The Sulphur Springs

The Sulphur SpringsTHE sulphur springs were known of old to the Senecas, once the rulers of this realm.

The Indians were affronted by the pungent odor that came from the springs and the brook that raced through a marshy glade but their medicine men found that "the stinking waters" had strange powers to heal the sick and refresh the weary.

At the dawn of the 19th Century, the first white men came and a few cabins rose around the sulphur springs. The settlers discovered the magic of the waters and they raised a shed-like bath house with a trough in it. People came, some from a distance, and filled their jugs with the sulphur water. Such were the humble beginnings of a famous spa.

In the budding days of the era of the "water cure," there came to the little Ontario County setlement called Sulphur Springs a young physician, a shrewd and enterprising yet intensely idealistic Vermonter, with a vision born of his deep religious faith. Dr. Henry Foster founded there a watering place and health center to which tired and suffering folk, some of them famous, from all over the world have beaten a path for nearly 100 years.

The story of the village of Clifton Springs is essentially the story of the Sanitarium and Hospital, and of benign, bearded Henry Foster. Without "The San" he fathered, there today would be no village of 1,800 clustering about its sprawling buildings and acres of parks.

The traveler approaching Clifton Springs sees in the distance a great red tower outlined against the sky. Just as its baronial tower, shorn these later days of its lofty spire, dominates the landscape, so does the Sanitarium rule the destinies of the village.

The reek of the sulphur waters still pervades the air as in the days when the Senecas quaffed them. And about "the little Saratoga" he founded and nurtured still lingers the spirit of Henry Foster, in his grave these 46 years.

* * * *

The pioneers of Sulphur Springs were Marylanders. The first, John Shekell, came in 1800 and built a log house on the east hill. He brought three Negro slaves whom he soon freed. A tavern was built as early as 1806, but when young Foster arrived on the scene in the fall of 1849, the village, which was shortly renamed Clifton Springs, comprised only the inn, a blacksmith shop and a dozen dwellings straggling along a country road.

Foster for three years had served as head of the medical department of a water cure near Utica and Out of his pay—50 cents per week per patient—had managed to save $1,000. A devout Methodist, he believed he had a Divine call to found a Christian sanitarium.

He looked at several sites and chose the sulphur springs. There was only marsh where stands the main Sanitarium building today. The doctor formed a stock company, bought 10 acres and began business with a four-story frame "water cure." He laid out the grounds with ponds, flower beds and sylvan walks, in miniature much as it is today.

Even in the early struggling years, Dr. Foster always was building for the future. In 1865 the enterprise had prospered so that a massive brick four and five-story building was dedicated. Two years later the doctor became sole owner of the property. A sizeable village had grown up around the water cure.

The doctor was no faddist. He was a practical man who kept abreast of all new medical ideas. He pioneered in mental therapy and the use of X-Rays. Physical exercise, rest, along with proper medical treatment and the baths, were the cardinal principles of his health-building creed.

Always there was the strong emphasis on the spiritual. Dr. Foster led morning prayer services and the chapel was the scene of some rousing revival meetings. He built a tabernacle where noted pulpit orators spoke and where sessions of the International Missionary Union were held. The tabernacle was torn down in 1916 to make way for the present Woodbury Hospital building.

In 1865 when an air compression treatment for the nervous system was the vogue, the big hotel near the water cure was converted into an Air Cure. There were noisy midnight dances at the hotel, to the annoyance of the patients at the Water Cure. The rival Air Cure did not last long. It ran into financial shoals and in 1872 the building burned and was never rebuilt.

As his institution prospered and changed its name to the Clifton Springs Sanitarium, Dr. Foster branched out into many fields. He operated orange groves in Florida. He conducted from 1876 to 1885 the Foster School for young women in the upper floors of the rambling brick building across the street from the main structure. Then as now the first story of the Foster Block was reserved for stores.

The doctor led in all civic endeavors, in the churches and notably in the temperance movement. After some of his employes had formed in 1877 a YMCA group in the "San" gymnasium, he built and donated the two-story brick building adjoining the Foster Block that houses the "Y" today. Clifton Springs is said to be the smallest community in the world with a YMCA branch having a paid director. The incumbent is Charles Rolfe. The "Y" building also houses the Peirce Library, the gift of Andrew Peirce, a railroad official who was a patient at the health center. He also gave the pavilion in the park at the main sulphur spring.

Another Foster dream came true in 1896 when the present imposing five-story structure was completed. It was fireproof because the doctor dreaded fires so much that he prowled nights about the old building, on the alert, to help finance the new building, the practice of endowing rooms was introduced. A subscriber on payment of $15,000 received a room and care in perpetuity. The privilege extended also to his "heirs and assigns forever" and as the years wear on this is likely to be an increasing financial problem.

In 1881, 20 years before he died, Henry Foster made out a remarkable document, a "Deed of Trust" conveying to the Clifton Springs Sanitarium Company the entire plant. He really was giving away the enterprise to which he had devoted his life, assuring only that it be managed by himself and Mrs. Foster during their lifetimes.

Under the terms of the deed, a two and one-half million dollar property today has no owner. Its control is vested in a self-perpetuating board of trustees of 13 members, five of whom are chosen by the board. The rest serve exofficio by virtue of their positions in church organizations. Several denominations are represented on the board.

Under the terms of the deed, a two and one-half million dollar property today has no owner. Its control is vested in a self-perpetuating board of trustees of 13 members, five of whom are chosen by the board. The rest serve exofficio by virtue of their positions in church organizations. Several denominations are represented on the board.

The document also assured reduced rates at the Sanitarium for missionaries and their families, ministers and their families, school teachers and indigent church members. These provisions are still being carried out. Any profits made by the institution "go hack into the business."

The closing words of the "Deed of Trust" are significant: "If it shall happen that the Sanitarium, in its management, shall be diverted from the spirit and the letter of this instrument or shall be prostituted to private and selfish interests, it shall be the duty of the trustees to close the institution, sell the property . . . and divide the amount received therefrom, together with the endowment funds . . . equally among the several missionary societies of the board of trustees."

Doctor Foster looked far into the future. He was determined that the enterprise which was his life work should always follow the paths he had charted for it so long ago.

* * * *

The "San's" paternalistic control of the village has often been manifested. When the Rochester & Eastern interurban electric line planned to enter the village. Dr. Foster made it plain he wanted no trolleys whining past his Sanitarium and the village bowed to his desires.

The doctor did not want industries in his village either and Clifton Springs has never been a factory town. Its only industries today are a concern that makes telephone cord and the Morris Fngineering Company that manufactures sprayers and airplane parts and is operated by Isaac A. Morris, a World War II flying veteran.

And when in the wartime year of 1918, it was proposed ro lease the Sanitarium to the government for the care of soldiers, such a flood of petitions poured in from Clifton Springs to the Board of Trustees in New York that the idea was abandoned.

"The San" is big business although it "belongs to no one." It employs some 300 men and women. The majority of the people who live in the neat homes in the village of many hills work there. There were dark days around the Spa in the great depression.

The whole village economy revolves about the health center. As Max B. Lindner, village clerk and assistant business manager of the Sanitarium, aptly put it: "Most communities have to support their hospital. Here the hospital supports the community."

The village Rotary Club meets at "The San" and its big gym houses many community gatherings.

The Clifton Springs setup is unique in that under one roof is a combined hospital, spa and hotel. Today the emphasis is on the hospital. The company owns 100 acres, including a golf course and two farms that supply produce for the institution.

What famous figures have walked through the dignified, high ceilinged lobby of the "San." Among them have been Mrs. Theodore Roosevelt, who came as a guest when her grandchild, Kermit's daughter, was a patient; Jan Masaryk, the Czech statesman; Madame Frances Perkins, Maude Ballington Booth of the Salvation Army; Dr. John R. Mott. the world leader of the YMCA; Ida M. Tarbell, the writer who "exposed" Standard Oil; and many more.

* * * *

Clifton Springs is on the Auburn Road of the New York Central and on the Lehigh Valley whose regal Black Diamond Express stops there, because of "The San."

It was the Auhurn Road that hauled the private car of Stephen A. Douglas when he came to Clifton Springs on Sept. 15, 1860 as a candidate for the presidency against Abraham Lincoln. He addressed 6,000 persons in the park at the main spring. "The Little Giant" was no stranger to the community. He had been a student in Canandaigua Academy from 1831 to '33. His mother, whose second husband was Gahazi Granger, lived near Clifton Springs and his sister, Mrs. Sarah Douglas Granger. who married Gahazi's son, was the village's first woman postmaster. She owed her appointment to Southern senators favorable to her brother. H. F. Sherwood of the Eastman Kodak Research laboratories in Rochester possesses a letter written by Douglas to his niece, Adelaide Granger of Clifton Springs, May 30, 1869, in which the statesman discussed the efficacy of sulphur and charcoal pills to combat cholera. He cautioned his niece not to have this cure published in the newspapers because then "the whole world would go to the springs. You would have people enough there in a short time to drink the little stinking creek dry and then what would you do for sulphur water?"

P. Arklcy Kemp, retired editor of The Press, cited the longevity of residents of the "health village," recalling that several years ago when Mrs. Kemp organized a party for couples married 50 years or more, 17 couples came. The party was held in the Methodist Church and the chief speaker was Father O'Brien, the Catholic priest. Religious harmony is a hallmark of this village.

Clifton Springs is in two townships, mostly in Manchester, a segment in Phelps. It is more cosmopolitan than most and has a decided cultural tone, probably because it has seen so many distinguished people and it has so large a professional class.

It is an orderly, unruffled sort of a village—and "The San" is the orbit about which it revolves—all of which is just as the good Dr. Foster planned it long ago.

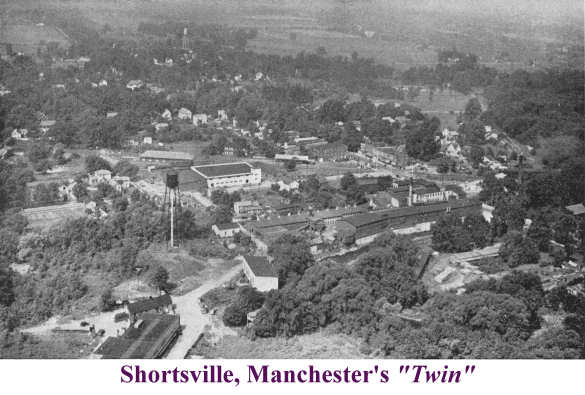

ON the old Stage Coach Road from Canandaigua to Palmyra, between the lakes and the drumlins, are the "twin villages," Manchester and Shortsville.

Both are in the Ontario County township of Manchester; their population is about the same, roughly 7,400; although the highway signs put them one mile apart, their outskirts really merge.

But they are not "two peas in a pod." Like many human twins, they have personalities that are markedly dissimilar.

Manchester, with its acres of smoky yards, its huge freight transfer, once the largest in the world; its car shops, is essentially a railroad town, a principality of the Lehigh Valley. Its economy is based as irrevocably on its railroad installations as that of its neighbor, Clifton Springs, is upon its Sanitarium.

Shortsville's destinies are not tied to the chariot of any one enterprise. It has several industries, important ones. Its tempo is steady and calm. It used to call itself "The Parlor Village."

Once rivalry between the twins was intense. The Twin Cities Lions Club, made up of residents of both communities, has done much to break down the old barriers.

* * * *

Manchester is the older twin. Its site was the head of navigation on the Canandaigua Lake Outlet, the waterway by which many pioneers came to the new land by flatboat. In 1788 a road was built from Canandaigua but it was not until 1793 that settlement began at what is now Manchester. Jacob Gillet built the first log house near the present Baptist Church.

In 1821 when a new township was cut off from Farrnington, it was called Burt. The next year it was renamed Manchester because the pioneers envisioned on the banks of the Outlet another manufacturing center like the Manchester in old England and the one in New Hampshire. In early times there was a large woolen mill, and flour and saw mills there. They languished and Manchester remained a rural trading center until 1892 when the rails of the Lehigh Valley were laid through the town.

In 1821 when a new township was cut off from Farrnington, it was called Burt. The next year it was renamed Manchester because the pioneers envisioned on the banks of the Outlet another manufacturing center like the Manchester in old England and the one in New Hampshire. In early times there was a large woolen mill, and flour and saw mills there. They languished and Manchester remained a rural trading center until 1892 when the rails of the Lehigh Valley were laid through the town.

Manchester was lifted out of the ordinary run of villages when the railroad picked it, because of its geographical location, as the site of a freight transfer point. When Manchester Transfer was opened on Feb. 2, 1914, it was the largest in the world. It still is one of the biggest and along with the classification yards, the engine house and car shops, makes Manchester a bustling railroad center. The yards cover 400 acres and the railroad employs a total of more than 500 workers. Most of Manchester's residents work for the Lehigh. The village's only other industry is a canning factory.

At the railroad transfer there are four island platforms, connected by a transverse platform, 39 feet wide. Between these platforms is trackage to hold 244 cars. Freight loaded in New York City and Philadelphia in the afternoon reaches Manchester the next day.

Manchester no longer occupies its once proud place in the Lehigh realm. Once it was the Buffalo Division terminus, a position lost to Sayre, Pa. Increasing use of motor trucks and other factors have cut the freight transfer volume although from 75 to 100 cars are handled daily and Manchester is a busy place 24 hours a day. There are car shops and an ice house of 10,000 tons capacity.

The railroad brought to the village people of many nationalities. The Syrian and Italians form the largest groups. The community has assimilated them all in democratic fashion and on the roster of the volunteer fire department which is Manchester's pride and which captures so many convention trophies for its smart appearance, are names representative of many lands.

* * * *

The Mormon Church was born in the town of Manchester although Palmyra in Wayne County is associated in the popular mind with the founding of the sect. The sacred hill Cumorrah where, according to Mormon belief, the golden plates of Joseph Smith's wondrous vision were discovered, is in the town of Manchester and in Ontario County, just over the Wayne County line.

The railroad town of Manchester on Aug. 25, 1911, was the scene of one of Western New York's most terrible railroad disasters. An eastbound train, heavily laden with delegates and visitors homeward bound from the national GAR encampment in Rochester, hit an imperfect rail, on the bridge over the Canandaigua Outlet east of Manchester. Two of the coaches plunged 45 feet down into the stream. The toll was 29 killed and 74 hurt. Only one Civil War veteran was among the dead.

* * * *

In the year of 1804, young New England-born Theophilus Swift built 11 flour mill and a grist mill on the Outlet. The settlement that grew up around the mills was called first Short's Mills and then Shortsville.

The village had industrial significance from its inception. There were early paper mills, a woolen mill and a distillery. In 1850 the Empire Drill Works, makers of agricultural implements, began operations. In 1909 the plant was taken over by the Papec Manufacturing Company. PAPEC stands for "power and pneumatic ensilage cutters." For a time they were the sole product but now Papec also makes hammermills, forage harvesters and corn harvesters. The rambling red factory, perched above the Outlet which flows picturesquely through the heart of the village, is a flourishing industry, employing some 200 hands from all over the region.

The village had industrial significance from its inception. There were early paper mills, a woolen mill and a distillery. In 1850 the Empire Drill Works, makers of agricultural implements, began operations. In 1909 the plant was taken over by the Papec Manufacturing Company. PAPEC stands for "power and pneumatic ensilage cutters." For a time they were the sole product but now Papec also makes hammermills, forage harvesters and corn harvesters. The rambling red factory, perched above the Outlet which flows picturesquely through the heart of the village, is a flourishing industry, employing some 200 hands from all over the region.

Also beside the Outlet on the site where the first paper mill was built in 1817, the Grand Paper & Bag Company carries on the Shortsville paper-making tradition. The village also has a sauerkraut plant of the Empire State Pickling Company and the M & B tinplating plant, and on the road to Canandaigua the Pioneer Threshing Conipuny makes threshers where in pre-gasoline buggy days carriage wheels were made.

Probably the average traveler knows Manchester better than he does its twin. Manchester is on the tourist route to the Finger Lakes region and Shortsville on the once busy Canandaigua-Palmyra highway, in the long ago a toll road, is a little off the beaten path today.

Those who visit Shortsville will find a wholesome combination of industrial and residential village, a trading center for a productive farm area. They will find shaded streets lined with comfortable homes. Most of its residents are of Anglo-Saxon stock and many of them stem from the pioneers.

South of the village on the road to Canandaigua is a little cemetery where the headstones under the trees are old and weather-beaten. There many of the early settlers are buried. On some of the stones are unusual epitaphs that testify to the hazards of frontier life. One such on the stone that marks the last resting place of Timothy Ryan who passed away on May 12, 1814, reads:

Another verse records the equally grim fate of Miron Aldrich who departed this life in 1819 at the age of 5:

A native son who became eminent in his chosen field is the Rev. Dr. Mitchell M. Bronk of Philadelphia, clergyman, author and religious editor now 85 years old. Some years ago he wrote a little book titled "Manchester Boys," in which he put on paper nostalgic memories of his boyhood days. A map and sketches in the book show the favorite haunts of his youth—such as "the fort, the woods, the swamp, the Outlet."

For 63 years a member of the Perry family has been at the helm of the Shortsville and Manchester Enterprise. Frank W. Perry was the first. After his death in 1908, his son, Earl F., took over. Now Earl's son, Donald, third of the line, is his father's aide in the brick office just off Shortsville's Main Street, where the twin villages' weekly is published.

Shortsville's crowning pride is its high school hand—and with good reason. In a student body of only 300, a 60-piece band has been assembled each year. Twice it won the championship of its class in national competition. The village raised $1,200 in a day and a half to send the boys and girls to the Atlantic City finals. The band won its other crown at the New York World's Fair. It also has been judged tops in state competitions.

For a decade now music has been emphasized in the Shortsvillc High School. Every pupil above the fifth grade is given a choice of musical instrument and every incentive to master it. The result has been triumphs on the national stage.

Incidentally, the director of the band bears the musical name of Edward G. Timbrell.

To Next chapter

![]() To GenWeb of Monroe Co. page.

To GenWeb of Monroe Co. page.