in 1940.

She was an "unreconstructed rebel" against a capitalistic societyto the last, this stormy petrel that "Rochester helped make an anarchist.,"

* * * * *

For nearly a quarter of a century, the Rev. Algernon SidneyCrapsey was just another parish rector, a well-liked, faithful anddiligent shepherd of his flock at St. Andrew's Episcopal Church, butlittle known beyond the limits of Rochester.

Native of an Ohio farm and a veteran of the Civil War, he hadcome here, a youth of 26, from an assistant's post in Trinity Church,New York. He was a scholarly, mild-mannered man-but there waslatent fire in his eyes.

Around 1904, a new note crept into his sermons. The wordspread that the rector of St. Andrew's was preaching unorthodoxdoctrines. Dr. Crapsey was importuned by his bishop and otherchurch leaders to change the tone of his sermons. He did not do so.

The nub of the controversy was his denial of the miraculousconception of the birth of Jesus Christ. In his autobiography. "TheLast of the Heretics," published in 1924, Dr. Crapsey stated his case thus:

"I asserted that Jesus was born, that He lived as we live; that Hedied as we die; that the story of His immaculate birth was unknownto Him, to His Mother or to the early Christian church. For that Iwas tried and convicted and deprived of my pastorate. What washeresy in 1906 is now orthodoxy."

His trial before an ecclesiastical court in St. James parish housein Batavia in the spring of 1906 was a national sensation. Distinguished counsel made learned speeches. The chief prosecutor wasJohn Lord O'Brian of Buffalo. Defending Dr. Crapsey were Congressman James Breck Perkins of Rochester and Edward M.Shepherd of New York.

The rector appealed his conviction to a higher court and lost.St. Andrew's was packed when he preached his farewell sermon inDecember 1906 and cast aside his priestly robes.

He began lecturing before mass meetings in Rochester, "appealing to the enlightened conscience of mankind." He founded here a Brotherhood for Social and Spiritual Work. At first he had a large membership, including men of wealth and influence, but Dr. Crapsey's espousal of what then were radical economic theories alienated his conservative following.

His Brotherhood languished but the unfrocked clergyman, nowfamous, kept writing and lecturing. He traveled abroad. He wenton speaking trips, walking from city to city, a knapsack on his back.Once in Dunkirk he was arrested by a dim-witted "cop" as a vagrant.

The last years of this gentle-mannered old man with the thinning silver hair were spent in writing and study. Like the other"rebels of Rochester," he never yielded his convictions. Algernon Sidney Crapsey, the self-styled "Last of the Heretics,"passed away in Rochester the last day of the year 1937.

He may well have been called "The First of the Modernists"

See that car with the rattlesnake crest on one side and a klaxonin the shape of a serpent's head on the other? See the smilingman in it with the two huge St. Bernard dogs, the man with thedrooping gray mustache, the snakeskin coat and the wing collar?

That's Rattlesnake Pete.

See that ox-shouldered man riding an open carriage drawn bytwo prancing white horses, the man in the broad-brimmed hat, thelong curly hair, the gray imperial and the regal bearing?

That's Buffalo Bill.

See that blind old man shuffling along Main Street, tapping thewalk with his cane, muttering Bible verses, his alms cup outstretched,a placard bearing Scriptural texts suspended from his shoulders?

That's Blind Tom.

See that roughly dressed old man driving a mule hitched to aramshackle buggy, rattling down Front Street, laden with frogs' legsand water cress; the old man who growls imprecations at passingautomobiles?

That's Frogleg George.

* * * * *

But you will never see them or their like again. They are gonewith the Rochester of yesteryear.

Every city, as well as every crossroad hamlet, has its "characters," those who in one way or another stand out from their fellows. Some have that quality called "color." Others are merely eccentric. But they are "different," they are exhibitionists and everybody knows them and looks for them. And after they are gone, they become, traditions and are remembered long after more important-and probably more useful-citizens are forgotten.

Rochester has had its "characters," many of them. I think thefour with the picturesque monickers are the best remembered. Such colorful and really notable personages as Rattlesnake Pete Gruber and Buffalo Bill Cody hardly belong in the same category as such local eccentrics as Blind Tom Anderson and Frogleg George Priesecker save that they had these things in common-they were different from run of the mill folk and they added piquancy to the Rochester scene.

* * * * *

Rattlesnake Pete was Rochester's most colorful citizen. He alsowas one of its most famous.

For forty years his museum-grill that housed the strangest collection of curios in America was one of the city's showplaces.Thousands beat a path to 8 Mill Street, visiting notables, wide-eyedrustics, city-bred habitues.

Its genial proprietor whose powerful arms were scarred by ascore of snake bites was a master of reptile lore. He knew how andwhere to catch the serpents; how to treat victims of their fangs;how to extract their venom and oil and market them for medicine;how to use the hide for purses and handbags and the tissue-like outerskin as poultices; how to treat goiter by wrapping the bodies of harmless snakes around a sufferer's neck.

Pete Gruber learned his snake lore from the Indians who livedin the hills near his birthplace, Oil City, Pa. As a youth he caught acouple of rattlers, put them in a screened box in the restaurant hisfather ran in Oil City. People flocked to see them and his museumwas born. Young Pete and a friend built a miniature oil well andgold mine that, along with the snake box, formed the nucleus of hisfirst "Hall of Wonders."

After brief ventures in Pittsburgh and Buffalo, Gruber came toRochester with his growing museum around 1892. For eight monthshe operated in West Main Street near the old canal. Then he movedto Mill Street and held forth there until he died in 1932.

His musty curosity shop became filled to the eaves with fantasticexhibits. The hairless cow from India faced the 3,300-pound stuffedPercheron horse. There were tanks filled with snakes, jars of pickledbrains, three legged chickens, two headed calves.

Pete owned the meerschaum pipe once smoked by John WilkesBooth, Lincoln's assassin; the first electric chair used in New YorkState; the battle flag of Custer's last charge; a shingle from the Johnstown flood; the ax wielded by a wife slayer; the skull of the horse that carried Phil Sheridan "up from Winchester."

There also were the figures of the dying Indian, Cleopatra andthe asp, all kinds of small fire-arms and trick electrical devices suchas the one that shot out a padded fist at you when you dropped a coinin the slot or the gold piece on the bar that gave you a shock whenyour greedy hand touched it.

Add to this array, the rich personality of Pete himself and hisnational renown as an authority on snakes and it was little wonderthat when Rochester was mentioned, the question would follow:"Have you ever been in Rattlesnake Pete's place?"

Rochesterians traveling abroad found Peter Gruber's picture onthe walls of a hotel in Athens his name a familiar one in such far offplaces as the Swiss Alps and Shanghai.

Circus people were fond of Pete. But then he liked everybody and everybody liked him. He was always courteous, always a gentleman despite his forbidding nickname.

There was never any rumpus in his place. Pete had been a boxerand a swimmer of repute in his youth and roisterers respected hisphysical strength and the steel-nerved courage of the man who hunted rattlers in the Bristol Hills and who had survived the bites of 29rattlers and four copper-heads. And there was always at least one,sometimes four, of the giant St. Bernards around their master, In the days of the excursion trains country folk always made abee line for Rattlesnake Pete's. They talked about its wonders formonths.

After Pete's death in his Averill Avenue home at the age of 75,his old showplace, shorn of his colorful personality, became justanother place. His collection was sold and scattered.

Only in memory does the snake-bedecked car with the St. Bernards and their shaggy-mustached master ride the streets of Rochester. When Peter Gruber died and his museum was no more, a bright square faded from the patchwork that is the Rochester scene.

* * * * *

Col. William Frederick Cody was a resident of Rochester foronly two years. Buffalo Bill, the Iowa-born soldier, hunter, Indianscout, crack marksman, superb horseman, picturesque showman, oneof the last of the frontiersmen, really was a world citizen.

His ties with Rochester in his lifetime were strong and sentimental ones. His three children are buried in Mount Hope and during the 1890's and the early days of this century, nearly every year he brought the tinsel splendor of his Wild West shows to the city he had called home when he was on the threshold of his career as a showman.

Buffalo Bill settled his family here in 1874. Two years beforehe had started on the road with his Western melodrama, "The Scoutof the Plains." In 1875 the show played here at the old GrandOpera House, now the Embassy.

Rochester never saw a more colorful troupe-nor probably aa worse show. It was melodrama without plot or sequence. But ithad lots of shooting and Wild West atmosphere and young Rochester loved it. It also thrilled at the sight of the actors, such frontiercelebrities as Texas Jack and Kit Carson Jr. and the Indians whowore white shirts when offstage but refused to tuck them in theirbuckskin breeches.

The Codys had three children then, Arta, 9, Kit Carson, 5 andOrra, 3. Mrs. Cody was a tall serious woman who found life withthe Colonel never dull but sometimes difficult for Buffalo Bill's feetoften strayed down the primrose path and through swinging doors.Like John L. Sullivan, one of his slogans was "drinks for the house!"

The family first took rooms at the Waverly House, (now theSavoy) in those days a fashionable hostelry. Then they moved to ahouse at 434 Exchange Street, now torn down. They also lived at 10New York Street and in another dwelling across the street.

A handful of gray-haired Rochesterians may remember the BillCody of the 1870's. He was in his prime then, a magnificent physical specimen, straight as a pine tree who walked with cat-like grace,despite his bulk. Add to that carriage, the inevitable big hat, a blackbroadcloth, long tailed coat, boots that shone like burnished brassand the charm of the showman's manner and you have as dashing afigure as ever clicked heels on Rochester sidewalks.

Young Kit died here of scarlet fever and Cody never got overthe loss of his only son. Orra's grave was dug beside Kit's in 1883.In 1904 the Cody's made another sad trip from the. West. Arta haddied at the age of 38. The ashes of Johnny Baker, Buffalo Bill'sfoster son and show partner, also rest in Mount Hope. Buffalo Billhimself sleeps in a tomb hewn out of Lookout Mountain nearDenver.

Whenever Cody brought his Wild West shows here, before hegathered with his old cronies at Lafe Heidell's rendezvous in WaterStreet, he visited the three graves in Mount Hope. It was here that hepatched up his long estrangement from his wife. Rochester alwayshad a high place in the heart of the old plainsman.

And there is many a Rochesterian no longer young in whosememory linger pictures of a gallant figure on horseback, waving astupendous hat, and the glory of his tents that brought them the oldWest, Indians in full panoply of paint and feathers, gaudy-shiftedcowboys on spotted ponies, twirling lariats.

* * * * *

For 40 years the tap tap of Blind Tom's cane was a familiarsound on Main Street. The sightless old man in the heavy canvassuit, peddling his religious tracts, was as much a part of the downtown scene as the Four Corners or the old Arcade.

Everybody knew him. Most everybody spoke to him. Somedropped coins into his extended cup. Some helped pilot him acrossintersections that were busy, even in the horse-car days. But he neversaw a single face that went with the voices that said, "Hello Tom."

Thomas Jefferson Anderson was blind from the day of his birth,in 1847, on the present site of the Milner Hotel in South Avenue. Hespent part of his boyhood in a New York City institution where helearned the Braille system and took organ lessons.

Upon the death of his father, he returned to Rochester. Penniless, he begged in the streets until a friend set him up in a news standin the old Reynolds Arcade. He augmented his earnings by carryingadvertising signs on Main Street.

Blind Tom married a devout woman who persuaded him to become a "sandwich man for the Lord." So the last 15 years of his life, he was in his own words, "a Gospel carrier," selling religious pamphlets. He wrote-or somebody wrote for him-a book called "Blind Tom's Life," which he hawked along with his other wares. After he "got religion," he had a burning desire, never realized, to preach in Rochester.

In 1911 a group of Rochester business men bought a little farmnear Camden, N. J., and gave it to Tom as a haven for his decliningyears. In a few months he was back on Main Street. Somehow hehad been swindled out of his farm.

In his late years he spent much of his time sitting on a nail kegin a blacksmith shop on the south side of Spring Street.

One winter morning in 1913, Blind Tom was found dead in his room in an East Side lodging house. Among his effects was $300, mostly in small coins, enough to insure a proper burial for the "Gospel Carrier."

When in 1934, a Rochester poetess, Elizabeth Hollister Frostpenned an ode for the city's centennial, she put the shuffling oldblind man in distinguished company with this stanza:

* * * * *

Frogleg George-that name calls up memories of an old man,an old mule, and an old buggy-and an older Rochester.

It brings back a picture of an unkempt, grinning old fellow, whocarried a market basket over each arm as he vended the frogs' legs,watercress and sassafras he had gathered. The clatter of his oldmule's hooves on cobblestones and the rattling of his venerablebuggy once were as familiar sounds downtown as the tap of BlindTom's cane.

He was born John Priesecker but few knew his real name andeverybody called him Frogleg George. For years he was a leadingsupplier of that gourmand's delicacy, frog legs. He snared the frogsin the swamps and ponds west of Rochester. He had a regular salesroute but Front Street was his principal stand.

George once lived in the city but neighbors' protests against hisnumerous swine, geese and other livestock drove him into the hinterland of Gates, nearer the frog lairs he knew better than anyone else in all Monroe County.

The old man whose balding dome was covered by a greasy felthat in summer and a cap in winter was something of a showman andoccasionally would devour a live frog to the edification of FrontStreet bystanders.

When the frog leg business fell off he relied on the sale ofwatercress and herbs. Once his popcorn wagon was a familiar sighton Main Street on Saturday nights, Sundays at Lincoln Park and atevening neighborhood fiestas.

Frogleg usually wore a smile but not when the automobile wasmentioned. "That invention of the devil," as he called it, was his pet hate.

Twice he was its victim. The first time his lightless equipagetangled with a "devil wagon" one night in 1921 out the BuffaloRoad, he was only slightly hurt, but he lost a prize cane he hadalways carried. The second time, in 1931, an automobile killed hiswell trained mule, Jenny; smashed his buggy and sent the old frogvendor to a hospital with grievous injuries.

Other woes beset him in his old age. His wife died and a Chilifamily took the infirm old man into their home during his last years.He was 76 when he died in 1936 without any known relatives, anondescript figure, but a well-remembered one.

* * * * *

There's another familiar figure, one of different caliber, whohas been missing from the Rochester scene these 12 years.

Remember tall, ramrod-straight James B. Rawnsley who neverwore a coat or hat, winter or summer? Even on the coldest daysyou'd see him in front of his physical culture studio in South Clinton,clad in his inevitable sweat shirt. No ear muffs or scares for ruggedJim.

He had been a noted trainer of bicycle racers in the heyday ofthat sport. The last 30 years of his life he ate no meat, subsistedlargely on fruit, vegetables and nuts. Walking races was his specialty.He observed his birthdays by taking five mile hikes. On one of hisnatal days he dashed up and down the stairs of the 12-story GraniteBuilding, to prove his wind was good.

He lived to be 76, the exact age of Frogleg George who atewhatever was handy and ignored all rules of health and hygiene.

* * * * *

In the days "before the other war," a motley array of eccentrics lent comedy relief to the downtown scene. There was round-faced Tommy Swales, delivery boy extraordinary who would amuse the sporting gentry with his impersonations, notably the one of Pitcher Christy Mathewson's windup. Another was angular "Nutsy" McFarlan, the shadow boxer who imitated John L. Sullivan, Corbett and other fistic greats, but always with the same stance.

Front Street was the forum where held forth "Fish Bob," a fish peddler of English lineage who claimed to have been born in Africa of missionary parents. Bob could quote the Scriptures fluently but when in his cups, he would mingle his Bibical verses with florid invectives in a mad potpourri of words.

There was "Matches Louie," who once peddled matches downtown and later opened a fortune-telling office in the Powers Block. He lived in a shack along the Erie Canal near Broadway with a bodyguard as eccentric as himself. When he died in 1913, he was found to be worth some $30,000.

Remember Johnny Heisel, courier for Barney Feiock, dealer inlegal beverages? There's a tale oft repeated by old timers aboutJohnny. Once he was sent to deliver a live rabbit in a basket to an East Side address. Somehow the bunny sprang out of the basket andas Johnny watched the fleeing animal, he snarled contemptuously:"Run you fool, run. You won't get to the right place. You don'tknow the address."

Another Main Streeter of yesteryear was Peanut Joe who formany years sold peanuts at Main and Water from a rowboat gailypainted and set up on trestles about breast high. Quotations fromShakespeare larded his philosophical chatter.

Strictly a police character was "Chicken" Murray who chose tospend most of his days as the guest of Superintendent Bill Craig atthe County Penitentiary. He grew so fond of the flock of "pen"chickens he tended he could not bear to be separated from them.

These are only a few of the "different" Rochesterians of thelong line that began with the picturesque Indian Allen. The Rattlesnake Pete, Buffalo Bill and Jim Rawnsley type towers above the rest. Yet each was in his own way a showman. And showmen are long remembered.

The time has come to talk of many things-of clothing and of shoes; of dental chairs and lenses and a Kodak King.

The time has come to talk of many things-of clothing and of shoes; of dental chairs and lenses and a Kodak King.

Look down upon Rochester from some lofty height like the Pinnacle and you see a city almost covered by a great canopy of trees. It is hard to realize that you are gazing at one of the key industrial centers of America. Rather it seems one vast park.

Yet Rochester, even in the beginning, was a mill town. Industrystill is the keystone of the city's arch, the foundation upon which thewhole house rests. Silence the lathes, presses, forges, drills, thewhirling belts, the throbbing engines and you muffle the very heartbeat of Rochester.

There are tall industrial oaks in this tree-canopied city. Thegreat plants whose specialized products are known all over theworld were not always there.

They did not just grow, like Topsy. Men planted them herebeside the Genesee and nurtured them in early critical years. Oncethe tall oaks were small acorns.

Those men were practical men, yet dreamers, too. They werepioneers. The founders in many cases fashioned with their ownhands the children of their own inventive genius. Most of them werecraftsmen, masters of their trades. Some had brought Old Worldskills with them across the seas.

They were not eloquent crusaders, stumping the country for acause. Yet even as the reformers, they in their own unspectacularway, resisted the status quo. They sought a better way of doingthings. They sweated over blueprints, they tinkered with gadgets intiny shops, in sheds and attics. One of them mixed chemicals in akitchen sink. Later on they called him the Kodak King. They knewdefeats and discouragement. But in the end they evolved many adevice that did much to alter a nation's way of life.

Nor were they colorful like the "showmen" of the precedingchapter. Picturesque characters seldom have to stare into the blackness of sleepless nights, trying to figure out ways of meeting nextweek's payroll.

Yet I think in the story of their early struggles there are elements of drama, part of the saga of America.

It is noteworthy also that with a very few exceptions the majorindustries of Rochester were founded in Rochester by Rochester men.

* * * * *

The alliterative combination of flour and flowers has longbeen associated with the name of the city. It does not tell the wholeindustrial story by a long shot.

Once Rochester might well have been called "The Shoe City,"For 50 years it was one of the leading shoe centers of the nation, regarded as foremost as a producer of women's and children's qualityfootwear. Shoes are still made in Rochester, quality shoes, but notin the oldtime volume.

The industry began in 1812 when Abner Wakelee, who hadmade shoes for Washington's army, opened a cobbler's shop in Buffalo Street. He bought his leather from a local tanner and peggedon the soles after whittling out the pegs himself. The stiffness of the square-toed brogans he made were eased by liberal use of bear's oil,abundant in that day.

A pioneer factory was that of Oren Sage, whose cutters, handstitchers and bottomers sat in a circle in one large workroom. Tokeep them amused, the proprietor and an assistant took turns readinga newspaper to them. Over a century later, musk floated throughwar plants for the same purpose.

Jesse W. Hatch of Rochester in 1852 revolutionized the shoeindustry by inventing a machine for sewing uppers on shoes, hitherto stitched by hand. The demand for shoes for Union soldiers in the Civil War boosted the number of shops here from 7 to 25.

In 1908 there were 52 shoe manufacturers and wholesalers,Rochester brands were famous. But evil days came. A disastrousstrike in 1922, the insistence of Rochester manufacturers on qualityin a mass production age and the shift of industry to the Midwest,nearer the source of supply, combined to wither an industrial oakthat for long years was among the tallest along the Genesee.

Mention Rochester almost anywhere and men will say, "Oh, yes,I'm wearing a suit made in Rochester." A mighty bastion on the city'sindustrial ramparts is the men's clothing industry, which employssome 13,000 workers.

Which is a far cry from 1812 and Jehiel Barnard, sitting crosslegged on his stool, fashioning the first suit ever produced in Rochester. It was made for Francis Brown, the miller, out of a piece of fulled cloth Brown had brought from Massachusetts. The bill was 20 shillings.

There were only custom tailors until around 1840 when a woman named Baker opened a little shop in Front Street where shemade boys' trousers and sold them at 25 cents a pair. A tailor on thestreet, Meyer Greentree, wooed and won her and he took over thepants business, later going into the general manufacture of men'sclothing. Thus out of a little pants shop sprang the famed Rochesterclothing industry.

* * * * *

Let's go back to the 1870's and a modest home in Center Park.By the light of a kerosene lamp a young man is experimenting withemulsions for photographic plates in the kitchen sink of his widowedmother's house.

By day he was a bank clerk. By night he was a research scientist. He was a spindly youth who looked like a bank clerk. His namewas George Eastman and he became the Kodak King.

His interest in photography led to his experimenting. Othershad made dry plates which were an improvement over the old wetplates but nobody had devised any way to coat them save by hand.Eastman invented a machine for doing the job.

With that machine he went into business in 1880, on the thirdfloor of a building at 71 State St. He had six people on his payroll.For the time being he kept his job in the bank.

In that humble cradle was born the Eastman Dry Plate Company, which became the Eastman Kodak Company, which became anindustrial colossus, one of the great corporations of America, withacres of plants that employ 30,000 workers in Rochester alone.

* * * * *

When a young woodworker, John Jacob Bausch, in 1853 losttwo fingers on a buzz saw, he turned to his other trade, that of grinding lenses, As a result the greatest optical plant in the world todaysquats on the bank of the Genesee River.

He was 18 then and had learned both his trades in his nativeGermany whence he came to America at the age of 14. He had beenmarried only seven weeks when his fingers were amputated. He had only $7.50 in the world. But he had some loyal friends. One wasHenry Lomb, who with other fellow countrymen, raised $28 to setBausch up in business. It was a little optical shop in a corner of ashoemaker's place in the old Reynolds Arcade.

Lomb became his partner, they perfected new ways of grindinglenses, the business flourished and that was the beginning of theBausch & Lomb Optical Company, biggest in its field.

* * * * *

Back in 1851 two other young men, George Taylor and DavidKendall, began making thermometers, in an old building at 11 Hill(now Industrial) St. They were the entire staff, production, officeand sales departments. After they had made enough instruments tofill a fair-sized trunk, they would put on their beaver hats and go outinto the highways and byways peddling their stock. That was thegenesis of the Taylor Instrument Companies.

William Gleason had only 50 men on his payroll when he madehis first machine tools in a shop on Brown's Race near the upper fallswhich powered his plant. He did all the designing himself, as wellas directing production. Today the products of the Gleason Works,which is still in the family, are sold all over the world.

A bleak woodshed in Gregory Street was the birthplace of theTodd Company, founded by two brothers, Libanus M. and GeorgeW. Todd, in 1899. There the first check protector was devised. Itsounded the doom of "the penmen" crooks. The Todd brothers aregone but they lived to see the business that started in a little woodshed become one of Rochester's major industries.

In 1908 when people were saying "the new fangled horselesscarriage won't last," young Edward A. Halbleib founded the Rochester Coil Company in a basement at 167 N. Water. His idea was to make electricity serve in place of the hand starting (and arm breaking) cranks, oil lamps, magnetos and rubber bulb horns of the day. He interested other men and they set about perfecting the basic ideas of the present automotive starter, lighting and ignition systems. Thus was born the North East Electric Company, now the Delco Division of that industrial gargantua, General Motors.

Frank Ritter was making furniture with the skill he had learnedin the Old World, in a modest shop on the river flats just off St. PaulStreet one day in 1887 when a dental supply dealer and an inventorcalled with some drawings. They asked him to make from that design, a new, scientific and revolutionary dental chair. He did it andthe result is the big plant of the Ritter Company, out West Avenue.

In 1884 Caspar Pfaudler, an ingenious mechanic for a firmknown as the Consolidated Bunging Apparatus Company, and hisassociates knitted their brows in deep thought. They sought a sanitary container that could be used for the vacuum fermentation process for making beer Pfaudler had developed. They found the answer-a glass lined tank-but first they tried out a cast iron tank,coated with glass enamel. A crowd of scientists was on hand for the.demonstration. It was a molten failure. Then they evolved a glasslined enameled steel tank and success crowned their efforts.

The huge Stromberg-Carlson Company began with the pooled savings, $500, of two Swedish-born employees of the Chicago Telephone Company, Alfred Stromberg and Androv Carlson, who in 1894, started a phone equipment shop in Chicago. In 1902, the plant, then a thriving business, was purchased by Rochester capitaland moved to its present site in Culver Road. Here this firm, now ofworld-wide fame, had its greatest development although it is not a"native son."

The present Yawman & Erbe office equipment plant coversmany acres. The first "plant" that Phillip H. Yawman and GustaveErbe set up in 1880 was a room 20 by 30 feet on the second floor ofan Exchange Street building.

In the late 1890's S. Rae Hickok was working his way throughcollege by making watch fobs for his fellow students. Like GeorgeEastman, he used his mother's kitchen for his first "assembly line."He baked the enamel on the fobs in her oven, Today Hickok products are sold all over the globe.

Probably the oldest manufacturer in the city is the James Cunningham & Son Co. It was 108 years ago that James Cunningham built his first phaeton in a little shop in State Street.

And these are only a few of the small acorns that grew into talloaks with chimneys and long payrolls beside the Genesee.

Almost from its establishment, the United States Patent Officehas been flooded with the brain children of Rochester inventors.Most of the photographic apparatus in use today, much of the opticaland other precision instruments came from Rochester.

A Rochester patent attorney, George B. Selden, bore the title of"Father of the Automobile." The story goes that around 1870 ahoof and mouth disease which crippled the horsecar system so thatfour out of every 100 transit horses were laid up inspired him toprovide a mechanical substitute for horses. Anyhow, by 1877 he hadbuilt what was hailed as the first and compact internal combustionengine. He is credited with being the first to bring together all thefeatures essential to a practical gas-driven car.

He did not take out his patent until 1895 and thereafter formany years he had a virtual royalty monopoly over the automobileindustry. Henry Ford challenged Selden's claims and won out in alengthy litigation that was a sensation of the 1900's.

Did you know that:

The first voting machine was invented by a Rochesterian, JacobH. Myers and used here for the first time anywhere in the electionof 1895?

The first mail chute was patented by Architect James G. Cutler after he had included it in his plans for the Elwood "skyscraper" at the Four Corners in 1889?

Bishop & Codman, who hitherto had made plowshares, made the first fountain pen here in 1849?

The first gold tooth was the handiwork in 1843 of Dr. J. B. Beers, a dentist with offices in the old Arcade?

That Josephus Requa of Rochester was "the father of the machine gun"? His "Requa Battery," tried out in the waning days of the Civil War, consisted of 25 gun barrels joined together which fired 20-ounce minnie balls, supplied by a cylinder operated by foot power. Tt took five men to operate it but it fired 300 shots per minute and that was real "fire power" back in 1865.

The Street car transfer, the fuzzy pipe cleaner and the custom of placing lighted candles in windows at Christmas time all were originated by the debonair and versatile J. Harry Stedman?

A Rochester physician, Dr. Charles Forbes, devised the individual communion cup and it was used for the first time in Central Presbyterian Church in 1894?

* * * * *

There's still another field in which Rochester industrialistspioneered.

Back in 1881 when hours of labor were from 7 a. m. to 6 p. m.six days a week, Alfred Wright was making perfume in a factory inState Street. He was a deeply religious man. When his workmentold him they did not attend church services on Sundays because theywere too tired, he ordered his factory closed at noon every Saturday.

He was the first manufacturer in America to institute the Saturday half holiday.

Forty-one years later another forward looking industrialist, Malcolm E. Gray of the Rochester Can Company established in his Greenleaf Street plant, for the first, time in American history, the five-day week. Henry Ford studied the plan and adopted it. Malcolm Gray replied to criticism of the innovation at the time: "The five-day week is fundamentally right and is bound to be universal in industry."

He was somewhat of a prophet as well as a trail blazer.

To next chapter

![]() To GenWeb of Monroe Co. page.

To GenWeb of Monroe Co. page.