Salt of the Earth

Salt of the EarthGOING to Warsaw on my "Stage Coach-Motor Bus" tour was sort of like "going home."

For I was born in that hill country, only 20 miles to the southwest in Cattaraugus County just over the Wyoming line. But in my boyhood I seldom got to Warsaw. Twenty miles was a long, long way in horse and buggy days. In later years when occasionally I rode the night train on the old B. R. & P. I would always look for the friendly lights of the village twinkling down in the valley so far below the lofty East Hill on which the station roosts.

The shire town of Wyoming County lies picturesquely between two great ridges. On each perches a railroad line. The Erie is on the West Hill.

I found Warsaw much as I had remembered it, It well kept, well shaded village with an air of stability about it. It is a sure-footed sort of town and looks before it leaps. It is not given to heroics or aggrandizement. After all, it was settled by Yankees. Warsaw is a friendly village with that quiet friendliness that is genuine and lasting.

This county seat town that bears the name of an Old World capital has always sailed on a pretty even keel. Its population has hovered around the 3,500 mark these 25 years. Its only boom—and it was a robust one—came around 1880 when a rich bed of salt was tapped in the region and Warsaw waxed into the center of the salt industry that flourished in Western New York for two decades.

* * * *

Warsaw's first settler must have implanted into the town he fathered something of his own practical, determined spirit. He was Elizur Webster and he came to the Holland Purchase from Washington County in 1803 when there were few settlements west of the Genesee. He looked over the lands that Surveyor-Land Agent Joseph. Ellicott had cut into township squares and picked the one that became Warsaw. He wanted to settle in its exact center so he made a measuring line of basswood bark and with a compass determined the central point—with remarkable accuracy as later surveys showed.

Asked to make an official survey, Ellicott demurred, urging Webster to buy lands already surveyed. Most of the pioneers who came to the Land Office at Batavia had only an ax and a gun. Elizur Webster had $1,000 cash in his pocket. When Ellicott learned that, he changed his tune, ordered the survey and sold to Webster 3,000 choice acres along the Oatka (then Allen's Creek) at a bargain rate of $1.50 an acre. The pioneer later sold most of them to settlers at a neat profit.

He raised his cabin in the lonely forest, aided by choppers who were clearing the way for the Buffalo-Geneseo Road. He built the first saw mill and opened the first tavern. He became a man of consequence in the new community.

When Warsaw became a township in 1808, Elizur Webster was named its first supervisor. The present supervisor, Clayton O. Gallet, is his great-grandson.

To the Red Men Wyoming County with its formidable hills was a land of passage rather than that of settlement although remains of two early Indian villages have been found near the headwaters of the Oatka east of Warsaw.

Warsaw grew into a trading center on the frontier and a stop on the stage coach line to Buffalo. The coach horn, sounded on the East Hill, echoed over the valley to tell the postmaster and the innkeeper of the mail stage's approach.

Warsaw grew into a trading center on the frontier and a stop on the stage coach line to Buffalo. The coach horn, sounded on the East Hill, echoed over the valley to tell the postmaster and the innkeeper of the mail stage's approach.

* * * *

Warsaw is a citadel of the Grand Old Party in one of Upstate's scaunc_hest Republican counties. Indirectly it played a part in the birth of the GOP.

On November 15, 1839, a group of anti-slavery zealots, meeting in Warsaw's Presbyterian Church, put into the field the first national ticket of the Liberty Party, with James G. Birney, a former slaveholder, as its standard bearer. The convention was attended by only 50 delegates because of the wretched roads, but it had considerable national significance. The Liberty Party dramatized the slavery issue which eventually gave rise to the Republican Party—and brought on the Civil War.

Warsaw was a hotbed of abolitionism although the majority of its citizens were moderates. It was a station on the Underground Railway and in the home of Deacon Seth Gates, now the residence of Arthur Wares in Genesee Street, was a secret cellar in which were hidden fugitive staves bound for Canada and freedom.

Deacon Gates had a son, Seth M., who became a member of Congress and opposed the extension of slavery into free territory with such vigor and eloquence that a certain wealthy Georgia planter offered $500 "for the delivery of Seth Gates in Savannah, dead or alive."

Congressman Gates lived in the rambling white house with the green blinds on Perry Avenue that was built in 1825 and is now the home of the Warsaw Historical Society.

In 1848, so the story goes, an Abolitionist in Washington, told by a female slave that she was to he sold "down river" and separated from her 7-year-old son, put her and the boy into a large box that just fitted in the back of his market wagon. He bored holes in its side for ventilation, put in a jug of water and a supply of food and drove off through Maryland, over the Pennsylvania mountains, following the North Star, until on the 22d day he reached his destination, the Warsaw home of Isaac Phelps. There the woman and boy were freed from their coffin-like hiding place, little the worse for the long ride. Both became respected residents of Wyoming County.

* * * *

When Wyoming County was formed from Genesee in 1841, Warsaw won the county seat over the spirited rivalry of East Orangeville and Wethersfield Springs, now mere hamlets. In 1878, Warsaw fought down a move to transfer the county seat to East Gainesville, now Silver Springs.

The most exciting days the Wyoming Valley ever knew followed the accidental discovery by oil drillers of a rich vein of salt in the town of Middlebury. The oil men shifted to the production of salt and began pumping out the brine from the well. At first it was placed in open vats to be evaporated by the rays of the sun. Portable roofs protected the vats from the rains. Then a plant was built for boiling out the brine.

Crowds came from far and near. It was like a gold rush. Warsaw caught "the salt fever" and in 1881 the first well was drilled in the town on the Keeney farm. As Mrs. Margaret Smallwood, daughter of Dr. W. C. Guoinlock, a salt manufacturer, recently wrote for the Historical Society, "low lying buildings, accented by derricks, chimneys and tanks sprang up like mushrooms all along the Erie and BR&P tracks."

Operators flocked in from other fields. At one time there were eight salt works in the town. The salt wells were pumping day and night, the barrel factories were booming and a new occupation dawned for the women and girls of Warsaw, filling and sewing small, dairy salt bags. It was like "playing in a warm snowy sand pile." Real estate values rose, new houses went up and the population of Warsaw gained 1,200 in the 1880's. Salt was king and boom town Warsaw was the capital of the saline realm.

Local interests went heavily into the salt business, notably the Humphreys, a family potent in the financial and political affairs of the county for 75 years. The salt industry had its woes. Brine tanks burst, smoke stacks blew down, fires swept the plants, workmen were scalded when they slipped into the boiling vats.

For two decades the wells pumped away along the tracks. Warsaw salt was prized for curing meats and butter making. Long salt-laden trains rolled over the parallel ridges. But the salt operators overplayed their hand. The salt bed did not give out nor did the salt lose its savor. It was a case of overproduction. Also the Warsaw field was deficient in water supply and in cheap transportation by waterway. New fields were developed in Kansas and Michigan. So there came a time when the sidings at Warsaw were clogged with cars of salt with no place to go.

In 1899 a ten-million-dollar combine took over nearly all the salt properties in the region, then sold them to the International which closed down the plants, one by one. The big works at Rock Glen lingered until the late 1820's [sic.; probably should be 1920's].

Today the brisk village of Silver Springs is the last stand of a once mighty industry. It was there that Joseph Duncan instituted a revolutionary vacuum process of salt evaporation. The Worcester plant in Silver Springs is a booming industry and the economy of the village revolves about the big salt works.

When the combine bought the Warsaw salt plants, much of the money went into new local industries, most of which are still going today. Warsaw produces elevators, buttons, textiles, lanterns and road flares. Once the village had an organ factory, which was doomed by the advent of sound movies.

The rise and fall of the salt empire now is history. But tales of the boom days persist, like the one about an ace driller named Tom Percy. After drilling most of the Warsaw wells, he moved to Michigan. When a drill at one of the Warsaw plants got stuck, a Macedonian message was flashed to Tom Percy. He came with his men and they retrieved the drill in short order.

Tom presented his bill: "To fishing; up one set of drills, $1000."

The plant owners thought it excessive and asked for an itemized account. Here is what they got:

"To fishing up one set of drills ----------------------------------------- $ 25 To knowing how ----------------------------------------------------------- $975

The bill was paid.

* * * *

Everybody told me "You must see our village park." Warsaw is justly proud of that 22-acre park on the old fair grounds where the Wyoming County Agricultural Society held fairs for nearly 70 years. The village bought the grounds in 1925. The development of the park was really born of the great depression. Warsaw was quick to grasp its share of relief funds. Workmen on relief graded the park, mostly with picks, shovels and wheelbarrows, for the rules of the federal agency forbade use of machinery. Sometimes they worked with the mercury at 40 below in that record winter of 1932.

Today the village park houses a $37,000 swimming pool and bathhouse, a memorial to former Mayor Nathan S. Beardslee, who left $23,000 for its construction; macadam tennis courts, football and baseball fields, a large Veterans' Memorial Building for American Legion and other gatherings, Boy and Girl Scout cabins, picnic shelters, benches, a wading pool. I doubt if any other village of Warsaw's size has so fine a recreation park. Relics of the old County Fair days are the big grandstand and the half-mile track.

Chuckles punctuated a tale of the park project. When the slate TERA was running the relief show, village officials telegraphed to Albany a request for $6,000 for park development. Either through an error in transmission or some bureaucrat's inability to conlprehend sums under five flgures, the village fathers the next day were nonplussed to receive a wire stating that their request for "$60.000 for park purposes" had been granted. Then they considered the matter in the realistic Warsaw way. About all the locality had to provide was the labor. So they went ahead on the $60,000 basis.

* * * *

The first man I met in Warsaw was Levi A. Cass, alert and natty 84-year-old retired publisher of the Western New Yorker and six other yoming County weeklies. He took me on a tour of the village, driving his own car.

Cass looked back over his 45 years in the county seat village. He talked about old political battles for he was a power in politics. His eyes shone brightest when he told about the things he and his associates, most of them now gone, had "done for Warsaw." There was the successful campaign to get the BR&P to build a freight house in the valley and to lay its tracks down to the business section from the hill. It means a lot to the village. Cass particular pride is the Wyoming County Community Hospital. The publisher came to Warsaw in 1902 and within two years he began a campaign for a hospital.

The present 122 bed hospital on the banks of the Oatka is said to be the largest in the nation serving a county of Wyoming's population rank. It began in 1911 as a private residence. Its founder was Dr. W. B. Thompson who had been a successful surgeon in New York. His aim was to provide a rural community with the same type of specialized service as given) by any city hospital—with the co-operation of the physicians of the region.

After being taken on a tour of the hospital by affable, youngish Director Warne A. Copeland, I felt convinced that goal had been attained.

The hospital was taken over by Wyoming County in 1930 and operating with state aid, has expanded gradually into the present modern plant. It serves Livingston and other nearby counties, as well as Wyoming, and is a major village "industry," with its staff of 140 employes.

There's a 90-foot waterfall on the Crystal Brook, Warsaw Falls, but a salt plant long ago killed the trees and grass around it and ruined it as a picnic spot. Besides, the three magnificent falls of Letchworth Park are right in Warsaw's backyard.

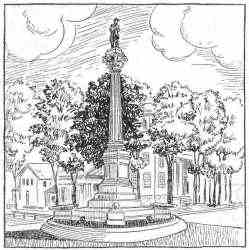

A landmark is the tall Soldiers' Monument near the county buildings, a Corinthian column surmounted by the heroic figure of a Union soldier, his musket "at rest." The shaft, which was part of the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in 1876, was erected later that year after a strenuous county-wide fund-raising campaign. Its formal dedication was neglected until the centennial of Warsaw's settlement in 1903.

Once Warsaw had a famous Nyack Band that played at the first Chicago World's Fair, at Coney Island, at the Toronto Fair and at the Thousand Islands and that was invited to the Paris Exposition. Nov it has a lively unit of the Society for the Preservation of Barber Shop Singing in America, of which a local manufacturer, Phil Embury, once was international president.

Warsaw folks have a deep and quiet price in their village. Historically-minded Lewis H. Bishop, the veteran village clerk, former Mayor John H. Moore and others I met in the Village Building, all sounded that same note.

And from way across the continent, from Los Angeles, Earl A. Brininstool, a native son who went West in the later 1890's and achieved renown as a writer (See Who's Who). sent me a batch of clippings. They were reminiscences of his boyhood in Warsaw

. . . of the glorious fishing and swimming in the Oatka and the Crystal Brook before the salt plants polluted the waters . . . of the Irving Opera House and the medicine shows . . . of the last execution in Wyoming County in 1889 when from a gallows in the jail yard dangled the body of "Happy Bob" Van Brunt, a Salvation Army lad who had killed a Castile youth over a girl . . . Of the Letchworth Rifles, the local militia, at target practice in "The Gulf" near Warsaw Falls . . . of the old reap roller factory at South Warsaw . . . of dances and sleigh rides and boyish pranks and the tender grace of a day that is dead.

* * * *

Warsaw is in the heart of a dairying and potato growing region. Once maple sugar was a major product but fewer maples are tapped each passing year.

To the southward is Gainesville, 1,616 feet above tidewater, which is a little higher than Saranac Lake in the Adirondacks and where huge crops of potatoes are raised. There a famous American also was raised. He was Dr. David Starr Jordan who as a boy gathered natural specimens on his father's farm before he became a leader in science, a crusader for world peace and the president of Leland Stanford University. Belva Lockwood, the only woman ever to run for the Presidency, once was principal of the old Gainesville Female Academy.

At Wethersfield Springs, now only a crossroads hamlet, also was a well known school, Doolittle Institute, founded in 1860. The main building of the Episcopal school still stands. So does the low frame former tavern that was built in 1830 with its ballroom with the spring floor. It's a private residence now and gone is the bar of solid cherry.

In the Town of Wethersfield is another hamlet, named Hermitage after the Tennessee retreat of Andrew Jackson. It was settled in 1809 and a king pin along its pioneers was Lewis Blodgett. He became wealthy and married an heiress. To them a son, James L., was born in 1822.

After graduating with honors from Yale and teaching mathematics at his Alma Mater for a time, James Blodgett returned to his native village to look after his father's manifold interests. He was betrothed to a local belle and began building a fine residence for her. But after lie chanced to overhear her tell a girl friend that she was marrying him for his money, he broke the engagement, and left untouched during, the rest of his long lifetime the home he had been building for his bride. After that no woman save his mother ever crossed his threshold and James Blodgett was a changed man.

He became an almost fabulous eccentric, "The Hermit of Hermitage." Reputedly a millionaire, a private banker, owner of many farms and mortgages and some Rochester and Buffalo business property, he dressed in greasy work clothes that any penniless farm hand would have scorned. He lived alone, cooked his own meals, made his own shirts. He either walked or caught rides when isiting his properties. Stingy in most natters, he was given to fits of generosity. And his word always was good.

As the Blodgett fortune mounted, so did the legends about him. Four times he was the victim of robbers, lured to quiet Hermitage by the tales of his hidden gold. Twice the bandits heat him cruelly when he was an old man.

On a bitter winters night in 1905 his lonely home caught fire and he perished in the ruins. The next morning men burned their hands snatching at the gold pieces in the ashes—even before they bothered to look for the body of "The Hermit of Hermitage."

So passed into folklore James Lewis Blodgett, the rural Croesus, the Yale graduate who looked like a tramp.

COMMODORE Oliver Hazard Perry, the naval hero of the War of 1812, had a lot of pep. He was a self reliant, independent chap and obstacles never daunted him.

Before he trounced the British in the Battle of Lane Erie, he had to build his own fleet, a long, tough job. Only two years before, he had faced a naval court of inquiry for loss of his ship and had fought his way up from that ignominy. He was a man of deeds, not words. Every history book records his laconic report of one or the most brilliant victories in the annals of American warfare: "We have met the enemy and they are ours."

The Wyoming County village they named after the doughty Commodore has much of his resolute, independent spirit. Perry, N. Y., lively mill town of some 5,000 souls, has a way of getting things done—usually by doing them herself. She stands on her own two feet. She is not bound by precedent. And when it comes to a community undertaking, the men and women of Perry close ranks.

Way back in 1838 after a principal industry, a foundry, burned, everybody turned out for a mammoth building "bee." The farmers hauled the cobblestones in their wagons, the masons and the carpenters did the labor and soon the stone factory rose that is still on Main Street, part of the Robeson cutlery plant.

Tired of long years of being an inland town, dependent on stage lines, the men of Perry in 1872 built their own railroad, a spur line to connect with the Erie at Silver Springs.

When the village felt the need of a good hotel, the $100,000 Commodore was built in 1925 by popular subscription. Seven years later it was sold at forced auction and the subscribers took their licking like good sports. After all, Perry had its fine hotel.

During the depression of the 1930's when other communities were grabbing avidly at the federal largess, free and independent Perry voted down PWA aid, setting a precedent in the area. It floated its own $100,000 bond issue for public works.

* * * *

Permanent settlement in the town goes back to 1807 when Samuel Gates raised a cabin on a hill overlooking the shimmering waters of Silver Lake. He and most of the other pioneers were of the rock-ribbed New England stock. During the "Black Freeze" of 1816-17 when there was a frost every summer night and the crops froze in the fields, game from the woods and fish from the lake kept the settlers alive.

Perry had several names before it was rechristened in honor of the hero of Lake Erie. They were Slabtown, Shacksburg, Beechville, Columbia and Nineveh.

During the second decade of the 19th Century, a Perry man, Hugh Higgins, solved his personal housing problem. He burrowed a cave in a hillside near the present railroad curve, put up flat stones at the front, leaving apertures for a door and a window and in that dugout reared a family of eight.

The frontier knew no more gallant figure than Dr. Jabez Ward, who practiced at Perry Center. He rode his horse over the rough roads until both horse and rider would nap and sometimes the doctor would fall from his mount in sheer fatigue. Often he would follow the light of a torch in the hand of a settler guiding him to some lonely cabin in the woods. When his slim stock of medicines gave out, he went out and gathered bark, herbs and roots.

There came a time when the doctor, old and tired, was stricken with pneumonia. Two young friends were sitting up with him to administer medicine at regular intervals. Toward dawn the watchers nipped. There came a faint knocking at the door. The watchers slept on. But the old doctor, his ear attuned to such noises, heard. He dragged himself to the door. There stood a man with an urgent call from a patient miles away. The doctor dressed, got out without waking his attendants and rode away to his patient. He returned without his friends knowing he had left. Then he lapsed into delerium. The next day Dr. Jabez Ward died, a martyr to his professional duty. That was in 1843. He sleeps in the old Prospect Hill Cemetery at Perry Center.

Perry Center on its northern hill was an early rival of Perry Village but long ago gave up the race. For the village on the Silver Lake Outlet grew like Topsy, without particular plan, as its street layout shows today. It became a trading center and a stop for the stage coaches on the old Allegany Road from Canandaigua to Olean. There were other stage lines, to Mount Morris, to Batavia, and other points. Perry remained a stage coach town longer than most because the railroads and the canals bypassed it.

After local capital built the Silver Lake Railway in 1872 to link the village with the Erie, it no longer was an inland town. Ten years later a spur was built from the B,R&P at Silver Lake Junction and Perry really began to hum. It gained more population in two years than in the previous two decades.

The Silver Lake Outlet powered the first saw and grist mills. Where the outlet joins the Genesee, the saw mill that Ebenezer (Indian) Allen, the bigamous pioneer of Rochester, built in 1792 supplied the first boards used in the region. There flourished the one time industrial center of Gibsonville, now a "ghost town."

The Silver Lake Outlet powered the first saw and grist mills. Where the outlet joins the Genesee, the saw mill that Ebenezer (Indian) Allen, the bigamous pioneer of Rochester, built in 1792 supplied the first boards used in the region. There flourished the one time industrial center of Gibsonville, now a "ghost town."

For years Perry had large flour mills. It shared in the regional salt boom of the 1880's and 90's and its salt works lasted until 1909.

The village's major industry, the Perry Knitting Mills, was founded by local interests in 1881. It employs some 1,000 hands from all over the area. Other industries are the expanding Robeson cutlery plant which came to Perry in 1896 and was founded by Millard F. Robeson, a onetime "drummer" who sold pocket knives as a side line; the Rayotex Knitting Mills, the Duracraft Company, makers of pennants, emblems and knit goods and the Klaustine factory, which produces tanks and metal fabrications.

The mills brought a considerable Polish population, thrifty, hard working people who have been assimilated in this democratic town settled by Yankees.

In 1937, as part of a nationwide drive to unionize the textile industry, some city laborites came to town and began to organize the workers in the Perry Knitting Mills. They signed up a minority and a strike was called. While 120 pickets were in line, some 1,000 others were working in the mills.

After several days of turmoil in the usually peaceful village, a truck load of men suddenly appeared near the picket lines. They carried pitchforks—with sharp tines. Grimly, quietly, they ordered the out-of-town strike leaders to "get out." They escorted one of them to the village limits at pitchfork point, told him to get in his car and leave Perry—which he did.

The affair caused a sensation. The police guards on duty at the time said they were "too much taken by surprise" to interfere. No one was able to identify the men with the pitchforks. Union headquarters called upon the governor to investigate the "intimidation." The day after the fracas 1,000 workers staged a "loyalty parade." There were no more incidents. Perry does not like outside interference in its affairs.

* * * *

In Elm Street just off Main stands an old-fashioned white house. A curly haired boy of 3 came there to live in 1833. For four years it was his home. His father was the Baptist minister. The boy's name was Chester Alan Arthur and he became the 21st president of the United States.

Another minister's son lived in Perry as a boy and went to school there. Earl Rogers became one of the foremost criminal lawyers of his time. They called him "The Clarence Darrow of the Pacific Coast." As defense counsel in the San Francisco municipal graft trials, he was pitted against such courtroom gladiators as Hiram Johnson and Francis J. Heney, who incidentally was born in Lima, N. Y. Rogers prosecuted the McNamaras in the famous Los Angeles Times dynamiting case and crossed swords with Darrow for the defense. He was a pal of Jack London and went on sprees with the madcap writer. They found Earl Rogers' body in a squalid room in Los Angeles in 1922. He had gone far on the downhill path.

As this is written, Perry is in a sense the "summer capital" of the Empire State, A Perry man, Lieutenant Governor Joe R. Hanley, is acting chief executive in the absence from the state of Governor Dewey. Versatile Iowa-born Joe Hanley, clergyman, attorney, Chautauqua speaker, veteran of the Spanish-American and first World Wars, came to Perry in 1923 as minister of the Presbyterian Church. He liked the village and stayed there after leaving the pulpit. He went into politics and was elected to the Assembly, to the State Senate and to the office of lieutenant governor. Perry is proud and fond of its best known citizen.

A distinguished artist, Prof. Lernuel M. Wiles, was a native of Perry. For some years he conducted a summer art school on the west side of Silver Lake. He became a member of the faculty of Ingham University at Le Roy and of Nashville (Tenn.) University. In the Perry library building is the Wiles-Stowell Art Museum, full of the Wiles paintings. The collection was the gift of a former resident, Dr. Charles H. Stowell, a physician who made a fortune in Proprietary medicines. Many of the Wiles paintings are of familiar scenes around Silver Lake, such as the lay, the boat landing, an old stone quarry and a glen on the farm where the artist lived as a boy.

On the lawn of the library is a unique war memorial, 11 neat white crosses, each in memory of a Perry boy who never came back front the first World War.

* * * *

Back in 1915 when Fred Stone was "wowing them" on Broadway in the show, "Chin Chin," and long before Edgar Bergen was known to fame, a tiny man used to perch on Fred's knee and the pair did a "Charlie McCarthy" act, The little chap's stage name was Eddie Phelps and Stone would reply to his wisecracks with "Very good, Eddie." "Fddie's" real name is Gaylord Phelps and he lives, with his wife, a former wardrobe mistress in one of his shows, on a farm west of Silver Lake. Nov 60 years old., he weighs about 38 pounds and is less than 4 feet tall. He cuts quite a figure in Perry parades. Phelps was 18 years in show business. He played junior roles with Elsie Janis and with the dancing Castles. He was a featured player in musical comedy with Marion Davies in pre-Hollywood days.

A familiar scene on the streets of Perry is sightless Tommy Stevens, clashing around with his Seeing Eye dog. For years Tommy was a telegraph messenger. Now he sells from house to house. He answers by name all who greet him. He knows the voices. The townspeople are fond of Tommy and remember him with gifts at Christmas time.

The date lime "Perry. N. Y." prefaced a series of fantastic "tall tales" that appeared in newspapers all over the land in the 1920's and '30's. Thousands chuckled over them. They were the brain children of the late Guy Comfort, editor of the Perry Herald, and his assistant. Gordon McGuire. Some of them were dandies.

There was the one about Herman Strutter who lived near the beaver colony and who had a wooden leg. Herman woke up one morning to find his bedroom floor littered with chips and his peg leg missing. He figured a beaver had lugged it off and trailed the thief to the beaver dam, but he never got his leg back.

A Sucker Brook man, gathering sap, found only pure whisky in the bucket. It had leaked into the trunk from a bottle, left in the crotch of the maple tree and smashed by a windstorm. And there was the farmer whose left leg was six inches shorter than his right one because all his life he had been plowing, harrowing and harvesting on a side hill.

Another Perry yarn that hit the front pages was about the Boston bulldog with the red tinted toe nails. It came out at the time the painted finger-nail fad began.

The Herald once promoted a "Pied Piper of the Air," to rout some unwanted sparrows from a grove. An airplane swooped low over the trees and the pilot played a flute while his companion dropped salt on the birds' tails.

These "tall tales" are in keeping with the hearty personality of Perry, a town that likes to laugh.

Among my pleasant memories are my chats with Frank D. Roberts, the druggist, an authority on local lore and author of a comprehensive history of the town; with affable C. Read Clarke, publisher of the Perry Record, who knows his native village fore and aft, and with young Joe Pascoe of The Herald, a newcomer but imbued with the true Perry vigor.

I landed in Perry via Geneseo aboard a bus that rocked and jolted up and down the hills like an oldtime stage coach in the ruts. I spent a day and a night in the village. It rained every minute—and hard. Yet no deluge can dampen the blithe, infectious spirit of this mill town among and on the rolling hills of the Genesee Country.

* * * *

The 3½ miles of shining water that is Silver Lake, at Perry's southwestern doorstep, was the Senecas' happy fishing ground. According to tradition, it was to a small Indian village on the lake that Mary Jemison, the fabulous "White Woman of the Genesee," fled. from Little Beard's Town (Cuylerville) when Sullivan's avenging Revolutionary Army scourged the Genesee Valley in 1779.

Silver Lake is one-half to three-quarters of a mile wide. Its outlet and inlet, both on the north end, are only 100 yards apart. It's a sparkling gem of a lake and rich in legend and in ]ore.

Ninety-two years ago, the fierce white light of national publicity beat upon the little lake in the Wyoming hills. On the night of June 13, 1855, five fishermen of the community set out on the moonlit waters in a rowboat. Within an hour they were rowing frantically back to shore, pop-eyed and white of face. They told of seeing a great reptile, 80 feet long, with bright red eyes and a mighty lashing tail. As they gazed, the creature's mouth squirted water 4 feet in the air. The fishermen were temperate, solid men and their tale was believed.

The story of the sea serpent spread. Others saw the monster. The news wires carried the story and the people began flocking in. Soon every hotel and boarding house was filled. Citizens formed a vigilance committee and laid futile plans to capture the reptile. The countryside was flooded with fantastic rumors.

Then when the excitement was at its peak, the creature vanished. Before long the resort was restored to its wonted calm but still the mystery of the great snake remained.

Two years later, fire swept the Walker House, Perry's leading hostelry. Firemen, trying to salvage property from the attic, came upon a strange thing. It was a huge strip of canvas, made into the shape of a serpent and painted a dull green with yellow spots, with eyes and mouth of flaming red, set in a head 15 inches in diameter.

The story of a tremendous hoax came out. It seems A. B. Walker, an enterprising hotel keeper, wishing to drum up summer business, had, with the aid of friends sworn to secrecy, built the Sea Serpent of Silver Lake, which was manipulated from a hiding place on shore by means of a length of pipe, some hose, a bellows and ropes.

* * * *

The Silver Lake Assembly grounds, for a quarter of a century another Chautauqua, grew out of Methodist camp meeting grounds on the western shore.

It was a tent colony at first. Then imposing buildings arose—an auditorium that seated 5,000 people; a Hall of Philosophy, Epworth Hall and Hoag Memorial Art Gallery. The Methodists planned on a grand scale. They brought to the Assembly grounds each summer the cream of the nation's oratorical, literary and musical talent. Theodore Roosevelt when governor of New York spoke there. Other famous voices heard in the big auditorium were those of Frances E. Willard and the Rev. T. DeWitt Talmadge.

Silver Lake met its rival, Chautauqua, on the baseball diamond for it had an excellent semi-professional team. It had a quarter mile track for runners (not of the equine variety); a 40-piece band and a 40-piece orchestra. There were tiered seats for concert-goers along the lake front. From a tower a cluster of bells pealed out over the countryside during the six weeks of the summer session.

The Assembly set its sights too high. Its program was too granliose. The talent it brought to Silver Lake was costly. In its last year of operation, 1898, the program cost $40,000.

The years since have wrought changes on the old Assembly Grounds. The Methodists maintain a summer training school and an Epworth League camp there. The big auditorium burned 25 years ago. The Hall of Philosophy was remodeled into a sanitarium and then for 2 or 3 years it housed the Silver Lake Military Institute. Now its the Epworth Inn for summer students. Old Epworth Hall is used for religious meetings.

At what residents call "the lower" or "the Walker grounds," because of the hotel and dance hall which were built there on the site of an old temperance camp, there blossomed a well known amusement resort.

In the days of peek-a-boo shirt waists and shoe box lunches, long excursion trains rolled to the lakeside from Rochester, Buffalo and other points. Passenger steamboats churned the blue waters. First of the fleet was the Nellie Palmer, a side-wheeler, built in the Perry tradition by popular subscription and named after the granddaughter of a principal subscriber. It burned at its dock years ago. Old timers will remember the others, the three-decker Shiloh, the Minnehaha, the Arrow, the Queen City, and the last to ply the lake, the Gypsy, which was dismantled in 1905.

Silver Lake is the home of the Pioneer Picnic which began as an old folks' outing in 1874 under the aegis of the Wyoming Historical and Pioneer Association. In 1878 a log cabin, a faithful reproduction of a pioneer home, was built on the lower grounds to house the relics of other days. The cabin is still there but most of the collection has been moved to the nearby Letchworth Park museum.

Once the Pioneer Picnic was the big event of the countryside. Five thousand people was considered a small attendance. Notable speakers, among them Franklin D. Roosevelt, when he was governor of New York, addressed the throngs in the auditorium. That big hall went the way of the one on the Assembly Grounds, a victim of flames 17 years ago. The Pioneer Picnic is still held every year but not on the old time scale.

Silver Lake was a meeting place for the veterans of the Grand Army in their days of glory. And in winters there was the ice harvest when many hands were needed to fill the huge ice houses, now vainished from the scene. Once the yellow wagons, with the legend "Silver Lake Ice" on them, were familiar sights on the streets of Rochester and Buffalo.

The sparkling lake in the hills is still a popular summer rendezvous. Its green shores are lined with summer cottages and camps. There's a sober bustle about the old Methodist Assembly Grounds, There's the sound of revelry by night at Walker's. The Country Club on the west shore is a mecca for the golfers of the countryside and a center of social life.

Across the silvery waters come echoes of the long ago . . . the startled cries of the fishermen beholding the Sea Serpent rising out of the depths . . . the falsetto vehemence of "Teddy" and the dulcet tones of his kinsman, FDR . . . the murmur of the picnic crowds, the blare of the bands, the splash of an old side wheeler on a moonlight night and the shrill whistle of the long excursion trains.

" I WILL lift up mine eyes unto the hills . . ."

Lift up your eyes from the sidewalks of Dansville and you will see towering, even above a four-story building, a great hill outlined against the sky, 1,000 feet above the town.

On three sides this southern Livingston County village, nestling in a spur of the Genesee Valley, is surrounded by hills sip mighty that in any other region they'd be called mountains.

In this dramatic setting of skyscraper hills, dramatic history has been made.

From the lordly ridges blazed the signal fires of the Indians when all this land was theirs. On the eastern heights two rival tribes once clashed in battle.

Over the hills from the southeast came the first white settlers and they marveled at the magnificence of the primeval vista before they set to work with ax and plow.

Out of a hillside spurted an "All Healing Spring" and a health resort was born there that became known the world over. A famous woman came to that haven to regain her broken health and it was in hill-girt Dansville that Clara Barton founded the first chapter of the American Red Cross and raised the banner of mercy that flies wherever humanity is in distress.

". . . unto to the hills whence cometh my help."

The steep hills shelter and keep warm the valley earth where green and growing things flourish and mature weeks ahead of those in neighboring and less protected soil. Dansville owes her prestige as a nursery center to the shielding hills.

Down the hills pour the cold swift waters of the Stony Brook, the Little Mill and the Mill Creeks and the Canaseraga, which is the chief tributary of the Genesee River. The streams rush through the deep gorges, and the sylvan glens, over the rocky ledges, one through the romantic beauty of Poag's Hole, unromantically named after a Tory squatter, another through the masterpiece of nature that is 500-acre Stony Brook State Park at Dansville's southern gate.

For all her scenic glory and her distinguished history, Dansville is a mighty practical, business-like place. This village of more than 5,000, largest in Livingston County, serving a trading area of nearly 10,000, is an industrial community although no pall of smoke hangs over her. Dansville is a live, progressive village—as well as a distinctive, tidy and comely one.

* * * *

On a trail leading from the Genesee to the Canisteo and thence over the mountains into Pennsylvania, the Senecas built a small village, probably in the late years of the 17th Century, on the site of Dansville. They called it Ganosgaro, which meant "among the milkweeds."

Over the trail, in the early time came a mongrel outlaw band from Canisteo Castle. The Seneca warriors of Ganosgaro battled them on the eastern heights and, in the fighting, a noted Seneca chief was slain. His body was brought to the Indian burying ground at Ganosgaro and when the German Lutheran Church was built, it rested directly under the altar. Main Street cuts through the old graveyard site and now the Lutheran Church is vanished from the scene.

When the white settlers came, they found about 15 unoccupied huts in the Indian village. The Redskins lingered around old camping grounds on the outskirts of the settlement for some years, and their Demosthenes, Red Jacket, paid occasional visits to the town and under the influence of firewater made the street ring with his oratorical thunder.

When the white settlers came, they found about 15 unoccupied huts in the Indian village. The Redskins lingered around old camping grounds on the outskirts of the settlement for some years, and their Demosthenes, Red Jacket, paid occasional visits to the town and under the influence of firewater made the street ring with his oratorical thunder.

Unlike the more northern Stage Coach Towns, Dansville's pioneers came from the southward. from Pennsylvania and New Jersey, and not from the East and New England. They came over the road that Charles Williamson, the Pulteney land agent, had cut over the mountains through the forest, all the way from Williamsport to his long-gone "city of Williamsburg" at the confluence of the Canaseraga and the Genesee.

Settlement began on the site of Dansville in 1795 and it seems established that Cornelius McCoy was the first on the scene, although there have been conflicting claims. At any rate there was by 1796 a little settlement in the valley.

An early arrival was enterprising Daniel Faulkner, "Cap'n Dan," from Danville, Pa. He induced 15 families to settle in the new community, he opened the first store and the first saw mill and he laid out the town. It was natural that Dansville should be named after "Cap'n Dan."

Like many another town in the Genesee Country, Dansville felt the imprint of the bold planning of Land Agent Williamson. He built grist and saw mills and highways to them. In 1800 he sold 700 acres to a mill-site-conscious veteran of the Revolution named Nathaniel Rochester, who had come into the Genesee Country on horseback with his fellow Marylanders, Charles Carroll and William Fit711ugh.

In 1810 Colonel Rochester pulled up stakes in Maryland and came over the mountains with his family and his slaves to live in Dansville. There he established the first paper mill in Western New York. Old records show that in 1811 he freed two slaves, "Benjamin, aged about 16 and Cassandra, about 14."

The colonel, with Carroll and Fitzhugh, had bought 100 acres of swamp at the Falls of the Genesee, 46 miles to the northward, and in 1811 he told a friend that "Dansville will be a fine village but the Falls is capable of great things . . . and I am too old to build two towns." He was 60 and he chose to build the town that bears his name today. In 1815 he left Dansville to live in East Bloomfield before moving to Rochesterville.

A lasting reminder of Nathaniel Rochester's short residence in Dansville is the Church Square he gave the village, on which stand four houses of worship today.

* * * *

Lumbering was an important pioneer industry. Saw mills and paper mills hummed along the Canaseraga and lumber was floated down the stream in arks, raft-like boats made of planks. Dansville was "the fastest growing town in Livingston County" even in her infancy.

Her pioneers were a mixture of English, Scotch, Irish, Dutch and German bloods. Here was no heavy Yankee strain as in other places in the Genesee Country. After the Patriot War of 1839 some Canadian refugees settled at Dansville. It was about that time that the thrifty German emigrants came to the Sandy Hill region.

Building of a spur of the Genesee Valley Canal from Mt. Morris in 1841 spelled the start of a 10-year boom for Dansville. It became a busy canal port, an important shipping point. Lumber poured in from as far south as Coudersport, Pa., in streams of sleighs in winter. Canal boats were built in the yards of Dansville. Packets ran from New York to the village, the southern terminus of the canal, insofar as passenger traffic was concerned. A boat left Rochester every evening at 7 and arrived at Dansville at 9 in the morning. The fare was $1.50 with board, $1.25 without. Picturesque canal captains lived in Dansville. It was a roaring purple decade along the towpath.

At first the canal ended a half mile north of the business section. In 1844 a $6,000 fund was raised and a slip was dug to reach the heart of the village. When state officials heard of this, they sent a scow laden with rough and tumble fighters to prevent the men of Dansville from cutting through the canal bank and letting water into the slip. The village stalwarts mobilized with clubs, fists and stones and put the scow gang to flight. It was a fierce battle they won in the mud. Thirty leading citizens were indicted—but never brought to trial—for illegal tapping of the state waters. For years the scene of the conflict was called Battle Street—until residents had it renamed Booth.

In those days the center of things was along the canal. On Canal Street (now Jefferson) were five big hotels, including the four-story brick Eagle which still stands, no longer a hotel, at the West Avenue corner. Protruding from an old building along the tracks of the Dansvilie & Mount Morris Railroad is a reminder of the old canal—an iron hook to which once the boats were tied. North of the village are still traces of the masonry of the old ditch, which was abandoned in 1878.

A quarter of a century before that, the whistle of the Iron Horse had sounded the knell of the canal boom. When in 1852 the Buffalo, Corning, & New York Railroad (now the Erie) reached Wayland, that village became the shipping point of the region and the canal traffic dwindled. Stage lines out of Dansville to the railroads did a rushing business.

Dansville felt keenly her lack of rail facilities and led in the movement to build the 15 mile Dansville-Mount Morris line, corrnpleted in 1872. The road, despite its brevity, is an important one. When the Lackawanna Railroad came in 1882-83, it put its tracks on the hillside and its station on a lofty summit a mile from the village. The view from that station is stupendous. So too is the haul up the steep ascent.

So it is the D and M that hauls the freight in and out of Dansville. The shipments are carried eight miles down the valley and transferred to the Lackawanna tracks via "the Groveland crossover."

* * * *

In 1796 the settlers heard a noise like thunder, followed by the rush of waters. A new stream had burst out of the eastern hillside 200 feet above the valley level. The water was pure and cold and they called it "The All Healing Spring."

The health resort began there in 1853 when Nathaniel Bingham and Lyman Granger built the first "water cure," Five years later a bearded physician named James Caleb Jackson took over. The resort remained in the control of the Jackson family for over half a century. A dozen cottages were erected around the main building and health seekers began flocking to "Our Home on the Hillside," as it first was known. In turn it bore the names of Our Home Hygenic Institute, the Jackson Sanatorium and the best known one, the Jackson Health Resort. For many years the dominating figures of the institution were Dr. James H. Jackson, son of the founder, and his wife, Dr. Kate.

In 1878 the soon-to-be-famous Dr. John Harvey Kellogg came from Battle Creek to study the Jackson health methods which centered on rest, fresh air, exercise and simple diet. Simplicity in dress also was stressed and on the Jackson staff was Dr. Harriet Austin who caused a stir by advocating and wearing an "American costume" for women—trousers and a Prince Albertish coat.

The main building was destroyed by fire in 1882 and the next year the present imposing red structure of brick and steel, so conspicuous on its green hillside, arose. The health resort was at the height of its fame. The Jackson magazine, "Laws of Life," had a national circulation of 10,000 before it folded in 1893. The Jacksons made and marketed the first cooked, ready-to-eat cereal, granula. The sanatorium, with its staff and famous guests, had a cultural influence on the village.

But the era of "the water cure" was fading. In 1914 the resort went into receivership. During World War I the government used it for the care of veterans suffering from nervous disorders. After the government relinquished it in 1921, it passed into the hands of a syndicate of physicians.

In 1929 the health center was sold to the fabulous Bernarr Macfadden, the New York publisher and exponent of physical culture. Renamed the Physical Culture Hotel, it has taken on a new lease of life. The Macfadden system in many ways follows the simple old Jackson health formula. The PCH, as the village knows it, is a busy place summers. The 78-year-old Macfadden pays an occasional visit, sometimes in his own airplane.

In the 1930's the national spotlight swung on the hillside hotel. It was the terminus of the "Cracked Wheat" or "Bunion Derby" of devotees of the Macfadden diet who hoofed it to Dansville from New York and Cleveland.

* * * *

Of all the famous visitors who came to the health resort—and they have been many—the advent of Clara Barton in 1876 was the most significant.

A shy spinster, a government clerk in Washington, she had gone out on the battlefields of the Civil War to nurse, feed and comfort the Union soldiers. After the war she visited Geneva, seat of the International Red Cross organization, founded in 1864. She began a long tight for adherence of the United States to the Treaty of Geneva by which 21 nations had already set up an International Red Cross. She went on strenuous lecture tours for her cause and her health broke down. Ordered to take a complete rest, she came to the Jackson "water cure."

Clara Barton had been in Dansville before. In 1866 while on a speaking tour, she had taken a stage from Wayland to Dansville. A mile out of the latter village, a wheel had come off the vehicle and she had walked into town through the snow.

Miss Barton regained her health in the hillside retreat. She became so fond of Dansville that she bought a house, a solid, two-story house that still stands under old trees on Health Street.

Renewing her campaign to get the United States to ratify the Treaty of Geneva, she organized in Washington in May, 1881, the American Association of the Red Cross. Her Dansville neighbors, desiring to aid in this work, asked her to help them organize. So it was that, on August 22, 1881, in St. Paul's Lutheran Church, the first local society of the Red Cross in America (later renamed Clara Barton Chapter No. 1) came into being. There were 57 charter members. In October a second unit was formed to Rochester, with the able help of another indomitable spinster, Susan Brownell Anthony.

The Dansville society found work to do right at the start. There had been a terrible forest fire in Michigan and Miss Barton's home became a headquarters for the collection of supplies and funds. In the Dansville Library is a time-worn flag with the familiar cross of red on a field of white. It flew from the masthead of the first Red Cross relief boat to ply American waters, the Joshua V. Throop, which in 1884, with Clara Barton aboard, went to the scene of the Ohio and Mississippi flood disaster.

In 1886 Miss Barton, with tears in her eyes, at a public meeting bade farewell to Dansville, "the pretty town that has given me back my strength." The rest of her career is familiar history.

On Sept. 9, 1931, the natural amphitheater of Stony Brook Park was jammed with thousands gathered for the 50th anniversary of the founding of the first Red Cross chapter in America. President Herbert Hoover by radio and Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt in a personal appearance, led the chorus of tributes to Clara Barton and her Dansville neighbors who had made history.

Products made in Dansville, and they are a diversified lot, are shipped all over the world. Fruit trees, shade trees and ornamental shrubs, grown in the many nurseries that dot the sheltered valley and the hillsides, have made Dansville an important nursery center since 1851. There also is a sizeable vineyard industry but not on the scale of other days. One of the pioneer nurseries recently has pioneered in a system of erosion control by means of a series of ditches that stem the rush of water down the slopes and prevent washaways.

King-pin of the industries is the big Foster-Wheeler plant, where steam generating equipment for power plants and marine service is made for a world trade.

Dansville has been making paper since Nathaniel Rochester's day. When straw, instead of wood pulp, was used, this was the first place in the United States where the straw was bleached to make the paper whiter. The Berwin Paper Company, Inc., maker of waxed and napkin paper, carries on the tradition. The Blum Shoe Mfg. Company, producing felt, fabric, and leather house slippers, started in 1885 with three or four hands. It grew out of the custom shoemaking shop of John Blum, and now is operated by the third generation of the Blum family.

School teachers all over the land know Dansville as the home of the F. A. Owen Company, publishers of The Instructor magazine for elementary teachers, and other teaching aids. The business was founded by the late F. A. Owen in 1889 in the attic of a grocery store at South Dansville as the Empire State Teachers Class, believed to have been the first correspondence school in America. In 1891 the Normal Instructor, as it was first known, was started and the next year the business was moved to Dansville—in a single room. It has a large modern plant in the heart of the village today.

One might add to the list of Dansville industries the Macfadden Hotel and Stony Brook State Park, which draws the tourists.

* * * *

A showplace of Dansville is its library, housed in the stately pillared homestead that Joshua Shepard, whose son Charles married into the Nathaniel Rochester clan, built in 1823-24. In 1924 the Shepard family presented it to the village as a memorial to their ancestors.

Joshua Shepard's grandson, one of Dansville's most distinguished sons, Gen. Charles McC. Reeve, was born in that homestead and was a generous patron of the library. Gen. Reeve, a Spanish-American War veteran, who shared in the capture of Manila and was the first military chief of police of the Philippine city, as well as a leading citizen of Minneapolis, died last June in his 100th year.

Few villages have so complete, large and modern an airport as the one the edge of Dansville, government built in 1927 and owned by the Town of North Dansville.

A landmark in the three-story former Dansville Seminary on the eastern hillside, built in 1860 and since 1910 serving as a State Home for Aged Couples and King's Daughters. The village is proud of its 47-bed General Hospital.

Dansville has a vigorous community spirit as evidenced recently when the Deer Park, a favorite picnic ground in horse and buggy days, faced despoilation by lumber interests. The Fish and Game Club stepped in and through popular subscription bought the park and put up a club house. It is worth going miles to see the dogwood blooming at the Deer Park in the spring.

When I visited Dansville in early June, the peonies were in full bloom in the gardens along the shady streets. It was two weeks later that the bushes in my own yard flowered. But Rochester does not lie in the shelter of mighty hills.

* * * *

Dansville had a native son, who attained nationwide fame in an unorthodox way. His name was Alonzo J. Whiteman and he came of a fine old Dansville family. A graduate of two colleges, he went West as a young man. At 25 he was a member of the Minnesota State Senate. He became mayor of Duluth, chairman of the Democratic State Committee, president of a bank, owner of a newspaper, a commanding figure in the young Northwest of the 1880's.

Then Lon Whiteman gambled away a fortune at faro and poker and in the Chicago Wheat Pit. He became one of the slickest check raisers in the nation, member of a band of bold and crafty swindlers. Although the Pinkertons were always on his trail and he was arrested 43 times, he served less than five years behind the bars. He knew penury in his old age but he never lost his superb aplomb and in his native village he was well liked, this suave, personable man who put his great talents to evil use.

The week of Aug. 11-17, 1946, was a gala time in Dansville, a combination Old Home Week and huge birthday party, marking the centennial of the village's incorporation and the sesquicentennial of its settlement. It was observed with pageantry, parades and oratory and many former residents returned. The chairman of the planning committee for the fete was historically-minded Attorney Edward E. Brogan. He told me where to find the iron hook beside the old canal and expounded the theory that in ancient times the river Genesee ran through the valley in which Dansville nestles. But he couldn't tell me how Paradise Alley got its name. Most prized of Brogan's possessions is the chair in which FDR sat when he visited Dansville at the Red Cross anniversary in 1931. Brogan is an active Democrat in Republican Livingston County.

Charles T. Lemen, town historian and former mayor, descendant of pioneer settlers, was born in Dansville in 1869. He has a wealth of memories as well as pictures and historical data of his village. When he was 14, he was a messenger boy and came to know Clara Barton, a "queenly woman, always kindly." He talked of other days—of the Heckman Opera House, destroyed by fire in 1932, and the road shows and the home talent plays on its old stage; of the days when Stony Brook Glen was privately owned and the now defunct Shawmut Railroad ran Sunday excursions there from Hornell and Pennsylvania points; of the picnics in the shadow of the bridge 243 feet above the gorge over which Shawmut trains will never rumble again; of Warren Allen, one of the original Dansville "Flying Aliens," making a parachute drop, in a derby hat, from the top of the high trestle in pre-aviation days.

* * * *

Lift up your eyes to the hills of Dansville—to East Hill, Ossian Hill, Sandy Hill, and the rest. Catch the warm, unaffected spirit of this fine old town and your heart will be uplifted, too.

BACK in 1848 John Hess chewed on his goose quill and mulled over his problem.

He was supervisor of the Steuben County town of Cohocton out of which a new township was to be sliced and the State Legislature had given him the task of selecting a name for it.

He had submitted Millville but the solons rejected it because there already was a Millville in the state. They told John Hess to try again. Time was short. The session in Albany was drawing to its close and before the new town could be sanctioned, it had to have a name.

John Hess took his problem to his friend, Myron Patchin, the peace justice. As they pondered the matter, Patchin whistled a few bars of the hymn tune "Wayland." Suddenly his face lit up and he cried out: "John, I've got it. Wayland is the name!"

And that is how the township in the hills of northern Steuben at the borders of Livingston County, and its principal village, now the capital of a resurgent "potato kingdom," got their names.

* * * *

The site of Wayland village was settled as early as 1807 when Christopher Zimmerman of sturdy Pennsylvania Dutch stock, built a house where the Bryant Hotel stands and set out an apple orchard that lasted for 75 years.

During the first half of the century, the business centers of the town were Patchin Mills, now Patchinville, on the road to Hornell, and Perkinsville, to the west, which began with Benjamin Perkins' saw mill in 1812. They are hamlets today.

Wayland is a daughter of the Iron Horse. For there were few buildings on its site until 1852. That was the year a branch of the Erie Railroad nosed its way up through the hills from Corning. The village's "coming out party" was a gala excursion from Bath in July, 1852. It remained the terminal of the road for some months before the branch was completed to Avon and eventually Rochester. Huge piles of wood, fuel for the locomotives of the period, were stacked at Wayland. Astute business men began buying land and laying out streets and a brisk town came into being around the tracks.

Most people preferred the new 30-mile-an-hour railroad to the old 3-mile-an-hour packet boats of the Genesee Valley Canal. That was a bitter pill for Wayland's proud neighbor. Dansville, on the canal but off the railroad. Wayland became the shipping point for the region. A plank road was built to Dansville and paid for out of tolls.

Dansville people had to take the stage to the railroad at upstart Wayland and it is recorded that they, arrayed in their Sunday best, always took pains to announce in the railroad coaches that they did not live in Wayland although they got aboard there. In a few years Dansville had a railroad and could lift its head again.

In its heyday more than a dozen passenger trains passed each way daily over the Erie branch. Now all passenger service has been abandoned.

In 1882 the Lackawanna thrust its way through the hills and reached Wayland. But the nearest station was Perkinsville and the railroad was deaf to pleas for a depot in Wayland.

A village business man, H. G. Pierce, went into action. He knew that on a certain hour, "The Comet," the special car of the railroad officials, would be passing through. There happened to be a lot of farmers in town with their teams and wagons that day. Pierce had them concentrated at the Lackawanna crossing when the special whizzed past. "The Comet" ground to an unscheduled halt and a railroad bigwig stepped down to ask the meaning of the heavy traffic in the street. He was told that the farmers "were hauling potatoes to the Erie." In a short time Wayland had a station on the D., L. & W.

In 1888 Wayland became a terminus of the Pittsburgh, Shawmut & Northern. The Shawmut, an important "feeder" line in its day, only recently gave up the ghost.

In 1888 Wayland became a terminus of the Pittsburgh, Shawmut & Northern. The Shawmut, an important "feeder" line in its day, only recently gave up the ghost.

It was inevitable that Wayland, on three railroads and in the heart of a productive farming area, grew rapidly. Thrifty German emigrants who came in the 1850's played no small role in its development and their descendants form a considerable part of its population today. It was mostly the men of Erin who built the Erie and many Irish families settled in the community to mix with the Yankees and Pennsylvania Dutch who were the first corners.

Today this brisk village has a population of more than 1,800. It is a solid, comfortable sort of a place. On its shady streets there are no palaces. Nor are there any hovels. Its setting is picturesque, ringed by hills that rise to a height of 1,372 feet above sea level.

Publisher G. T. Toole, under the masthead of his weekly Register, states the village's case succinctly and well: "Wayland—a natural trading center for a thriving industrial and farming area."

* * * *

Wayland has always had its industries although they changed with the years. Out on the southwestern edge of the village was one of the first Portland cement plants in the nation. In 1892 Thomas Millen & Son began mining the marl from the swamps there and making it into cement. The industry faded out with the use of crushed limestone for cement making. Once a half dozen kilns towered like huge brown silos above the flats. Now only one remains to tell of a once important industry. And the old marl beds are ponds, stocked with fish.

Around the turn of the century Wayland was the home of an incubator factory. The leading industry for years has been the Gunlocke Chair Company, which makes school and office furniture and which was founded in 1902. It employs more than 300 hands. There also are the big Wayland Canning Company's plant, once locally owned now a part of the General Foods chain, and the Huguet silk mill.

The first settlers found the soil good for raising potatoes and "spuds" have always been a major crop of the region. About seven years ago potato production got a mighty "shot in the arm when Maine and Long Island growers moved in. They are big operators and with modern machinery, lavish use of fertilizer and planting of large acreages, usually on the stoniest hills, instead of small patches, they have revolutionized potato farming in the region. The fall harvest is a colossal affair, when hundreds of hands, many of them migrants, invade the fields and the long convoys of trucks roll off with their loads.

There are "potato kings" like Maine's Jack Bishop, who operates some 4,000 acres and Long Island's Hoefner, who keeps a small army of Negro workers on his payroll the year around. Winters they work in his Florida orange groves; summer finds therm on his Long Island potato farms and autumn brings them to the Wayland fields.

South of Wayland, on the road to Hornell is Loon Lake, a sparkling little gem. Its shores are lined with summer cottages, mostly those of Hornellians. It has an immense dance hall. The view I saw from a summit on the North Cohocton road above the radiant waters, was like a splendid mosaic. The folds of hills stretching as far as the eye could see, were bathed in sunlight. Mingled with the gold of the grain and the rich green of the woods and the fields were splashes of white, the blossoms of acre upon acre of potato vines. They were the banners of the "Potato Kingdom."

* * * *

"Old Tilden" belongs to Wayland folklore. A century ago he lived alone in a hut on the fringe of the settlement, near the woods. He earned his living by making lamp black and his sooty visage accentuated his eccentric ways. He was not a temperate man and when in his cups would light a great brush fire in the woods and as the flames leaped high above the trees, would dance around the flames, emitting blood-chilling yells. "Old Tilden" became a sort of bogeyman to the young children and timid spinsters of the neighborhood.

One day a quiet-spoken, aloof-mannered young man in city clothes, crowned with a silk hat, came to town. He said he was "Old Tilden's" nephew and he took the old man away with him. Wayland never saw its bogeyman again. in. But it heard about his nephew. He became one of New York's most famous governors and almost went to the White House. Many folks think he was cheated out of the Presidency. His name was Samuel J. Tilden.

There were some much earlier residents whose story is hidden in the mists of the past. Edward A. Gilroy, local attorney, whose hobby is ancient Indian history, has found definite traces of Algonquin occupation in the town. He cited the find in a marl bed of a rare "ceremonial stone," a piece of slate with a bird carved on it. He scoured the countryside for relics of Indian culture and then came on his finest trophies right on the farm where he was born—arrowheads, tomahawk heads and other objects produced by aboriginal workers in stone.

More than 30 years ago another old resident was dug up by excavators over Perkinsville way. They unearthed the bones of one of the largest mastodons ever found in the stare. The remains are now on view in the State Museum in Albany.

Wayland's "Grand Old Man" is William Wayland Clark, retired justice of the Supreme Court, president of the First National Bank for nearly 50 years and all outstanding citizen, now in his 90th year.

A local boy who made good in the big city (it happened to be Buffalo) is Supreme Court justice George A. Rowe, a past imperial potentate of the Ancient Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine.

And Wayland for the last three years has been the home of a successful and prolific writer of Western stories, Paul Evan Lehman.

A native of nearby Patchinville was the late Frank C. Patchin, author of many popular adventure stories for the young and a newspaper man in New York and Rochester.

August 30, 1943, is a day Wayland will always remember. The rays of the late afternoon sun were dappling the hills when the Lackawanna Flyer, pride of "The Road of Anthracite," roaring westward at high speed, one mile west of Wayland station, struck a switch engine, inexplicably on the main track. There was a deafening crash, then the screams of the dying, the injured, the panic-stricken. Trapped in the wrecked coaches, many were scalded to death by live steam from the locomotive boiler.

The 15-bed Wayland Hospital, the Masonic Temple and private homes were thrown open to the victims. It was wartime and there was a blackout that night. But one spot in Western New York was exempt—that scene of horror and confusion along the Lackawanna tracks. The toll of the wreck eventually reached 29 dead and 150 injured. It was one of the worst disasters in Upstate New York's history.

* * * *

Little remains of the olden glory of Patchin Mills. A huddle of buildings, a sign at the crossroads, a feed mill, that's Patchinville today. But the fourth generation of the family still lives on the acres where the first Patchin, Walter, settled in 1814.

It was he who built the big Patchin Mills Hotel, long and low and painted a fiery red, on the hill at the crossroads. It had 20 rooms and 20 fireplaces and it was a stop on the stage coach lire from Dansville to Elmira. In his "History of Wayland," Charles M. Jervis penned this graphic picture of stage coach. days:

"The post horses were changed, the mails shifted, the bugle sounded, the whip cracked over the leaders' heads and off the coach lumbered, the leathern springs creaking under its load of passengers in wide-brimmed beaver hats and poke bonnets and the 'boot' filled with leather-covered trunks studded with brass nails. . . . It was the sight of the time."

The inn is gone, along with the store, the cheese factory and the postoffice. Gone, too, are the two race tracks that were part of Patchinhurst, the breeding stables operated for 25 years before World War I by Bert C. Patchin, the present occupant of the ancestral acres. One was a half-mile track. The other, a quarter mile in length, was entirely covered so that the horses might be exercised in winter. Bert Patchin bred trotters and show horses and took his colts to the big shows in New York's Madison Square Garden.

Another branch of the clan numbered among its members Gordon Patchin, a onetime Assemblyman.

For two decades many feet—some of them famous ones—have beaten a patch to Patchinville, to the studio of Bert Patchin's wife, Sally of the gay heart and the merry laugh. The hand-painted baskets and pottery of Philadelphia-born and Paris-educated Sally Patchin have won more than local favor. To her studio have come such notables as Lily Pons, George Eastman, Roger Babson and Bernarr Macfadden.

And now to the valley of the Conhocton, where in the long ago Land Agent Charles Williamson's road-building choppers blazed a tree at every mile.

At "the 22-mile tree," denoting its distance from Bath, Joseph Biven built a tavern in 1794. First known as Biven's Corners, it was renamed North Cohocton in 1825. When they named their towns, the pioneers somehow dropped the "n" from the name of the river which in the Indian language meant "log in the water."

When the railroad skipped North Cohocton, it was overshadowed by its southern neighbor, now called Atlanta, but long known as "Blood's Station," after Calvin Blood, a pioneer. In that neighborhood in the mid '80's a tenant farmer's son at the age of 10 became the local delivery agent for The Rochester Democrat and Chronicle. That boy was Frank Gannett and he owns The Democrat and Chronicle and 20 other newspapers today.

Where the axmen blazed the "18-mile tree," a settlement first called Liberty, because of the tall liberty pole erected there, began in 1805. Eighty years later it was rechristened Cohocton.

An early settler was one Joseph Chamberlain, who, it is related, arrived with a dog and a cow and all his other possessions, save his ax, in a small pack. When he became hungry, he cut a notch in a log and driving the cow astride it, milked into the notch. Then he crumbled his bread in the "bowl" and ate his bread and milk with a wooden spoon. For him, "wilderness was paradise enow."

Cohocton on the Conhocton River, on the Erie and Lackawanna Railroads and on the old stage route to Bath is a folksy, unassuming village of the 1,000 population class. Like Wayland, her ethnic stream received a heavy infusion of German blood nearly 90 years ago. And she shares in the potato boom brought on by the advent of the Maine and Long Island growers.

In Cohocton is the largest buckwheat flour mill in the world, that of the Larrowe Corporation which began as a custom mill and switched to the buckwheat business in the 1890's. Much of the buckwheat is grown in the region although there is considerable "milling in transit" of shipments from Canada and other points.

A boy born on a Cohocton farm achieved fame and fortune in a rather unusual field. He was Orson Squire Fowler, in his time the high priest of phrenology, the "science" of reading human character in the contour of human heads.

Fowler was a classmate of Henry Ward Beecher at Amherst and they read skulls together in the early days of the fad which bloomed from 1830 to the Civil War. Beecher decided on a theological career but Fowler saw gold in head reading. He went to New York, opened an office and sent to Cohocton for his brother, Lorenzo, and his sister, Charlotte. They also became adept in the art. Orson wrote books and lectured all over the nation. He read the craniums of famous and wealthy people—and never attributed an unworthy trait to any of them. When he gave a demonstration in his native hills, he asked to be blindfolded because he "knew his subjects too well."

In his late years, Fowler built a strange, five-story, eight-sided house on the Hudson near Fishkill. It was called "Fowler's Folly." The phrenologist had to abandon it because seepage in its basement brought on typhoid fever.

Another native son who was a "scientist" in another field was Dwight Larrowe. Under the name of Professor Loisette, he lectured widely after the Civil War on his memory training system, a sort of "Addison Sims of Seattle" method. The professor sleeps in the family cemetery at Cohocton.

Manley McDowell has practiced law in the village for 49 years. His father was a Cohocton lawyer. His son, Robert. present town supervisor, carries on the family tradition. The veteran attorney from his office window pointed out across the street a weather beaten, three-story building that was an inn in stage coach days. He told how fire had leveled three hotels on one village corner; of the cigar factory that employed 100 men in the 1880's and how the west side of town came to be nicknamed "Tripp Knock."

It seems that in a celebrated barroom fight there years ago, the three Tripp brothers took on all corners and knocked them all out.

To Next chapter

![]() To GenWeb of Monroe Co. page.

To GenWeb of Monroe Co. page.