Cradle of the Stars

Cradle of the StarsBORN—In the year 1825, of New England parentage and suckled by the Clinton Ditch, on the farm of Daniel Spencer in the town of Ogden, the port called Spencer's Basin.

But when people got to calling the place simply "The Basin," the village fathers renamed it Spencerport. There were already too many "basins" on the canal. Besides the new name was more seemly for a port of growing importance—and it was more dignified.

Seemliness and dignity belong to New England and the New England strain is strong in the Ogden blood. It was put there 143 years ago when Ogden Town was Fairfield, long before there was a canal or any ports or basins; when the first settlers from New England put to the plow the land in which still live so many of their descendants, Spencers among them.

The pretty village at Rochester's western gate has certain New Englandish physical characteristics, too. The visitor notes the snug, unpretentious, homelike homes, so many of them painted white, under giant elms; the thin white spire—that of a Congregational Church, again in the New England tradition—reaching skyward above the town; the preponderance of Anglo-Saxon residents; the absence either of excessive wealth or extreme poverty; the tranquility of the main street with its chairs where old men may sit in the sun. The hasty, observer is likely to add tip all these things and get "New England."

But Spencerport is not New England. She is Western New York. Above all she is herself,

Because only 10 miles separate the residential village and the industrial city and because so many people work in Rochester and sleep in Spencerport, some might say "Oh, another suburb."

Again, they are wrong. Spencerport is not "another suburb." She is Spencerport, serene, decorous, ever charming and with a proper New Englandish dignity.

* * * *

The town hall at East Haddam, Conn. was crowded for the "Genesee meeting." James Wadsworth spoke with fire and feeling of the possibilities for settlers in the Genesee Country. True, he had land to sell—at $2 an acre, but more than that, he had a vision of a fertile and prosperous countryside where all was wilderness. The year was 1802.

The town hall at East Haddam, Conn. was crowded for the "Genesee meeting." James Wadsworth spoke with fire and feeling of the possibilities for settlers in the Genesee Country. True, he had land to sell—at $2 an acre, but more than that, he had a vision of a fertile and prosperous countryside where all was wilderness. The year was 1802.

In the audience was young George Willey. Soon he was on his way to the Genesee Country afoot, his ax slung over his shoulder. He was the first settler to rear a cabin in the town that was to bear the name of William Ogden of New York, an early land speculator. For that he received a prize offered by Wadsworth.

Let a native-born poetess, Mrs. Augusta E. Nichols-Rich, reading the centennial ode at Ogden's 100th anniversary celebration in 1902, go on with the tale of the award:

For a conservative sort of town, Ogden had a lusty beginning.

Other pioneers came from New England, the four tall Colby brothers, the Websters, the three Spencers, William H., Daniel and Austin; the Nicholses, the Hills, the Trues and many more whose descendants still live in the neighborhood.

Ogden Center became the principal settlement and James Wadsworth had great hopes for it. Only recently has the last Wadsworth land in Ogden passed out of the hands of the Valley dynasty. West of the Center another hamlet was founded with the curious name of Ogden Town Pump because of the pump that stood for many years at the intersection of the highways.

The star of Ogden Center waned as the Ditch pushed through Spencer's farm and lots were sold for the village, that soon became a shipping point for lumber, grain, and fruit and was known far and wide as "The Basin."

A cultural child of the old Center still survives in the Ogden Farmers' Library now housed in the Spencerport Village Building. It was founded in a store in 1815 and only three free libraries in the state are older—and one of them is the Farmers Library of Garbutt, born in 1805.

By 1876 the Ogden Library was dormant and so it remained until 1908, when, under the leadership of the late Supreme Court Justice George A. Benton, one of Spencerport's most distinguished and influential men, it was reorganized and moved to the canal village. The old books, 141 of them, were collected from scattered homes and one can see them today in the village library. One book plate bears the date of 1799.

James Wadsworth deeded to the association two acres of land with the stipulation that it could never be sold. So today the library has on its hands some real estate for which it has scant use.

* * * *

In the Farmers' Library is a framed picture of an old gentleman with luxuriant whiskers. It might be Longfellow or Whittier. It is one of their literary contemporaries, John Townsend Trowbridge. He was born in a log house in Nichols Street in 1827. His name is hardly remembered now but he wrote 50 volumes that were best sellers in their time.

Trowbridge's "Neighbor Jackwood," his most popular work, written in 1857, was one of the first realistic novels of New England life. He also wrote "Cudjo's Cave," depicting the thrilling adventures of a runaway slave; the Jack Hazard series, the Title Mill series, all prized by young readers who devoured their by candlelight.

Trowbridge was a poet, too. His first verse was published in a Rochester newspaper when he was 17. His most famous verse, "Darius Green and His Flying Machine," is said to have been based upon the experiments in aviation of an unidentified Ogden neighbor.

The author, when 27 years old, went to New York and later to Arlington, Mass., where he died at the age of 88. At the time of the Ogden Centennial in 1902, be paid this tribute to the old library in a letter:

"For me it held infinite riches, for there were the great Waverly novels, the Leather Stocking tales of Cooper, Shakespeare, Byron, Plutarch, Hume and the Spectator—history, poetry, romance."

Today an historical marker stands before the house in Nichols Street where a distinguished American man of letters lived as a boy.

Some years ago, on motion of the scholarly Ernest R. Clark, then a resident of Spencerport, the village school was renamed the John T. Trowbridge School. But somehow the name never stuck. But then, Ernest R. Clark has led many other lost causes.

Now after many years another Spencerport youth is following the Trowbridge tradition. William Kehoe is only 22; he was graduated from the village high school in 1940 and won the Avery Hopwood prize for literature while a student at the University of Michigan. His first novel, "Sweep of Dust" is out and his mother, Mrs. Mable Kehoe, who lives in Spencerport, and all the neighbors are proud of Bill and you see "Sweep of Dust" on many a village table.

* * * *

The Congregational Church is really a bit of New England—pearly white with an old fashioned stone basement with side door and a generous sweep of lawn, its spire dominating the village scene.

In 1850 it broke off, amid some acrimony, from the Ogden Presbyterian Church. The founders of the new parish vowed to have a spire higher than the mother church. The new edifice, dedicated in February, 1852, fulfilled the pledge. The building burned down in November of the same year but the doughty flock soon rebuilt it, with a spire higher than the first one.

The first minister was the Rev. James Morton Dill. During his pastorate, in 1854, a son, who was christened James Brooks Dill, arrived at the parsonage. This boy went to New York and was one of the most successful corporation lawyers of America.

The boy who was born in a Spencerport parsonage performed superservice for the big corporations. He is said to have been the first lawyer ever to receive a million dollar fee. That was for weaving together the intricate fabric of the Steel Trust. Mark Sullivan, in "Our Times," suggests that Dill was the father of the law that has made New Jersey such a slug haven for giant corporations.

Dill died in 1910 but not before he had given a memorial window to the church where his father preached and had made a trip back to his birthplace to deliver an address. No one recalls what he said on that occasion but Sullivan in his book states that Dill once began a Harvard lecture with the proud declaration that "I am the lawyer for a billion dollars of invested capital."

* * * *

So much for the minister's son. Now for a minister's daughter who once called Spencerport home. Around 1910 the Methodist Conference assigned the Rev. Peter Thompson to the Spencerport church. The Rev. Peter, a smallish man, with a good singing voice, had a second wife, two daughters and a son. The younger daughter, Margaret, and the son Peter Jr., attended the local school. The older daughter attended high school at Hamburg, their former home, and later, Syracuse University. She was in Spencerport only at vacation time during her father's five-year pastorate. Her name was Dorothy. Yes, she was THE Dorothy Thompson.

Mrs. Florence Ring, who as a girl lived across the street from the Thompsons and who sang with Dorothy in the church choir, remembers the teen age Thompson daughter as "full of pep, smart and witty. She was slender, not very tall, with brown hair and blue eyes." She sang alto in the choir.

And once when the Rev. Peter was ill, Dorothy Thompson, home from college, preached in his stead. The congregation of the Spencerport Methodist Church thus was one of the first audiences of the many that this famous woman has addressed.

* * * *

In the early days of the century, a tow headed girl lived in a humble home in Spencerport. Her name was Clara Luce. Later on Clara became Clair. She went to the village school and in vacations picked fruit in nearby orchards. She had a blond beauty; she was shapely; she loved to dance and above all, she had a flaming ambition.

So she came to Rochester to work in Eastman Kodak dark rooms to earn money for dancing lessons. She worked as a cigaret girl in a downtown restaurant. A Rochester dancing teacher, Florence Colebrook Powers, took the girl under her wing and after that Clair Luce's rise was rapid—but always marked by hard work and study of her art.

Her dancing feet carried her to Broadway and the Follies in 1927. She had a fling at the movies and the spoken stage; she married a millionaire and divorced him; she went to Europe, took London by storm and danced with Fred Astaire before King Edward VIII. She stayed in London during the blitz, giving shows for soldiers. Her name is known on two continents.

And that's the glamorous career of the tow headed girl who once lived "on the wrong side of the tracks" in Spencerport. N. Y.

* * * *

A few months ago a Spencerport High School alumnus, Eugene C. Auchter, whose mother lives in Elm Grove Road, was mentioned as the next Secretary of Agriculture. He did not get that job but Auchter, regarded as a foremost agricultural scientist, has recently taken over the directorship of Pine Apple Research in Hawaii. Edward Amish, now of Rochester, recalls how he and Gene Auchter used to skate from Spencerport to Elm Grove and back on the frozen Erie Canal.

* * * *

So Spencerport has been, in a sense, "the cradle of the stars." Few villages her size can boast so many boys and girls "who made good" in such varied fields as literature, journalism, finance, agriculture and the stage.

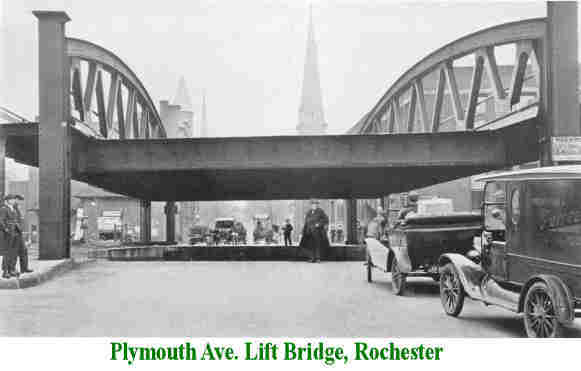

Approaching the village by canal boat, one is impressed by the seeming antiquity of the town. On either side of the lift bridge are two weather beaten frame buildings that look as old as the Ditch itself.

One of them is. The building with the cupola on the south corner has been a store since 1826.

The other, now the home of the Weekly Star, once was a grain warehouse and its shape fits the contours of the canal. It was built in 1876 after the fire that swept the whole side of the street.

Before the lift bridge, there was the "High Bridge." Then the farm wagons had to climb steep inclines and the "waterfront" scene was a busier one. The dock back of the Star building was laden with barrels of apples and potatoes and other produce.

The pioneer "Produce King" was James Upton. Soon after the Canal was built, two young men and their brides came riding westward on the ditch from Albany. One was Upton. The other was his chum, Leland Stanford. The Uptons got off at Spencerport. The Stanfords went on West to eventual riches and power. But James Upton played no insignificant role in his smaller sphere.

He built the mansion on the West Ridge that is now the home of the Ridgemont Country Club, which, according to his grandson, Charles A. Pomeroy, contained the first bath room in Monroe County. Upton began extensive growing and shipping of fruit and other produce, with Spencer's Basin his major port. After James Upton's death, his widow and family went to Spencerport to live. There the seven Upton sons grew up and made their impress on the community. Witness the Upton Building, the Upton Block, the one-time Upton Hotel and Upton Fire Department. All the sons, save Charles Stanford, the originator of the famous Rochester lamp, carried on their father's produce business.

Beside the lift bridge where the 83-year-old flagman, Joe Plucknett, keeps the state grounds so neat and well shrubbed, were once the canal hotels: The Palmer, later Tom Tunney's, and on the west end, Johnny Leonard's. Leonard, when Ogden went dry, opened the "Red Onion" just over the line in the town of Greece. On Union Street, where the Matheos ice cream plant now stands, was the three-story, white Lincoln House, once the Upton, and a well known hostelry in its day. It was razed some 20 years ago.

In the early 1900's the Rochester, Lockport and Buffalo electric line and the Barge Canal were being built at the same time. Workers on those projects, plus the Boating fruit pickers and the canallers, brought some lively times to the ordinary staid village.

Spencerport never was much of an industrial town. In the early days she had a blast furnace and a tannery. Later on there was a cannery and for many years the Hoy potato digger was made in the village. Before the Barge Canal was built, a slip ran from the old waterway north of the buildings on Union Street.

And there was—and is—the fireworks industry. Judge Benton once operated a fireworks factory along the canal. Eight years ago Amerigo Antonelli, Rochester "Fireworks King" and the son of the royal pyrotechnician to the King of Italy, began making fireworks in the sheds that dot the canal hank at the eastern end of the village. When the war came, he obtained large government contracts for bombs and grenades.

The arrest of Antonelli and some of his aides on charges of making defective bombs, their trials and convictions, followed by the passing of the plant into other and more reputable hands—that is recent history. Spencerporters prefer not to calk about it.

* * * *

And here are some stray fragments from the village's past and present:

The cable that stood for years in the bed of the old canal, a memento of the failure in the 1880s of the Belgian cable steam towing experiment between Buffalo and Rochester—the Malay brothers, Corydon and the younger Leroy, editing the Star as did their father before them, watching the village scene through the years and in later days the dwindling canal traffic from the windows of their plant that was once a grain warehouse—the glory of Spencerport as the greatest of cabbage shipping centers, around 1890. The shipments were by rail—Ernest R. Clark's boyhood memories of the old mill pond—Sig Sautelle's and other circuses coming to town by canal boat and the smaller shows that held forth can board ship—the state scow that David B. Hill Democrats in 1893 loaded with canal workers and floaters to turn the tide in Adams Basin caucus—the eternal rivalry in sports between Spencerport and Hilton—the dead whale that went on tour via canal boat and stank to the heavens—the schoolboy Cadets organized by Judge Benton—the lush days of the interurbans when 315 tickets to Rochester were sold in a single day—all these and many more memories, grave and gay, cluster around the town that began as a "basin" and ended as a "port."

* * * *

In 1802 a pioneer physician, Dr. John Webster, of Massachusetts bought land where now the Trimmer Road crosses the canal. When a small pox epidemic raged along the waterway he set up a hospital along the banks of the Ditch. One of his patients was a traveling evangelist, the Rev. Isaac Fister. On his recovery, the minister settled the doctor's bill by preaching for months without pay in Adams Basin Methodist Church. Later he became the regular pastor.

The doctor's son, Alvin, worked the farm after his father's death. A rabid Abolitionist, he maintained a station of the Underground Railway there. His son, the late Judson H., ran the farm for some years and during the winter, boarded the canal horses and mules, sometimes as many as 75 head. The place became known as Webster's Basin.

For nearly a decade after 1892, Judson Webster was one of the operators of the Buffalo and Rochester Transit Company which ran steam freight packets on the Canal.

A grove near Webster's Basin was the scene of many boat excursions from Rochester, sedate Sunday school picnics as well as gayer Elks parties. The William B. Kirk was the best known excursion boat.

Three miles west of Spencerport is Adams Basin, born of the Clinton Ditch, now a quiet hamlet with only the ruins of old warehouses to tell of the days when it was a considerable port.

First it bore the cumbersome name of Adams' and King's Basin, from two sets of brothers who founded it: Marcus, Abner and Myron Adams and Moses and Bradford King. They established stores, warehouses, sew mills. In its day Adams Basin shipped a lot of produce.

Marcus Adams in his memoirs recalls that the port was famous along the Ditch because of its shrewd horse traders who unloaded broken-down animals on the boatmen.

Abner Adams had the contract for digging the Ditch in the Adams Basin sector. He was the great-grandfather of Samuel Hopkins Adams, of Auburn, distinguished author of "Revelry," "Incredible Era" and of "Canal Town." The last named book is dedicated to his ancestor.

In the 1880's the saw mill of Joel Milliner was a busy place. Logs from the Canadian forests were rafted clown from Tonawanda with sometimes a single horse pulling six sections of logs hitched together. The logs were rolled off the Towpath into the nearby mill pond to be sawed by the Milliner mill.

United States Marshal Frank C. Blackford, now a Spencerport resident, was born at Adams Basin and his father, Joseph Blackford, conducted a store and large warehouse there. The marshal's blue eyes glisten as he talks about old canal days, of the old hotel and the cobbler, Pat McNarama, who told a wide eyed young Frank to get his shovel ready for "a boatload of pennies is coming on the canal." The marshal recalled swimming in the Ditch and sometimes encountering dead horses floating down stream. He told of the old waste weirs and how sometimes they went out, flooding the lands.

* * * *

Where the Manitou Road crosses the canal, in the shadow of the high road embankment, is a lovely old brick Colonial house, full of antique furniture, that was built in 1825 by James Cromwell of New York. His grandson, Frank, lives there today.

First the Ditch cut across the Cromwell land, then the railroad and finally the trolleys. Across the canal from the house on the towpath, long ago stood the Nine Mile Grocery, nine miles from Rochester.

The Cromwells have seen the narrow boats and the mules and the horses and now the wider Ditch and the modern barges. At night their powerful searchlights flood the Cromwell grounds and the sylvan shores and the scene is a picturesque one. By day the view from the historic house so near the Erie water is equally fine. There is natural beauty along any waterway, even the man-made Barge Canal.

A mile to the east is Elm Grove, once South Greece and nicknamed "Henpeck." Once there were warehouses, two canal groceries and a blacksmith shop where canal mules and horses were shod. The "Eight Mile groceries" were operated by Mrs. Hawthorne and by John Service, Frank Cromwell recalled. Now a pleasant suburban community has grown up around the old port of "Henpeck."

* * * *

You may recall that when I rode the Long Level westward by tug in May, I told of a white house near South Greece where the canal men for years had waved to a boy and girl who lived there, had tossed them magazines and the comics, without ever learning their names.

The other day I received a letter which said:

"My brother and I are the boy and girl that the captain and co-pilot of the Matton 21 told you about. My brother is working and I will be a senior at Nazareth Academy next fall. Then I hope to go to college.

"We want you to know we have enjoyed watching and waving at the boats. We have done it ever since I can remember and we haven't forgotten about the comics and magazines, either.

"I am enclosing a letter to the captain and co-pilot. Would you please forward it to them?"

The letter was signed "Norma Amesbury."

Norma, I sent your letter on and I am sure Captain Tom and Poley Miner were delighted to get it.

And it is heart warming to know that in this modern day, the old comradeship between the boatmen and the folks on the shore has not entirely departed.

IT was a broad river and power-packed waterfalls that gave Rochester being.

But it was a narrow shallow ditch that made it great.

In her youth, Rochester incurred a debt to the Erie Canal she can never repay.

The canal pumped the life blood of commerce into the heart of a raw settlement in the mud of the river flats and transformed it almost overnight into the boom town of America, the roaring "Young Lion of the West."

The tumbling waters turned the mill wheels but the slow, steady flow of the Clinton Ditch carried the Genesee flour to the markets of the world—and made the city great.

There came a time, after many years, when Rochester, grown rich and powerful, tired of the old waterway that had nurtured the mill town in its youth, that had served so faithfully through the years of maturity. The lift bridges, attuned to the leisurely pace of the canal boats, impeded the swelling flow of downtown motor traffic in the new age of speed. Mules plodding along the Towpath past the very doors of the City Hall—what place had they in the heart of a modern city in the 20th Century

So the mules and the Towpath were banished forever and the Erie water that had wound through the city for nearly a century, was diverted into a wider, machine-dominated, less picturesque channel on the city's southern rim.

So the mules and the Towpath were banished forever and the Erie water that had wound through the city for nearly a century, was diverted into a wider, machine-dominated, less picturesque channel on the city's southern rim.

Today whining, roaring subway trains rush through the bed of the old Ditch where once the boats crawled and the mules brayed and the drivers sang and swore.

The remnants of a few old stone locks; the staunch masonry of the second Aqueduct, still in the service of the city after nearly a century; a few old buildings inseparably linked with Towpath days—they are about all the tangible remains of the old canal in Rochester.

But the intangible things, the boyhood memories, such as skating on the Aqueduct rink in winter, diving from "the hoagie bridge" at the Western Widewaters in summer—the very mention of the old canal calls them up out of Never Again Land.

There will remain always the debt Rochester can never pay and the history that the Ditch has written into the annals of the city it built out of the swamps.

* * * *

Shortly before his death in 1828, De Witt Clinton, commenting on the phenomenal growth of Rochester, then with a population of 8,000, recalled that when he passed the Genesee River with other commissioners exploring the route of the Erie Canal only 18 years before, "there was not a house where Rochester now stands."

In 1812 there were two dwellings on the 100-acre tract that the millsite conscious Marylanders, Rochester, Carroll and Fitzhugh, had bought. The population was recorded as 15 souls. But destiny, in the form of Surveyor Geddes' stakes, had marked the falls town as her own. Geddes from the first decided where the canal should cross the Genesee. A later survey, by another surveyor, placed the route 12 miles to the south, Colonel Rochester and his fellow townsmen fought that move down, and Geddes' stakes stood.

By 1815, Rochesterville's populace had grown to 331, the Red Mill had been built and was grinding Genesee wheat and the canal seemed assured. The Young Lion cub was beginning to purr.

Four years later when the route of the Ditch was definitely determined, there were more than 1,200 people living in Rochester, which had at least four flour mills. The next year the census figures were 1,500 and the contract had been awarded for the Rochester section of the canal. I am quoting the census statistics to illustrate the progress of the community as the canal became a reality.

The year of 1822 made canal history. The waterway had been completed westward to the Genesee and on October 29, the first boat laden with Rochester flour left Hill's Basin at the east side of the river for Little Falls. Rochester (the ville had been dropped) housed 4,274 people, 400 of them employed on public works, namely the Aqueduct.

"The Young Lion of the West," was roaring.

* * * *

Ten days after the opening of canal navigation in 1823 (the western section was not complete)—10,000 barrels of flour had been shipped out of Rochester. Nathaniel Rochester, going to market, basket on arm, to Buffalo Street from his Third Ward home, was meeting more and more people he did not know. Everywhere buildings were going up. The bang of the hammer, the rasp of the saw vied with the music of the falls and the grinding mill wheels. Hundreds were crossing the bridge over the river daily, the bridge at which lawmakers scoffed in 1810, asking "Who would use it, muskrats?"

That year saw the completion of the Aqueduct that was to carry the Grand Canal across the Genesee. It was the longest stone arch bridge structure in America. It was the engineering wonder of the world. It was 804 feet long with nine Roman arches. Its walls were of the red Medina sandstone obtained from the river gorge near Carthage, the rival village whose star was setting. Its coping, was of gray limestone. The whole work was thoroughly grouted, with massive iron bolts holding the masonry together. And it cost some $87,000.

That year saw the completion of the Aqueduct that was to carry the Grand Canal across the Genesee. It was the longest stone arch bridge structure in America. It was the engineering wonder of the world. It was 804 feet long with nine Roman arches. Its walls were of the red Medina sandstone obtained from the river gorge near Carthage, the rival village whose star was setting. Its coping, was of gray limestone. The whole work was thoroughly grouted, with massive iron bolts holding the masonry together. And it cost some $87,000.

Two years went into its building, with 30 convicts from Auburn Prison among its builders. One day at the end of work when the prisoners were supposed to march back to their barracks on the island now occupied by City Hall Annex, they tried to stampede the guards and escape. The plot failed. Only a half dozen escaped and all but two or three of them were rounded up in short order.

The first Aqueduct pier was carried away by river torrents and during the spring of 1823 heavy rains and snowstorms hampered the work. But at last the great engineering work was complete and the voice of the Young Lion sounded throughout the land.

But that first Aqueduct was found to leak badly. Besides it allowed passage of only one boat at a tune. The result was fights between crews for right of way and consequent delays to the traffic of the Ditch. In 19 years it was replaced by a new structure.

* * * *

A warm sun shone that June 7 of 1825. Evergreen arches hung over the streets, flags waved from buildings, children wore gay scarves and badges. Nearly 10,000 congregated at the basin west of Exchange Street.

A packet boat hove into view. Bells rang, drums rolled and cannon boomed. From the deck of the boat a thin-faced old man waved, smiling at the crowds. Marie Joseph Paul Arthur Gilbert Molier, Marquis de Lafayette, had come to Rochester on his grand tour.

There were dinners and speeches and all traffic on the canal was suspended for the day. Veterans of the Revolution shook hands with their aging general at Hoard's Tavern in Exchange Street. A tablet in the wall of the Lincoln Bank branch office today marks the site of that reception of 120 years ago.

* * * *

October 26 and 27 of that same year were red letter days, too. On the morning of the 26th men stood in the rain beside cannon lined upon the canal bank, tensely waiting, as if for an invader.

At 10:20 the silence was broken by the far thunder of cannon in the west. The men of Rochester pulled their lanyards and the guns of the "Young Lion" spoke. Soon off to the east was heard the boom of the Pittsford salute.

Governor Clinton and his flotilla had left Buffalo on the triumphal tour that marked the formal opening of the Grand Canal.

The next day found Rochester in a ferment. Throngs converged on the canal banks near Exchange Street. Eight companies of militia in showy uniforms and under arms, turned out. So did a committee of leading citizens, headed appropriately enough by Jesse Hawley, who from a debtor's prison, had penned the first clarion call for a canal across the state.

At 2 p. m. four sleek grays trotted down the Towpath. They were hauling the flagship, Seneca Chief, on which De Witt Clinton was riding the glory road. In its wake were the Superior, the Perry and the Buffalo.

At Child's Basin, the Rochester packet. "Young Lion of the West" guarded the entrance. There ensued a ceremony patterned after the Masonic ritual. Was not Clinton the Grand Master of the order? From the Seneca Chief came the ceremonial challenge. From the Young Lion came the reply: "All right, pass." The Lion gave way, the Seneca Chief slid into the basin. Then pandemonium broke loose.

The militia fired their muskets. The cannon roared again. The crowds yelled. The Rochester and Canandaigua committees took their places under an arch surmounted by an eagle and the Seneca Chief was moored amid fervid oratory.

Then came dinner at the Mansion House in State Street, more speeches, many toasts and at 7:30 that night the visitors re-embarked. With the fleet sailed the "Young Lion of the West," with a distinguished Rochester committee aboard to take part in the historic "wedding of the waters" nine days later at Sandy Hook.

* * * *

In 1825 Rochester had 4,274 inhabitants. Within a year the figure had jumped to 7,669. No other town in America was growing so rapidly. 'The Young Lion' was THE canal town, with 160 Rochester-owned boats and. 882 Rochester-owned horses on the Ditch.

One day in 1826, 22 craft arrived here, among them: The New Hampshire, out of Brockport with ashes, flour and wheat; the General Putnam with merchandise from Albany, the Brandywine bearing wheat, ashes, whisky from Buffalo; the Sea Gull, out of Salina (Syracuse), with a cargo of salt, and the Echo, from Holley, carrying wheat. As many departed with varied cargoes. That year also, 100 live rattlesnakes were shipped from Rochester for the European market. Their oil was considered valuable.

* * * *

Then came the tumultuous 1830's when Rochester's population more than doubled, jumping from 9,000 to 20,000. During that decade the 27-year long, four million dollar enlargement of the canal was begun and work was started on the second Aqueduct. Clinton's Ditch had outgrown its baby clothes.

By 1835 Rochester owned or controlled half of the boats on the canal. Hundred of canal vessels were built in yards here.

It was in 1836 that a canal boat brought to Rochester a cargo of ominous import. It was the first locomotive for the Tonawanda Railroad. The next year the first train rumbled out of the city for Attica. An interloper had arrived to challenge the supremacy of the waterway and to remain its relentless rival for many years.

* * * *

The second Aqueduct, a little to the south of the first, was begun in 1833 and completed in 1842 at a cost of about $444,000. This one did not leak. Most of it is there today, a part of the subway system. The structure, supported by seven arches, was 848 feet long and 45 feet wide to conform to the new dimensions of the Ditch. It was built of coniferous limestone, obtained at Split Rock near Syracuse.

* * * *

During the 1840's, the city's life swirled around Exchange Street and the canal. There the boats arrived and departed. There were the big hotels, the offices, warehouses and stores linked to the canal trade. To the south were lumber yards, soap and candle factories.

And there was the huge, rambling four-story Rochester House, catering to the packet trade. The packets brought sonic distinguished visitors, among them tourists, actors and statesmen. From the hotel's big balcony President Martin Van Buren and other notables of the time spoke.

It was a gaudy era and the packet boats gave it sparkle.

Edwin Scrantom, who was born in the first dwelling built on the 100-Acre Tract, on the site of the present Powers Building, gave the Historical Society when an old man this vivid picture of the arrival of a packet boat:

"A long, slim boat with its glass sides shining in the sun rounded and came into the Aqueduct, on the east side of the river. Her bow and stern, displaying ribbons and streamers, she dashes along, a thin; of life, drawn by three over-driven horses, covered with a foam of sweat.

"We can see, too, the lines of trunks along the docks on the outside and in the middle a standing congregation of gentlemen and ladies all agog, ready to see and be seen, We can hear, too, the nervous duet of two Kent bugles or maybe it band of music, heralding the incoming packet.

"The packet boat enters Child's Basin. Loafer Bridge is a mass of human beings. Handkerchiefs are displayed and answered from the boat. Cheers go up and the crowd, especially the boys, rush for the packet offices where cabmen, hackmen, porters and runners call for guests, scramble for hotels and make confusion worse confounded by their bickerings and blackguardisms."

In the 1840's a new span replaced the Loafer Bridge, so called because a character called Loafer Jim spent most of his time there, watching the boats. The new high bridge was difficult for horses and wagons to negotiate. The Rochester House burned down in 1853. It had lost much of its old elegance. Evangelists held services in its big parlor, preaching to the hard-boiled canallers. The railroads were driving the packets out of business.

A colorful era was dying and Exchange Street never was quite the same again.

* * * *

In 1852 the weighlock was built, to be part of the canal scene for 70 years until it was torn down to make room for the subway. It was on the east side of the river on Crouch's Island, about opposite Capron Street. A two-story brick- building, it had a stately portico with Doric pillars. Boats entered under this portico. Double gates at either end allowed the water to be drawn off and the tonnage taken by huge scales. Up to the time tolls were abolished in 1852, it was one of the busiest places along the Towpath.

* * * *

The great flood of St. Patrick's Day, 1865, which took such heavy toll in the city, swept away the canal banks near the river.

Three years later the first steamer ever to traverse the waterway, the Edward Backus, built here and named after her owner, a Rochester man, brought a load of coal from Ithaca. It foreshadowed the eventual passing of the Towpath and four legged motive power, although that change was many years in coming.

Rivalry was so intense captains would hire crews for their fighting prowess rather than their seamanship. There were canal bullies all along the line. Ben Streeter was the Rochester bully. He lived at the Rapids, across the Genesee from the present River Campus and mostly worked on the old Genesee Valley Canal. Ben fought the bully of Buffalo in the Reynolds Arcade for one hour and licked him. The exact date of this classic battle is elusive.

But the late Capt. H. P. Marsh, canal veteran, in his delightful little book, "Rochester and Its Early Canal Days," recalled that "not an officer dared interfere."

The craft owned by the big companies were called line boats. They were likely to hire captains of the rougher sort. The captains engaged their own crews, men after their own hearts. Many of the independent owners who piloted their own boats were respectable and, some of them, pious men. They took their families along and their boats were neat and horselike.

But in general, the Erie Canal was no place for one who believed in the niceties.

Songs floated through the night from the Towpath, robust ballads, many of which are unprintable. The canallers creeping across the state, sang as marching soldiers do, "just to pass the time away."

Here is one of the better known ballads that has survived the changing years:

The last statement is sheer "poetic license" because there were grog shops at every lock.

There's another song titled "Boatin' on a Bull-Head." It must be explained that Bull-Head boats, many of which were built in Rochester yards, were built flush up to the cabin. The helmsman had to stand on the cabin roof to steer. There was little space between his post and the low bridges. So many it canaller was swept off to his death. The old ballad warns:

* * * *

The later days of the canal were less picturesque. Politics and machinery and big combinations added materialistic touches. But when the Barge Canal was authorized in 1903 (incidentally against the violent opposition of Rochester interests) there were 4,000 boat owners on the waterway.

The burly figure of George W. Aldridge, longtime political boss of Rochester, strode the canal stage in the late 90's when he was state superintendent of public works. During his regime millions were appropriated for canal deepening and other improvements. The use of these funds was later investigated by Gov. Theodore Roosevelt who found "no cause for complaint." The horde of loyal Rochesterians who got canal jobs under Aldridge had no cause for complaint, either. Patronage fell like ripe fruit in a hail storm.

For 15 years the Barge Canal work went on. The new ditch, for 13 miles, from west of Pittsford to South Greece, skirted the city it once bisected. Some contractors made money. Some went broke. Digging the long "Rock Cut" west of the city was a heart-breaking job.

In 1912, agitation began in Rochester for abandonment of the canal bed within the city. But business interests along the route fought for its preservation. In 1919 the last boat passed through the Aqueduct. In 1920 the Ditch was declared formally abandoned.

Meanwhile, on May 10, 1918, State Engineer Williams had grabbed a shovel from a workman and opened a trench across a dike at the west bank of the river in Genesee Valley Park. Genesee water poured through to mingle with Erie water. The Barge Canal was proclaimed formally opened.

In 1921 the city authorized the electrified railroad in the old canal bed. The next year Mayor Van Zandt wielded a silver spade in the Ditch west of Oak Street. Rochester's $11,800,000 subway had been launched.

Just a century before the first flour-laden canal boat had left Hill's Basin.

* * * *

I'll bet that subway conductor still is wondering about the baldheaded guy who rode the whole length of the subway—twice in one morning.

If his passenger had told him that "I'm not really riding the subway at all. I'm riding the Erie Canal and this is not 1945 but 30, 40, 50 years ago," the conductor surely would have called the wagon.

As the subway car sped along the tracks in the bed of the Clinton Ditch, I tried to recapture the yesterdays that hold fond memories for so many Rochesterians who are no longer young.

In fancy, boys were diving again off the crossover bridge, "the Hoggie" at the Western Wildwaters; the "Old Calamity" lift bridge was up at West Avenue (West Main) and the chorus "that's why I'm late for work" came out of the past.

The little Jessie chugged along on the Fairport run, beer kegs piled high upon her deck; the C. H. Francis shuffled off for Buffalo with a mighty whistle blast that scared the farmer's horses crossing the Washington Street bridge.

Change the scene to winter and skaters were doing "the figure eight" on the Aqueduct skating rink and kids were playing "shinny" on the ice of the old canal feeder.

Canallers were buying soap and "suds" at the Adwen grocery at Lock 66 and lads were splashing merrily in the Eastern Widewaters and hitching rides from lock to lock.

A locktender and a mule driver were battling it out on the Towpath at Winton Road and the Caleys were shoeing canal mules in their blacksmith shop at the corners in old Brighton.

* * * *

Want to go along on a dream trip in a memory-haunted ditch?

Let's start at the western terminal of the subway—and forget there is such a thing. The Western Widewaters, playground for generations of West Side youths, shimmer in the sunshine as of yore.

The younger kids splash around in the "baby hole" at the shallow end, but bolder souls dive from the "Hoggie Bridge," hard by Driving Park Avenue where the Towpath crosses from the north to the south side. Mischievous boys call out "Whoa, Johnny," and the mules all stop and the drivers swear eloquently.

At the western end of the waters is Scott's Bridge, carrying Field's Road over the canal. Max Straussner of Lisbon Street works today in the huge plant of the Rochester Products Division of General Motors on the southeastern edge of the former Widewaters. He recalls a day in 1900 when he dived off Scott's Bridge, then looked back a couple of minutes later to see the span collapse. It stayed down many a year until Mount Read Boulevard was completed, skirting the whole northwest side of the city. By then, the Widewaters had been filled in and were only memory.

At Lexington Avenue, the "Slanty Roof" tavern still stands but it serves the factory trade and not thirsty canallers. Once it was Hartleben's and later Johnson's. Arthur W. Johnson of the Fire Bureau, son of Otto Johnson, once proprietor of the tavern, called up boyhood recollections of rented rowboats and small launches, manned by anglers, swarming the Widewaters on summer Sundays.

The hobo jungle in the woods to the west; the canal boats tied up for the winter and families living on them; the cinder path beloved of bicyclists; sunken barges from which kids, playing hookey from classes, dived—they are all part of the Widewaters tradition.

And the skating in winter time and the Hetzlers cutting ice. The Hetzler plant still is there and Leo Hetzler is head of the company his father established beside the Widewaters 78 years ago.

Trek north by west to Ridgeway Avenue and you see again the Four Mile Grocery, called by canal men "the hard cider stop." Years ago it vanished from the scene but the old canal banks all along the "Big Ridge" are still visible.

The canal, riding the "Big Ridge," was on higher ground than the land to the north and old timers who lived in the lower regions recall how strange it was to see moving canal boats silhouetted against the sky as they looked upward.

* * * *

"Nothing provokes so much profanity in Rochester as the canal bridges. Captains apparently wait until morning, noon and evening rushes are on to start through the waterway with their boats. Cars are blocked for street after street and pedestrians and bicyclists are equally inconvenienced."

So fumed an editorial in the Rochester Herald in 1903.

Possibly the writer had "Old Calamity" at the present intersection of West Main, Broad and Clarissa in mind.

In the 1870's there was an overhead bridge which also spanned the old Genesee Valley Canal, 300 feet away. The heavy grades necessitated the use of a hill horse for the horse street cars. Then a swing bridge came, to be supplanted by a lift bridge in 1889. The last "Old Calamity" lasted as long as the old canal did. It should have been dubbed "Old Alibi" because for years it formed a rock-ribbed excuse for being late at the office or shop.

In the 1870's there was an overhead bridge which also spanned the old Genesee Valley Canal, 300 feet away. The heavy grades necessitated the use of a hill horse for the horse street cars. Then a swing bridge came, to be supplanted by a lift bridge in 1889. The last "Old Calamity" lasted as long as the old canal did. It should have been dubbed "Old Alibi" because for years it formed a rock-ribbed excuse for being late at the office or shop.

Once it got stuck while down and would not go up for days, piling up traffic on the waterway for miles in either direction. Once "Calamity" tossed one of its weigh boxes, filled with chunks of iron, on the roof of a trolley. It was only a glancing blow and none of the passengers was hurt save those trampled in the rush for exits.

There were a lot of those lift bridges in Rochester and they, had considerable to do with the abandonment of the Ditch through the downtown section.

The Washington Street bridge was an overhead span with steep approaches that tested the power of automobiles in the infancy of the horseless carriage. A Virginia creeper twined around it.

From the old bridge the elegant ladies of the Third Ward watched for the packet boats bringing home their men from sessions of the Legislature at Albany or financial deals in New York. The old Ditch was the northern boundary of the "Ruffled Shirt" domain.

In later days, Mechanics Institute art students used to sketch around the bridge. From the Washington Street dock and warehouse, the stone building that now houses a restaurant and a religious sect, the steam freight packets used to depart for east and west.

* * * *

The time has come to talk of many things, including ships that carried shoes and sealing wax and cabbages but nary a king.

The steam freight packets ran through the 1890's up until around 1905 when the new Barge Canal had doomed the Towpath.

Maybe the names of some of the boats will evoke memories—the William B. Kirk, the C. H. Francis, the John Owens, the Charles J. Johnson, the Milton S. Price, condemned and supplanted by the Celena, the fruit boat; the O. B. Tanner, the Graham, the J. M. Wiltsie, the Whipple, the little Jessie, the Frankie Reynolds and the Rambler among them.

For their animal-powered contemporaries, the steam packet men had a contemptuous word, "Hayburners."

The packets carried all mariner of merchandise and stopped at every canal town where merchants relied on them for most of their supplies. In fall they bore away tons of produce and fruit. Storing that freight according to destination was an art. There also was a vast amount of clerical work involved in checking and making out way bills, usually the task of the captain-purser.

Harry A. Wood, 71, who lives in Rostyn Street, for ten years served the Buffalo and Rochester Transit Company in that capacity and how his eyes kindled as he looked over old pictures of the boats. He told how the girls in the Kimball factory, now City Hall Annex, would toss out tobacco to passing boatmen; how his boss, Judson Webster, co-owner of the line with Henry Chamberlin of Buffalo, rode the Towpath on his bicycle checking his boats; how the bank watchers would report pilots exceeding the speed limit, for too much speed caused swells that might wash away canal banks.

There were occasional passengers. Sometimes they paid. Sometimes they rode free. The captains did not care much. Freight was their business.

And for years the canal boats waged war with the powerful railroads that paralleled the Ditch. It was an unequal struggle. For the rail lines would lower their rates during the canal season and raise them at its close. There was no Interstate Commerce Commission or tariff regulatory body in those days.

The Webster-Chamberlin interests sold out around 1899 and some of their boats and others were operated by the Buffalo, Rochester and Syracuse line, headed by George Hall. This line gave up the ghost in 1905.

I spent some time chasing around the countryside looking up canal men, never knowing there were two canallers right in my office. One of them is Fred Masterson, the night cashier, who was captain of the C. H. Francis in 1903, and the other, his nephew, Howard Kemp, the fish and game columnist, who that year, although a mere boy, worked as a deckhand.

The Francis had a capacity of 100 tons and plied between Buffalo and Syracuse. Captain Fred recalls one time that busy fall of '03 when the crew, tired out from juggling freight at every port, found waiting them at lower Lockport 525 cases of canned goods and at upper Lockport a huge heap of iron castings and a barrel of pitch.

Sometimes the boats carried excursionists, usually to groves near Spencerport and Fairport in the days of peek-a-boo waists, picture hats and buttoned shoes.

Once the William B. Kirk, celebrated as an excursion craft, broke away from its moorings at the feeder and was swept down the river. It wound up with its bow way out over the Court Street dam. The weight of the machinery in the stern kept it from going all the way.

In the autumns of some 35 years ago University of Rochester students used to charter canal boats to take them to the Varsity-Hamilton football games at Clinton, near Utica. In 1910, among the passengers on such a trip on the good ship Rambler, were three men now connected with the Rochester school system, James M. Spinning, superintendent of schools; John M. Merrell of East High and J. Jenner Hennessy of Franklin High. Others were Frank Wells, the insurance man; Axel Gay of Eastman Kodak and Ellis Gay of East Rochester.

The Rambler stopped in Syracuse. The Students had dinner and went to a show but the crew evidently found other forms of entertainment. Let Hennessy tell the tale of the night ride to Utica:

"The Erie itself was quiet and serene but what it failed to furnish in excitement was supplied by the antics of the boat. The west-bound traffic was heavy that night. There wasn't a west bound craft that we did not meet either broadside or lead on. Along toward morning the Rambler tried to hurdle the line between a tug and a tow. Then when the westbound boats got scarce, we just rammed one bank or the other."

But the collegians reached Utica in time to see Rochester wallop Hamilton 5 to 2.

In the fall of 1919, the Towpath Era ended when Capt. Marion S. Kelsey piloted the William B. Kirk through the Aqueduct. On Dec. 2, 1927 Canaller Kelsey rode the first car to flash through the city's new $12,000,000 subway.

* * * *

Through the downtown section, busy Broad Street hides the old canal bed from view. Remember the battle over the name of the new street over the subway some 18 years ago and the determined group that fought to the last for "Towpath?"

We are underground at Exchange Street, once the core of canal activities. But in fancy we can see old Capt. Dick Patterson and his "one-man life saving station" there. Dick for years was a flagman at the lift bridge. Somehow the Towpath was never wide enough for some tavern habitues and nobody knows how many of them Dick fished out of the canal. On his shanty hung a life preserver and on his coat many medals for his rescues.

* * * *

The old Aqueduct was a gay place in the winters of the 1890's and the early days of the new century. As soon as canal navigation ended, it was made ready for outdoor skating. The rink was formed by placing sand bags at either end of the Aqueduct to retain about two feet of water in the channel. A shed was put up and a stove installed. On the stove a pail of hot water was kept at boiling point, so that skates might he clipped and cleaned of ice and snow to prevent rust.

Rocker skates with steel runners fastened to wooden tops were in vogue. Some had elaborate designs in curled steel at the toes: A few "tony" kids had skates permanently attached to boots but strap skates were the rule. There were gala nights when a band played and 10 cents admission was charged. The last trolley left at midnight and there was a hasty exodus from the rink just before the stroke of 12.

As the subway car rushed through the 100-year-old arched structure at the noon hour, in fancy I heard merry voices and saw whirling figures of other noon hours long ago. Business and professional men would gulp down sandwiches and coffee to spend the rest of their free time on the rink, to join the boys and girls in doing the outer edge" and other fancy numbers.

* * * *

The old canal feeder that ran from South Avenue to the railroad underpass north of the present River Campus also is enshrined in many memories. There many an East Side lad, among them Columnist Henry W. Clone, played "shinny" in winter, fished for bullheads and swam in long-gone summers. There they fought invading gangs from Swillburg and from the Rapids. What is now River Boulevard was a rough dirt road beside the feeder. But there was a good bicycling path and Heinie Clune remembers seeing Bert Lytell, a matinee idol of the time, fishing in the old feeder after riding a bike up from his hotel.

The Ditch was the northern boundary of the area known in other days as Swillburg, the Meigs-Clinton sector, The early German settlers there, and fine, thrifty citizens they were, kept pigs, hence the name. The canal served them well. They would get water out of the Ditch with rope and bucket. They used the silt from its bed for their gardens in isle spring and got crabs and other bait for fishing there.

Mrs. L. D. Potter of Thurston Court is one of thousands of Rochesterians to whom mention of the Erie Canal brings acute nostalgia. She spent her girlhood in a house on Broadway, a few doors from the one her grandfather, William Smith, built when he came here from Schenectady by packet boat in 1831. He and his sons after him had a boat yard near by.

She treasures girlhood memories of parents telling little girls to shun the Towpath and its rough mule drivers, and warning little boys never to swim in the canal that had claimed so many young lives; music of the German band floating across the Ditch from Swillburg on a Sunday afternoon; children waving at the Jessie from the Averill Avenue bridge and the Norwegian ship, the Viking, bound for the World's Fair at St. Louis, halted at the bridge for a little time and the whole neighborhood out to see it.

Hollyhocks nod their bright heads from the Towpath and the Heelpath, too, as the subway cars roar past old Lock 66 and one sees the stones of the old lock mingling with the concrete of the subway wall.

There stands one of the last tangible links with the old Ditch—the Adwen canal grocery. One of the last along the whole waterway to close, it ended its canal career in 1917. The first Stephen Adwen built it there a century ago—the long, low, weather-beaten building with the old fashioned blinds, now facing the high speed subway railroad as it faced the lazy Erie water for so many years.

The old building only recently passed out of the hands of the Adwen family. The third Stephen Adwen and his brother, George, were born in the place and have vivid recollections of the canallers who stopped for groceries, soap and beverages.

It's hard to find the landmark unless you walk what once was the Towpath. It's at the end of Adwen Place. Adwen Place is an extension of Rutgers Street and it is not a city throughfare. The first Adwen once owned the land all the way to Monroe Avenue. When Rutgers Street was built, the Adwen ns reserved 500 feet at the southern end. Today it is an unpaved private street with only three houses on it beside the historic grocery.

At the old lock site is the footbridge high over the subway that was built, through the efforts of Father Thomas F. Connors after the canal was abandoned, for the benefit of the children of Blessed Sacrament School who lived south of the erstwhile waterway.

And now we come to the Eastern Widewaters—"The Wides" they used to call them when Dr. Clint W. La Salle was an East Side boy in the 1880s.

A small part of the old "Wides" is preserved in the sparkling little lake variously called Lake Riley, Cobb's Hill Lake and Eastern Widewaters. I believe the last is still the official name.

The Eastern Widewaters never had the large following of their western neighbor but they had an intensely loyal one. The West Side was built rip earlier than the far East Side and Culver Road was a long way out when grandpa was a boy and the trolleys only ran to Alexander Street.

But the Eastern "Wider" outlived the rival western playground and for decades has been a mecca for skaters, swimmers and lovers of peaceful beauty.

The waters once extended as far as Colby Street, where Sam Hart had a saw mill and covered the present Armory site on which once were a motor engine factory and a boat works.

And in the days when Canterbury Road was Pacific Street, the Kondolf ice houses were there and the Kondolf ice pond covered what is now Harvard Street and adjacent area.

At the Eastern Widewaters, once the turning basin for the canal boats, stands a cairn made from stones of the first Aqueduct and placed there on the 100th anniversary, of the completion of Clinton's Ditch.

* * * *

"Eight minutes to City Hall" reads a sign on the subway station in Winton Road in Old Brighton.

Go up to the old cemetery on the hill where sleep the pioneers of Brighton Village and stand under the old trees of the pleasant street that leads to it and you are removed years in time and miles in space from City Hall and the clangor of the city.

You will see there the tomb of William C. Bloss, who in early days ran the three-story red brick tavern that stood beside the canal until the subway came and was known as Miller's and then as Sheehan's. Bloss sickened of the business and, as is recorded on the stone, dumped all the liquor from his tavern into the canal. He became a foremost temperance advocate as well as a champion of the anti-slavery and woman suffrage causes. He died in 1863.

Up there on the hill is the stately yellow brick colonial home that pioneer William Perrin built around 1828, the second oldest house in Brighton village. The oldest is the stone dwelling at 1885 East Ave. with its back to the canal that Brightonians call the "Plaster House." Perrin built that too—in the first lush days of the canal boom.

Back in 1842, Thomas Caley opened a blacksmith and wagon shop at East Avenue and Winton Road. They called it "Caley's Corner." For 103 years the Caleys have been there, three generations of them, switching to automobiles when the horse and buggy days passed. Three grandsons of Thomas Caley hold forth at the old stand, Frank, Morrill and William.

Morrill chanced to be the one I approached in my quest of Brighton lore. He was horn virtually on the bank of the canal. Morrill Caley remembers as a boy hearing the drivers singing on the Towpath. Some of them had good voices and some of them even sang hymns. He told of the high bridge that once spanned the canal at Winton Road and how boys used to slide down it on their sleds, right across East Avenue and the Central tracks, of the winter rink between the two eastern locks and the ice harvest there.

Brighton was a roaring canal town in its day with three locks and several hotels and saloons. One lock was at the present Colby Street, another called Sipple's after the grocery there, at Winton and a third, just to the east and known as Miller's. Bussey's was the hotel that is now O'Hara's; the East Avenue once was Case's and the Brighton, with its back to the old Ditch, was Madigan's. All of them knew the Erie "when it was a'raging."

But that was when Brighton, the three-lock port, was by no means, "eight minutes from City Hall."

"Rowlands. End of the line," sang out the subway man in blue.

There the subway ends but the old Ditch goes on, to join the new Barge west of Pittsford.

It is 1945 again. The dream trip is ended.

But the memories linger on.

To Next chapter

![]() To GenWeb of Monroe Co. page.

To GenWeb of Monroe Co. page.