It is August 11, 1874, the trotting horse is king and all roads lead to the Driving Park.

It is August 11, 1874, the trotting horse is king and all roads lead to the Driving Park.Originally published

1946

It is August 11, 1874, the trotting horse is king and all roads lead to the Driving Park.

It is August 11, 1874, the trotting horse is king and all roads lead to the Driving Park.

Even at daybreak, the highways are acrawl with buggies, carriages, surreys, farm wagons, a tallyho or two. Special trains arerolling toward Rochester from every direction. Far and wide thehandbills have proclaimed the opening of "the fastest mile trackin America."

The hotels and boarding houses are crammed. Many visitorsgreet the dawn from tents pitched near the park. Some have sleptin the open.

The inaugural day dawns bright and clear. A light rain duringthe night has put the track in perfect shape. Flags flutter from theimmense new wooden grandstand and from the long stables andsheds back of the freshly painted high board fence. The cream of the nation's horseflesh and of the, harness racingdrivers are here. The stakes are high, $40,500, in premiums, for thefour-day meet.

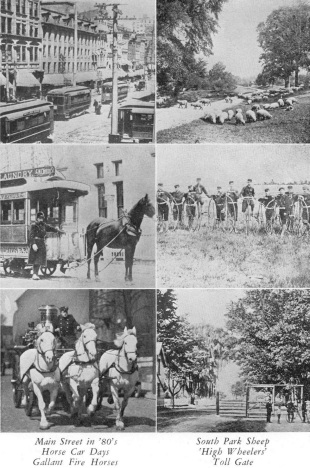

Long before starting time, the hegira to the Driving Park isunder way. The horse cars on the Lake Avenue line, the onlyroute near the grounds, cannot begin to handle the crowds. Thesteamers Jarvis Lord and Stranger ply the old Erie canal from uptown, jammed with passengers at 15 cents a head. The streets arechoked with hacks, carryalls and private rigs and hundreds walk thethree miles from the Four Corners.

More than 10,000 are in the stands when the starting bell rings.Many more are perched on the railroad embankment, in trees andother vantage points.

High carnival is in the air. Hadley's Band strikes up "MarchingThrough Georgia" and the war veterans in the crowd, conspicuousin their dark suits and wide hats, join in the stirring chorus. Grantis in the White House, the GAR is in the political saddle, they areat the races and all's well with their world.

Inauguration day at the Driving Park is a brilliant success butan even larger crowd is on hand the second day and through thestands creeps the tenseness that precedes a great sporting event. Forthe free-for-all, with its $5,000 purse, brings to the post some of theproudest names in the racing world: Goldsmith Maid, AmericanGirl, Judge Fullerton, Henry.

The night before, Bud Doble, an ace driver of his time, hastold an awed crowd at the Ayers House in Mill Street near the Central Depot, and incidentally the headquarters for Major Barker's "selling pools," that:

"I shall drive the Maid tomorrow and she will break her ownrecord of 2:15½, fastest ever trotted.

Bud Doble makes good his boast. The Maid, sound and fleetdespite her 18 years, shows her heels to the Girl, The Judge andHenry are outclassed. The crowd goes wild when the Maid's timeis posted. The grand old bay has hung up a new world's record, amile in 2:14¾.

It is the first of three such marks to be recorded at the DrivingPark in its 21 years of racing fame.

* * * * *

The Western New York Agricultural and Mechanics DrivingAssociation was born in February 1873, when a handful of sportsmen met in the old National Hotel, on the present Powers site. It was the golden age of the trotting horse. The names of the great Dexter and Rarus were hallowed ones. Many Rochesterians owned race horses. The old Union Race Course, out Park and East Avenues, had given way to Vick's flower gardens. The stage was set for a new deal in harness racing.

The movement was led by George J. Whitney, the miller; Patrick Barry and James Vick, the nurserymen; Mortimer Reynolds and others. It aimed, not only to have one of America's fastest race tracks, but also a fairgrounds where the agricultural and industrial products of Western New York could be displayed.

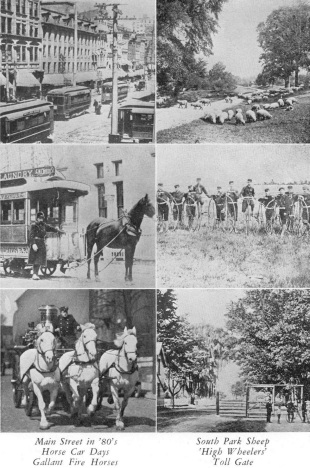

Seventy acres were purchased at $500 an acre. The tract was bounded by Driving Park Avenue, formerly McCracken Street,Dewey Avenue, the New York Central tracks and the present BryanStreet. The buildings cost $70,000. Their builder was George W.Aldridge Sr,, father of the Republican boss of a later era. Boyd'shotel rose within the grounds as well as exhibition halls, stables, andhitching sheds. A baseball diamond was laid out.

For years the Driving Park was a fair ground as well as a racecourse. Several state fairs were held there and noted orators thun-dered at the crowds.

The association, despite its auspicious start, soon found the going heavy and in 1878 after a foreclosure action, a new group, headedby Frederick Cook, the brewer-politico, took over the reins.

* * * * *

Then came the glorious days of the Driving Park, the era of theGrand Circuit and the exploits of Maud S, queen of the tracks. Excursion trains ran directly to the grounds. Thousands stormed the ornate entrance with its two kiosks where the southern link of broken Dewey Avenue ends today.

On Aug. 12, 1880, six years to the date after Goldsmith Maid'striumph, Maud S, racing against time, set a new world record at thepark, a mile in 2:11¾. A few minutes later St. Julien tied the timeon the same track. There were two joint monarchs of the turf and ahuge cardboard sign, lettered "Fastest Time Ever Made," was cut intwo and a half given each driver.

A year later, on Aug. 11, 1881, Maud S's flying feet again hitthe glory stretch. She clipped off a mile in 2:10¼, "fastest time ever made." The joy of her owner, William H. Vanderbilt, was unrestrained. The railroad tycoon had come to Rochester in his private car with a large party and Maud S had done him proud.

Again the name of Rochester's Driving Park was on the lips ofevery follower of "the sport of the kings."

John R. Gentry, Joe Patchen, Lulu and Jay Eye See, all famousnames in their day, raced at the park and added to its luster.

Bookmakers who followed the circuit from city to city set upquarters at downtown hotels and large amounts of cash changedhands. There was another group of more furtive circuit followers.They were the men who set up their tripod tables along the northside of Driving Park Avenue, then a footpath. There they swindledgullible rustics with their "three shell game" until police drove them away-to a new location.

* * * * *

But drab times lay ahead. The prize total dwindled, the turflords sought greener pastures and in 1895 the Driving Park saw itslast Grand Circuit race.

Still it was not deserted. There were sporadic racing meets,staged by the "Gentlemen's Driving Association." Circuses, amongthem Barnum & Bailey's and Buffalo Bill's, exhibited there for years.The old park housed bicycle races, track meets and other athleticevents.

In 1885 it was the scene of a sham battle between "Union" and"Rebel" armies, with all the participants veterans of the GrandArmy. The proceeds went toward the fund for the monument thatstands in Washington Square today-and of course, the blue-cladforces won the battle.

Ten years later the Lake View Wheelmen wound up a mammoth bicycle parade before the Driving Park stands.

In 1899 those stands went up in flames. In 1903 there was another foreclosure action and three years later the tract was cut upinto building lots.

Now there are snug Tenth Ward homes with neat lawns andflower gardens where once "the world's fastest time was made."

Now the Driving Park lives only in old scrap books, in yellowing newspaper files and in the memories of men, some of whom as boys worked their way into that wonderland by carrying buckets ofwater for the horses or peddling programs.

The old park also lives in a way that torments present daymotorists. Because of its old boundaries there's a jog in DeweyAvenue that creates an effective traffic bottleneck in the rush hoursat the street still called Driving Park.

I like to think that on August days down around Dove andLark Streets, or Archer Street, named after the last promoter of thepark, one can hear the ghostly beat of flying hooves, the clang of astarter's bell, bands playing old and forgotten tunes, the roar fromthe stands and the desperate imploring voices of the drivers as theylean far forward in their sulky seats, urging on the trotting greatsof yesteryear.

* * * * *

Crittenden Park, the old county fair grounds south of the city,took up. the torch after the Driving Park's course was run. But itnever burned so brightly there, It was only a half mile track with noMaud S, no Grand Circuit.

Yet in the early 1900's, thousands flocked out Mt. Hope Avenueto the park on the high ground, then in the Town of Brighton, andbounded on the east by Mt. Hope Avenue, on the west by LattimoreRoad, on the north by Crittenden Boulevard and on the south byRossiter Street. There the Rochester Driving Association staged racing meets, usually for a week in July and for a time under the aegisof the Central Trotting Circuit.

There linger memories of the 2:14 pace and the 2:30 trot; thespecial trolleys that ran to the grounds with Hebing's Band aboard,playing "In the Good Old Summertime," the vendors of whips; theother echoes of the horse and buggy age.

That age was fast fading. Noisy interlopers invaded CrittendenPark; racing automobiles, and motorcycles and strange contraptionswith wings that soared like birds over the river. King Horse totteredon his throne in the new era of machines and speed.

A bearded Baptist governor named Hughes outlawed race trackbetting and the Chicago bookmaker who had bought the park threwup his hands. Fire swept the buildings. Grass crept over the trackand in 1914 it went the way of the Driving Park-cut up into building lots.

* * * * *

So the curtain fell on the harness tracks yet King Horse refusedto abdicate the Genesee domain.

For one colorful Labor Day week of 22 Septembers he reignedin Rochester. Thirteen years have passed since the silvery call of abugle has echoed through the ring at Edgerton Park but Rochesterwill not soon forget the glitter of its Horse Show.

The show began in 1911 as part of the Rochester IndustrialExposition, which that year moved into what was then ExpositionPark after three years uptown in Convention Hall Annex, which, by the way, was built for that purpose.

Mayor Hiram Edgerton's dream of a combined fair and horseshow was realized after the city acquired from the state the old Industrial School property on the North Side. That prison-like institution with its grim 20-foot stone wall and stockade was converted to civic uses after the school for wayward boys was moved to Industry.

The first 15 years of the "Expo" and the Horse Show were thebrightest. But too many red figures spattered the ledger and theHorse Show of 1933 was the last. The Expo struggled on until 1938when it died, a bankrupt.

* * * * *

Let's wander back to one of those halcyon Labor Day Weeks, inthe 1920's, in the heyday of the Horse Show in Rochester.

Again a red coated ringmaster stands erect in the green oval and familiar figures are greeted by the stands. Patrician, derbied ReggyVanderbilt confers with Jim Sam Wadsworth and Norman VanVoorhis in the judges' ring. There's a Wanamaker daughter drivinga sleek chestnut. There's Sir Clifford Sifton who has brought thepick of his stables across the lake from Toronto. Two perennialfavorites get a hand. The reinswomen are Mrs. Loula Long Combsof Missouri and handsome Jean Brown Scott of Pennsylvania.

The best horseflesh of the Genesee Valley, "land of the huntingsquires," vies with the best of American and Canadian stables. Thehunter and jumper events with their occasional spills bring thecrowd to its feet. The "Touch and Out" event is a super thrill.

The cavalrymen of Troop F with their Cossack-like riding;mounted State Troopers galloping through a ring of fire-they satisfy that part of the onlookers who know little of the fine points ofharness and saddle judging.

The Tea Tent of the elite sparkles. There the arbiter of Roches-ter society, Mrs. Warham Whitney, presides. The newspapers aresprinkled with the proud pictures of Mrs. This and Miss That "whotoday were among. those who poured at the Tea Tent."

And there's the Expo, the midway with its barkers, Creatoreleading his band with wild gesturing; the prize calves, pumpkins andquilts, the horseshoe pitching, the latest in washing machines.

If it chances to be Governor's Day at the Expo, Al Smith may bethere, flashing his wide grin at the voters.

Uptown there's revelry by night. Famous names are on thehotel registers. Jimmy Walker, dapper, irrepressible, is feted at the Valley Club. Or maybe it is Richard Evelyn Byrd, natty in his Navywhites, who's the guest of honor.

And now Horse Show Week is only a pleasant memory.

* * * * *

But in peacetime summers many smaller horse shows hold forth where once there was one big one. The love of fine-and fast-horseflesh that is bred in the bone of the Valley of the Genesee persists in its metropolis.

Many Rochesterians, ordinary folk as well as gentry, ride as a pastime. Many own their own mounts. Rochester is well represented in the stands-and at the pari-mutuel windows-at Batavia, Hamburg, Fort Erie and more distant tracks.

"Horses, horses, horses." Remember the old song?

And there are those who have never seen a horse race, yet arebrilliant students of racing form and follow "the sport of kings"assiduously through the medium of "cigar stores" that have neversold a cigar.

PRESENTING a fanciful dialogue between a reincarnated graybeard and his grandson:

PRESENTING a fanciful dialogue between a reincarnated graybeard and his grandson:

"Sonny, I'll meet you at the Liberty Pole at noon."

"Grandpa, don't you know the Liberty Pole blew down in thebig wind of '89?"

"The old Arcade was torn down 14 years ago. There's not beena postoffice there in 55 years."

"Joe Jefferson is at the Academy of Music in 'Rip VanWinkle'."

"Say, that theater was razed in 1903 and Joe Jefferson has been dead these 31 years."

"Then we'll see Maude Adams in 'Little Women' at the Lyceum."

"Lyceum? There's a parking lot where the Lyceum went down in '34."

* * * * *

Yes, Grandpa, they are gone, those landmarks you knew sowell, that were so encrusted with tender memories of your youngerdays. When old timers like you saw them depart, one by one, theirhearts were sad. They missed them as they would a familiar facethey would never see again.

Changing times, the match of business, sheet old age took theirtoll as well as fire and the elements. They are gone but not forgotten, the ancient landmarks. They still stand sharp and clear alongan invisible trail-the path of memory and of tradition.

* * * * *

Once upon a time the Liberty Pole was as much a Rochestermile post as the Four Corners.

For 30 years it stood proudly on the hill at the west corner ofMain and Franklin Streets. It was 101 feet tall, three feet in diameter and was surmounted by a brass ball and an arrow weather vane.On its lower reaches were blocks for climbing the wooden shaft. The Liberty Pole was raised when clouds of war were darkening the national sky, on the eve of July 4, 1859. During the CivilWar the flag waving atop the pole told Rochester of every Unionvictory. It floated at half mast on Memorial Days. For years theLiberty Pole was the scene of Independence Day celebrations.

The Liberty Pole became a Main Street fixture. The whole triangle at Main, Franklin and North Streets took its name. Across the street on the McCurdy store site was the Farmers' Hotel and countrypeople used to say: "I'll meet you at the Liberty Pole." No onedreamed but that the sturdy landmark would last forever.

But on the morning of Dec. 26, 1889, a 72-mile-an-hour galesmote the city and the old pole was seen to sway dangerously. Firemen were called and just as they were about to secure the shaft to anearby building with ropes, they heard a sharp cracking noise andthe Liberty Pole, broken in two, fell crashing into Main Street withits tip pointing into East Avenue. No one was hurt although thetoppling pole just missed the carriage of A. M. Lindsay, the merchant.

For months the stump stood at the corner like a crippled mendicant. A movement was started for a new pole and a coin box wasplaced in the stump for donations. But no firm would make a steelpole of the heroic dimensions of the old landmark. So the idea wasabandoned and the stump removed.

An inscribed bronze plate was placed at the site in 1925 bythe Society for the Preservation of Historic Landmarks. It was putin the pavement because a city widening project had shaved off theold right angle junction of Main and Franklin streets.

One morning the marker was missing. It had been ripped fromthe pavement. No one knows what became of it-except the lawlesssouvenir hunter or mercenary miscreant that lifted it.

* * * * *

The Glen House belongs to that bygone time when the Geneseewas a sylvan stream flowing between high green banks, a thing ofbeauty and a joy to recreation-seeking Rochesterians, not just adumping ground for waste and debris.

For a quarter of a century the resort on the west bank of theriver, just north of the present Driving Park Avenue bridge, was afavorite rendezvous. Its airy dining room was noted for its excellentcuisine and its elevator in the 200-foot tower for its eccentricities.The wide verandas facing the river echoed to the shuffle of dancing

The Glen House was built in 1870 by Ellwanger & Barry,Chauncey Woodworth, the perfumer, and James Whitney, who alsopromoted the adjacent picnic grounds, known variously as Maplewood, Maple Grove and Maplewood Park.

In those days there was no Driving Park bridge. The site wasthe terminus of the Lake Avenue horse car line. Unless one wantedto drive a horse down to Charlotte-and many did-there was noalternative route save the side wheelers and screw steamers thatplied the river between the Glen House and Lake Ontario.

There were romantic moonlight excursions, more sedate "shoebox lunch" picnic cruises on the City of Rochester, the sidewheeler,which later was reconverted into the J. D. Scott; and the screwsteamers, the Wilcox and the Charlotte.

The elevator, built in 1878, was as unpredictable as the "OldCalamity" lift bridge over the canal in West Main Street. It got itspower from the nearby Lower Falls. At its top a covered runwayled to the street. Some timid folk preferred to walk the hundredsof steps to the river bank rather than trust to the vagaries ofthe lift. After the elevator dropped half of the 100 feet of its shaft,shaking up its load of school children, finis was written to its erraticcareer.

Start of electric trolley service to the lake in 1889 doomed theexcursion boats and the crowds that danced in the river breezes atthe Glen House grew steadily smaller.

But the resort held on until one May night in 1894 whenflames raced through the Glen House. Trapped in her bedroom, aMrs. McIntyre, mother-in-law of the proprietor, Jacob Valley, perished in the fire.

For six years the charred ruins remained. The fire had failed tolevel the tower and children continued to play about the siteuntil 1900 when the city fathers ordered the hazard removed.

The adjacent picnic ground, once noted for its cool Indianspring, has a history of its own. In the early days the Senecascamped there. It was a camp ground for Union volunteers in 1863.Around 1871 it housed a beer garden-but not for long. Neighborsprotested the Sabbath breaking noise and in 1872 Maplewood wasrenamed Maple Grove and for years was a tranquil picnic ground,encircled by a high board fence. In 1904 it became a link in the citypark system and the fence came down.

Now it's Maplewood Park and hundreds admire its rose gardens and walk its old trails. But from the gorge below no longerswell the haunting music of the waltz, the merry laughter of themoonlight excursionists, the whistle of the old sidewheelers. TheGlen House lives only in memories.

* * * * *

Had not Rochester long ago been incredibly short sighted, thefalls of the Genesee, in the city's heart, would not today be virtuallyinaccessible and all but hidden from the eye of man-and FallsField would have been preserved as a public park,

Now the miscellany of a junk yard litters most of what was foryears Rochester's playground on the eastern brink of the UpperFalls.

During the city's early years, thousands trooped to see whereSam Patch had leaped to death. Once New York Central through-trains halted here so that passengers might walk down a riverside promenade and view the falls of the Genesee-at five cents a head.

As early as 1847 circuses pitched their tents at Falls Field.There in 1858 De Lave walked a tight rope high above the gorgebefore 18,000 pop-eyed spectators.

Falls Field, also known as Genesee Falls Park, was boundedon the east by St. Paul Street, on the south by the Central tracks, onthe west by the river and on the north by Cataract Street.

The golden age of Falls Field was the decade that followedJohn Meinard's purchase of the amusement center in 1878. A fewremain who remember the green and shady picnic ground, thefountain, the beer garden, the restaurant that specialized in Germandishes, the menagerie, before the days of a city zoo, behind the tallfence on the St. Paul Street side; the bowling hall, the duck ponds,the swings that carried one almost over the foaming waters, theexcellent Sunday concerts-not to mention the first merry-go-roundand the first indoor ice skating rink Rochester knew.

Falls Field was the gathering place for the considerable German community of the time and the folk lore and music of the Fatherland made picturesque the fall harvest festivals held there.

Altogether it was a gay and charming play spot there besidethe falls until in the early 1890's it was dwarfed by the rise ofOntario Beach, with its new trolley link to the city.

So Falls Field went the way of the Glen House. Unsightly buildings rose around the cataract. The sooty hand of industry clutched it and the glory of Rochester's waterfalls was hidden away-to Rochester's everlasting discredit.

* * * * *

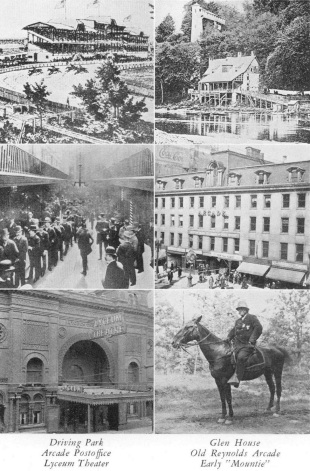

When the wreckers' axes battered at the walls of the old Reynolds Arcade in 1932, grandpa and his generation felt that a chunkwas being carved right out of old Rochester's heart.

For 103 years it had stood there, a landmark of landmarks.No other stairways had been worn down by the tread of so manyfamous feet.

When in 1828 pioneer Abelard Reynolds began his Arcade, thelargest and most expensive ($30,000) building west of the Hudson,doubting Thomases shrugged over such a grandiose project in a newtown of only 8,000 souls.

In a few months after its completion in 1829, they were proudlyshowing off to out-of-town visitors the new Arcade, one of thearchitectural marvels of America.

It really was an immense building for the era, four stories highwith a frame loft and an observatory which commanded a splendidview. It had 100 feet frontage on Buffalo (Main Street). No nailswent into its building, only hickory pins and morticed timbers.

Its distinctive feature during all its 103 years was the open central passageway or arcade under a glass roof and with a double tierof galleries, lined with shops and offices, and reached by narrow,ballustraded stairways. Once a drinking fountain stood in its center and to the last, on the north wall, a massive clock, flanked by thebusts of three generations of Reynolds men, Abelard, William andMortimer, and on the walls hung reassuring red fire buckets.

Long ago the original Arcade was extended back to CorinthianStreet, a Main Street addition was built and other changes made,notably after it was damaged by fire in 1909, but never any essential alterations made to its general plan.

Today a tall, modern office building, bearing the old name,stands on the historic spot where Abelard Reynolds in 1812 openedin his tavern-saddlery shop Rochesterville's first postoffice, a pinedesk, with 100 pigeonholes for the mail brought once a week bypost rider from Canandaigua.

But this fine new building is not the Arcade of your grandsire'snostalgic memories,

If that old Arcade could come back, what shades would hauntits corridors, thump up its ancient stairways, lean over its balconies.

We see Jonathan Child, Colonel Rochester's son-in-law, takingthe oath of office as first mayor of Rochester, a post he soon is torelinquish rather than sign licenses for the sale of intoxicatingliquor.

From the same balcony in a later day, Daniel Webster poursout perfervid oratory and there are those who think the statesmanis overly exhilarated.

We see the beginnings of culture in a raw boom town as scholars lecture the students of the Athenaeum.

Hiram Sibley and his associates mold a network of short competing telegraph lines into the mighty Western Union and for yearsthe Arcade is the telegraphic center of America and the local officesof Western Union to this day remain in the site of its birth.

Worried crowds mill around the big bulletin board to get thelatest news from Civit War battlefields and one day in 1865 recoil inhorror when word is posted of Lincoln's slaying.

Again the Arcade is thronged with men in bowler hats andcutaway coats, stopping in for their mail on Sunday mornings afterchurch. From 1833 to 1891, when it was moved to the FederalBuilding, the city postoffice was in the old Arcade.

We see a young craftsman, John Jacob Bausch, grinding lens ina tiny shop he shares with a cobbler and a huge industry is born. Apatent lawyer, George Selden, works out the problems of the internal combustion engine on a cluttered desk.

A thin lad of 14 named George Eastman goes to work at hisfirst job in an Arcade real estate office-at $3 a week.

A stocky, absent-minded youth of 22 named Thomas A. Edisonsleeps at night in the battery room of Western Union after munching on a five-cent loaf of bread which is his dinner while he triesout his new quadruplex telegraph sending device.

A country youth, Glenn Hammond Curtiss, parks his bicyclewith those of the other delivery boys on the rack outside the WesternUnion office long before an airplane droned above Keuka vineyards.

There's an artists' corner in the old Arcade and men in Byronic ties strive with brush and palette, among them such notable painters as Grove Gilbert.

Doctors, lawyers, merchants, chiefs, stock promoters, news vendors, bootblacks, organ grinders in the doorway-phantom figureshaunt the old Arcade.

* * * * *

When 43 years ago workmen began tearing down the fire-ravaged remains of the Academy of Music, people trooped down to Corinthian Street to carry away souvenirs of the old building, a brick, a piece of woodwork, anything.

The policemen on guard turned their backs indulgently. Theyknew the sentimental ties that bound the doomed playhouse toRochester hearts.

The square, high-windowed structure began in 1849 as Corinthian Hall, so named because of its general style of architecture.William A. Reynolds, son of Abelard, built it and it was a fineauditorium for its day, seating 1,200 persons. In 1878 it was reconstructed and renamed the Academy of Music. In 1898 it was swept by fire, damaged beyond repair.

Its half century of life had been a glittering one. Famous feethad walked its boards. Great names had stood out in bold letterson the posters in its lobby-such names as Jenny Lind, Adeline Patti,Ole Bull, Fanny Kemble, Booth, Forrest, Joe Jefferson.

It had heard the angry murmur of the mob that threatened theFox Sisters after their "spirit rappings." It had resounded to theoratory of Beecher, Clay, Webster, Sumner, Seward, Wendell Phillips, Evangelist Charles G. Finney, and the scholarly discourses of Emerson, Holmes and Dickens. On the same platform had appeared such diverse celebrities as the Siamese Twins, Tom Thumb; the militant cleric, T. De Witt Talmadge, and burly John C. Heenan, the pugilist.

On its site arose another Corinthian, well remembered today bycircumspect, balding business men who were gay young bucks in thegaudy days of burlesque. In time that playhouse bowed to changingcustoms and now there's only the unmelodious racket of an autoparking lot where once rang out the glorious voice of the SwedishNightingale.

* * * * *

October 8, 1888, was a red letter night on Rochester's calendar.It was opening night for the Lyceum, the last word in modern theaters. The walls were splashed with fresh paint, the gas fixtures shone and the beauty and chivalry were there, en masse.

Elegant carriages rolled up before the South Clinton Street entrance and men in full dress and hatless women in trailing gownsstepped out. They politely applauded Herbert Kelcey and GeorgiaCaygan, long forgotten names, starring in "The Wife." David Belasco and Daniel Frohman were there and congratulated the Lyceummanager, A. E. Wolff, on the brilliance of the premiere.

After 46 years, a melancholy drama was enacted at the Lyceum.The actors were the auctioneer, with his bland sing song, and thebidders, with their eager voices. The furnishings of the once elegant playhouse, now considered dingy and out of date, were goingunder the hammer. In a few days the wreckers came with theiraxes and another landmark was gone forever. There was no encorefor the Lyceum. The long arm of Hollywood had rung downthe curtain.

If its falling walls could have spoken, what a story they couldhave told of the stars that they had known. Edwin Booth, SarahBernhardt, Julia Marlowe, F. H. Sothern, Mrs. Fiske, MaudeAdams, Lillian Russell, Richard Mansfield, the Barrymores and inlater and livelier days, Harry Lauder, George M. Cohan, Thurston,Weber & Fields, Lew Dockstader, Flo Ziegfield and his Follies.

It's merely calling the roll of the stage elite of nearly 50 years.They all came to the Lyceum. For 40 years this was a "try out" townfor new plays. The playhouse was seldom dark from autumn to spring and most summers there were stock companies playing, with such budding stars, then obscure, as Bette Davis and Miriam Hopkins in their casts.

The Lyceum's final offering was the great Katherine Cornell inthe spring of 1934 in "The Barretts of Wimpole Street." You seethe Lyceum kept up its grand traditions to the last.

For hundreds of us there will always linger around a certainparking lot in Clinton Avenue memories of golden hours we spentin "The Land of Make Believe."

* * * * *

Cheer up, Grandpa, not all Rochester's ancient landmarks aredeparted.

To be sure, the old Arcade is gone, along with the Liberty Pole, the Whitcomb House, the Lyceum, the Weighlock, the Erie Station,the Warner Observatory and Rattlesnake Pete's, but. . .

The tower of the Powers Building still lifts its green and ven-erable head above the Four Corners.

Mercury, the copper god, still stands poised for flight on theskyline atop the old tobacco factory.

City Hall, "The Old Lady of Fitzhugh Street," still wears theVictorian headpiece she has all her 71 years and in that tower stillroosting among the cobwebs is the massive deep-toned city bell thatpealed out the tidings of victory and peace after four wars.

The statue of Justice, "The Lady of the Scales," still looksdown calmly on the hurrying passersby from her niche in the CourtHouse wall.

The old Free Academy of your boyhood, Grandpa, is still there,no longer a school but the nerve center of the whole city system, ona site that for 133 years has been devoted to the cause of education.

Oh, I know the landmarks are weather-beaten now, and timeworn, a bit incongruous in this streamlined, atom-conditioned age. But once they were new and splendid and the city and the menwho planned and built them were very proud of them. And theyare mellowed, not alone with time, but also with the city's historyand the memories of its people.

Sometimes a building is a sort of monument to its builder, ThePowers Building, or Block as it was long known, is a case in point.

In 1837, a fatherless, penniless farm boy of 19 came from Genesee County to Rochester seeking work. A hardware merchant took him in and for a time he worked for his board. After he received regular wages, he saved the major part of them. In 1850 Daniel W. Powers was able to open a private banking office. During the Civil War he invested heavily in government bonds, warbonds we would call them today.

Because his investment in the Union cause was sound, he beganto build in 1865 at the Four Corners, on the site of the first whiteman's dwelling on the One Hundred Acre Tract, the first fire-proofbuilding west of the Hudson.

The old Eagle Tavern went down and in its place, step by step,the enormous Powers Block rose until it was five stories high, sixon the Main-State corner. It spread out to north and west from thehistoric corners. It was a colossal project for the time, just as Abelard Reynolds' Arcade had been some 30 years before.

Into its building went four years and the best of materials andworkmanship. The wrought iron beams for its frame were importedfrom France. Artisans came from New York to lay the special facedbrick. And when it was done, the Powers Fireproof CommercialBlock was the talk of the town and the state. It had the first elevator in these parts. It was called a "vertical railway" and wasoperated by hand. At the grand opening, a proud Daniel Powers,showing off his elevator, personally hauled some of his guests upand down. Visitors gaped at the marble walls and floors, at "thegrand gaslight illumination."

But Powers was far from done, He added three more storiesand a Main Street wing in a few years. He built a tower that commanded a view of the lake on a clear day and he charged 10 centsfor that view. And in 1875 he established his Art Gallery in fourrooms of the seventh floor. The magnate went abroad collecting artobjects. He built a rotunda and a grand salon and held twice weeklyevening receptions. He installed an orchestrion, a sort of hugebarrel organ with stops. The corridors were lined with stuffed birds.Few visitors left Rochester without seeing the Powers Gallery.

Powers kept adding to the collection until it occupied at onetime 30 rooms and contained nearly 1,000 paintings and 17 piecesof statuary, with a total value of a million dollars. After his deathin 1897 the collection was sold at auction and scattered and theGallery was closed. It left a rich legacy of memories and in afteryears Thomas Thackeray Swinburne, the poet laureate of the Genesee, was to sing its wonders in this verse:

* * * * *

When in the early 1890's, Samuel Wilder began rearing a "sky-scraper" on the corner diagonally across the street, Dan Powerswatched its progress as a mother bird would watch an invasion of itsnest. The Wilder Building kept its skyward march until Sam wasable to boast that from its roof he could look down on the PowersBlock.

Powers took up the challenge. In 1892 he raised his tower so that one day his chin wisker wagged in high glee as he looked downon the chimneys of Sam Wilder's building.

There's a story that Powers once set fire to packing boxes onthe roof of his building to prove it was fire proof. The event waswidely advertised, crowds gathered, and the block withstood theflames.

In 1883 Powers fathered another ambitious project, the$650,000 Powers Fireproof Hotel, connected with his block to thewest on Main Street. It was considered the acme of elegance, withits grand dining room and giant candelabra, its brassed trimmedleather upholstery, its Hunting Room grill, its Hall of Mirrorswhere for years dancing figures were reflected and the city's sociallife revolved. Famous names adorned its registers. The Powers was"Rochester's Waldorf."

It may not merit the title today but it is still one of the Big Four of Rochester hoteldom, There's an old-fashioned homey air of plushy dignity about the Powers "Fireproof Hotel," as it nears its 65th birthday.

* * * * *

They say that Mercury is doomed; that one day the copper godthat has poised so jauntily on the Rochester skyline these 65 yearsmust descend to earth.

For when the new War Memorial goes up on the site of therambling old building, variously a tobacco factory, a collar plant andnow the City Hall Annex, on whose tall chimney the son of Jupiterhas perched so long, down will come building, chimney and all.

That will be a sad day because Mercury is more to Rochesterthan just a greenish copper statue. It is a landmark, a lodestar inthe sky. Rochester without its Mercury would be like Boston without its codfish weather vane atop the State House.

Let's go back to a gala day, that January 29 of 1881, when abrand new Mercury was unveiled and hoisted to its pedestal abovethe Genesee, amid the cheers of a shivering crowd and the strains of "Hail Columbia," played by the 54th Regiment Band.

The year before, William S. Kimball, the tobacco tycoon, hadbuilt his huge, fortress-like plant, around a courtyard, on the"island," washed by the waters of the Genesee River, the Carroll-Fitzhugh mill race and the old Erie Canal.

Kimball commissioned his talented young brother-in-law,Guernsey Mitchell, to design for his factory a statue of the god ofGreek mythology taking flight. Mitchell made a plaster model ofMercury-in a canvas-encircled, shed-studio in a yard at Park Avenue and Rowley Street.

The model was turned over to a Water Street sheet metal firmwhere the copper plates that comprised the 20-foot figure were madeand riveted together. When the Messenger of the Gods was raisedto his sentry post, 182 feet above the level of the street, he was heldin place by a copper rod. The sculptured face of Boreas, the fiercegod of the North Wind, formed the base to which the rod wasfastened.

The building changed hands several times and played variousroles, other landmarks passed on and brash newcomers thrust theirheads above him, but the copper god remains as constant as theNorth Star, an earth-bound courier ever ready for flight. Rochestercame to cherish Mercury as a tradition, a symbol and an old andfamiliar friend.

Older Rochesterians will remember the "voice" that went withthe old tobacco factory. It was a deep baritone and could be heardall over the city, four times every week day. People set their watchesby the Kimball "fog horn,"

The whistle was first blown from the earlier home of the tobacco factory on South Avenue near the canal. When it heraldedthe dawn of the centennial year of 1877, a night of celebration, featured by an exhibition run of fire apparatus at midnight, its unearthly din almost caused a panic. Unprepared and frightened citizens dashed out into the streets and were nearly run down by the firehorses. Carriage horses took fright and scores ran away. After thatthe "fog horn's" blast was toned down. But its strident voice,silenced these 40 years, and the aromatic smell of tobacco that usedto waft from the old factory are green in many a memory.

The Kimball plant, which in the middle 1880's produced a million cigarets a day and employed 1,200 hands, became a part of the American Tobacco combine. After Kimball's death, it was purchased in 1903 by the Cluett-Peabody interests for a collar factory. After 20 years that industry folded its tents and for a time the structure was vacant.

Then in 1924 because George Eastman ardently desired a CivicCenter over the river and sought to squelch a move for a new CityHall on Broad Street, he bought the deserted factory and leased itto the city for a nominal sum for office use. The University of Rochester, Eastman's beneficiary, has continued the arrangement with thecity.

I reckon Rochester can get along without the old building butMercury MUST have a place somewhere against the Rochester sky.

* * * * *

One hundred and thirty.three years ago the pioneers of Roch.esterville erected on a lot in South Fitzhugh Street set aside for thatpurpose by the proprietors of the village, a one-story frame school-house, 18 by 24 feet. Before the builders arrived, Silas O. Smithharvested a crop of wheat between the stumps on the newly clearedsite on the edge of the forest.

The first school had a fireplace at one end and on three sidesan inclined shelf nailed to the wall served as desk space for thepupils, who sat on long benches without backs, facing the wall untilthey were called on to recite.

That primitive temple of learning served until 1836 when a larger stone building replaced it. In 1874 a fine new Free Academywas erected. It was the city's only high school until 1903 when EastHigh was built. West High came into being a year later. The oldAcademy is enshrined in the memories of thousands of Rochesterians who were part of the army of book-laden boys and girls thatstormed through its halls.

It's still there after 72 years. They call it the Education Building now and it's the headquarters of the city's vast public schoolsystem.

Thirteen South Fitzhugh Street is truly a historic spot-for 133years of "book learning" is a long, long time.

* * * * *

Rochester has another educational landmark to which few payany heed nowadays.

It is the four-story red brick block on the north side of WestMain Street just east of the Clarissa street intersection. It houses arow of little stores-a "hot" stand, a cigar store, a "trick souvenir" shop, a lunch room. There's nothing to distinguish it from other old buildings in that rather frayed section of town-unless you happento notice the inconspicuous metal plate in the center of the secondstory front wall. That marker proclaims that "here the Universityof Rochester began its life in 1850 and remained until 1861."

The building is 128 years old. First it was the United StatesHotel hard by the Clinton Ditch. Then for a time it was a girls'seminary. In 1832 it became the terminus of Rochester's first railline, the Tonawanda Road, that linked this city with Batavia.

In 1820 the Baptists of the state had established a theologicalschool, Madison University, at Hamilton. It admitted other thancandidates for the ministry and a movement began as early as 1830among Western New York Baptists for removal of the school toRochester.

The removal plan met with stout resistance and failed but nevertheless its proponents went ahead and the University of Rochesterwas chartered in 1850 and five professors and some of their studentscame to the new college from Hamilton. There's a whimsical observation, attributed both to Ralph Waldo Emerson and to OliverWendell Holmes, regarding the University's beginning:

"A landlord had an old hotel he thought he would rent for aUniversity, so he put in a few books, sent for a coach load of professors, bought some apparatus and by the time green peas were ripe, graduated a large class."

Certainly the new college prospered. The theological seminarywhich eventually became the Colgate-Rochester Divinity Schoolthrough merger with the older school at Hamilton, started simultaneously with the University and used the same building at firstalthough each retained its identity.

The rest of the story is familiar history-the removal of theUniversity in 1861 to eight acres of land "way out in the country,"donated by Azariah Boody. That's the present Prince Street Campusof the College for Women. Prince Street was named, not after ascion of royalty, but for Boody's horse, or as another version has it,his pet dog.

Visit the two campuses of the University today, see the mellow,dignified, tree-shaded older one with its blend of Victorian and20th century architecture, and the magnificent modern plant of theMen's College "beside the Genesee," and it's hard to believe theysprang from a dingy old former hotel beside the Clinton Ditch.

* * * * *

Some of our public buildings have been with us a long time.Too long, did I hear you say? Still they're in the landmark department and how we'd miss any one of those old timers.

For example, the "dean" of the lot, the County Penitentiaryout South Avenue. It is 92 years old and was built in the administration of Franklin Pierce.

Convention Hall, built as an arsenal, is in its 77th year. It haswelcomed presidents, political bosses, great musicians, lecturers,evangelists, conventions, boxing bouts, dog shows, flower shows,welfare clients.

City Hall, "The Old Lady of Fitzhugh Street," will never see72 again. She was once a proud belle for when she began life in1847, she was called "the finest municipal building upstate," Thebell in her tower is even older. It was moulded in 1851 and beforethe City Hall was built, it hung in the second Court House.

That Court House with its stately dome gave way to the presentbuilding 52 years ago. But the statue of Justice in its Main Streetwall goes back to 1850 when a wandering French craftsman carved"The Lady of the Scales" out of pine wood. Justice is traditionallyblind but the artist was so pleased with the features he had carvedhe could not bear to bandage her eyes.

The Federal Building in Church Street is no spring chicken. Itwent up in 1884. It's a year older than the County Jail. PoliceHeadquarters is "only" 51 years old.

The total age of these seven principal public buildings is 465years.

To next chapter

![]() To GenWeb of Monroe Co. page.

To GenWeb of Monroe Co. page.