Stagecoach Towns

by Arch Merrill

CHAPTER ILLUSTRATIONS BY

BOB MEAGHER

PRINTED 1947 BY

LOUIS HEINDL & SON

ROCHESTER, N. Y.

FOREWORD

To the friendly people of "The Stage Coach Towns" this book is dedicated, I talked with them in their offices, their homes and their gardens and on their front porches and they graciously shared with me their memories and the lore of the communities in which they have such loyal pride.

In five years of rambling, through the Genesee Valley, the Lakes Country, the Ridge and the shoreline of Lake Ontario, in the canal towns along the old Towpath, in Rochester, the hub of the whole region, I have found the same fine cordial spirit.

"I was a stranger and ye took me in." That I shall always ays remember.

OTHER BOOKS BY THE AUTHOR

A RIVER RAMBLE

THE LAKES COUNTRY

THE RIDGE

THE TOWPATH

ROCHESTER SKETCH BOOK

Stage Setting

Stage Setting

"HERE comes the bus."

We saw it in the distance, sleek and shining, rolling down the shady village street, a monarch of the highway to which the other traffic gave respectful elbow room.

The driver sounded an imperious blast of the horn as he pulled up, with something of a flourish, before the tavern (or it might have been the drug store or gas station or restaurant) that was the village bus depot and ticket office.

The village? It might have been Churchville or Perry or Wayland or Victor or any one of a dozen others.

The coming of the bus caused only a slight flurry in the town. A few travelers with bundles alighted. A few travelers with bundles got on. Among them was this seeker after regional lore, whose 1947 assignment was visiting—by motor bus—a score of communities scattered over six western New York counties.

A century ago I would have covered that same territory by stage coach. But is not the motor bus the modern counterpart of the stage coach of long ago?

In that same old village, perhaps at that same old inn, in the bygone time, other waiting travelers had heard the distant blast of the stage coach horn, more silvery music than any bus signal. Sometimes the number of toots told the innkeeper how many guests to expect.

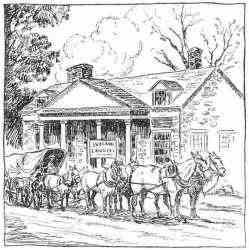

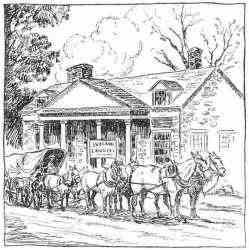

That old stage coach did not roll swiftly down the village street as does its gasoline-driven, rubber-tired successor. Still there was more drama in its approach. It was a clumsy vehicle, by modern standards, with an elliptical box-like body resting on longitudinal leather springs. It was drawn by four horses, two abreast. The village street was not the smooth paved thoroughfare of today. It was a quagmire in the spring, a dust bowl in the summer and rough at any season.

The interior seating capacity of most coaches was 12 persons, two of whom sat beside the driver. As many more squatted on the luggage on the coach top. When the vehicle became mired, as often happened, all hands got out and put their shoulders to the wheel.

The coming of the stage was an event in any village. It brought the mail, the news of the outside world and all kinds of passengers; politicos ready to talk issues at the drop of a beaver hat; business men in broadcloth, backwoodsmen in homespun, an occasional British globetrotter "slumming" in crude young America; itinerant evangelists, fancy women and concert singers; adventurers and emigrants bound for the West.

The driver, cracking his long whip, pulled up with a flourish no man at the wheel of a machine can hope to achieve. On a swank line, the driver and the postboy would be in brilliant livery.

The stage coach did not pick up passengers and hurry on, as does the motor coach. It tarried at the tavern, sometimes overnight. Men and beasts had to eat, drink and rest. There might he a change of horses and drivers. Fifteen miles was the average run.

Some of those old stage coach inns still stand. They are of frame, of brick, a few of cobblestone. Some have noble pillars and green blinds. Nearly all have the "sunbursts" or fan windows in their upper stories.

In those old Inns, in the olden days, there would be brave tall: and merry song by the glow of the great fireplaces, in the candlelight. In the event of an overnight stop, mine host would bring out the warming pans filled with live coals, that his guests might sleep in comfort.

All of which is a far cry from riding a motor bus in this year of 1947. Yet I was following the sarne old trails, stopping, in the same old towns, as had the stage coaches of yesteryear.

And making connections by motor bus over several lines in a widely scattered territory has its difficulties, I discovered, even in this atomic age.

At that it's simpler traveling than it was in May, 1830, when an advertisement in the Dansville Village Chronicle announced the "opening of a daily line of Mail Coaches between Owego and Rochester, with superior Coaches and horses, careful Drivers and everything for the accommodation of the public."

That line left Owego each day at 2 o'clock in the morning, passing through Elmira, Painted Post, Cohocton, Dansville and Genesco on its way to Rochester. The line boasted that it made the trip in TWO DAYS.

At Bath there was a connection thrice a week with stages for Hornellsville and Olean Point and also one at Geneseo three days a week with a line that ran to Buffalo via Moscow (now Leicester), Perry and Warsaw.

The promoters stated that "the line runs through a fine, healthy and cultivated country." The statement is just as true today as it was in 1830.

* * * *

But this is not just a story about stage coaches. The era of the coaches, picturesque as it was, was only one square in the colorful patchwork of the region's past.

History was written along these trails long before ever a stage coach horn echoed over hill and vale.

Most of the stage coach routes had been old Indian trails that knew the moccasined feet of the Senecas, proud Keepers of the Western Door of the Iroquois Long House, when all this land was theirs. On those trails, often on the sites of populous communities today, the Red Man built his villages and his forts, beside the waterways that still bear the musical old Indian names: The Oatka, the Tonawanda, the Canaseraga, the Conhocton, the Canisteo, the Ganargua, the Honeoye, the Irondequoit.

As Lydia Huntley Sigourney, the Connecticut poetess who was an early champion of the tribes, wrote:

- "Their name is on your waters,

- Ye shall not wash it out."

After the Sullivan expedition in the War of the Revolution had routed the Senecas from their old empire and opened the Genesee Country to settlement, the white men came down the Indian trails.

There were aristocratic land speculators and their agents, in carriages and on horseback, men of the stripe of Charles Williamson, Nathaniel Rochester, Herman Le Roy, Oliver Phelps, Nathaniel Gorham, Joseph Ellicott and many others whose names are perpetuated in the names of our towns today.

But mostly it was the humble pioneer who came to the new land. Many came on foot, carrying an ax and a gun—and little cash. They came in ox carts, in Conestoga wagons. They made little clearings in the woods and slowly reared their log cabins. Beside the rushing waters that turned the mill wheels, little clusers of cabins arose. Then came a school and always a church.

Such were the beginnings of most of the Stage Coach Towns of this tale. There were exceptions. Bath and Batavia for instance, had more grandiose beginnings. They were picked as the seats of two great land companies and they were laid out as future cities of the Genesee Country.

The forests went down, the swamps were cleared, the howl of the wolves was stilled. No longer was this "The Great Western Wilderness." The canals came and the steamboats and then the Iron Horse and the horn of the stage coach was forever inured.

The pioneers are gone. They are part of the earth they cleared and conquered long ago. But they left a rich heritage, the pioneering spirit that has never been quenched in the Stage Coach Towns.

* * * *

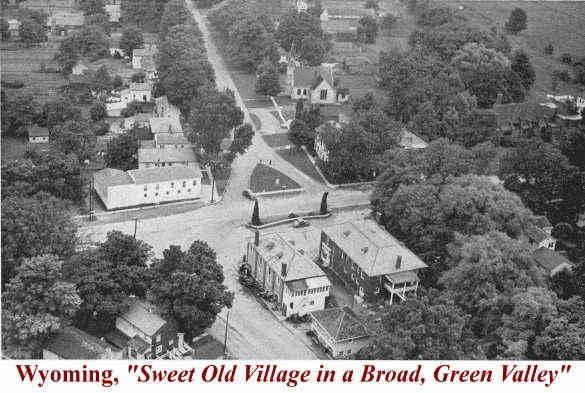

My bus tour was one of ever changing landscape. The old stage coach trails led through level country on the north, with the foothills climbing ever higher as the roads wend southward until they reach the towering hills that any other people would call mountains.

All this many-sided countryside is part of the old Genesee Country and Rochester, younger than any of the towns, is its metropolis, the hub from which the busy highways fan out east and west and south today.

These stage coach towns at the borders of the Genesee Country are as rich in history and lore as they are in natural charm.

* * * *

I found more than history and lore in this land. I. found a way of life.

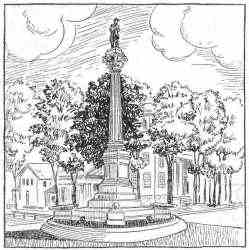

It is the land of the familiar things. It is the land of the maple tree, of the robin, of the goldenrod, of the lilac bush before the door. It is the land of the wide front porch where people sit in the twilight; of the war memorial in the public square; of the pure maple syrup on the buckwheat cakes, of the thick cream in the coffee; of the big central school, of the shiny fire fighting apparatus.

It is the land of the hunter, the fisherman, the tanned cheeks, and the outdoor life. It is the land of the folksy, unhurried ways where all are neighbors and the stranger is made to feel at home. It is the land of the fierce local pride and the community spirit.

I found in the "hinterland" a well informed people. Perhaps they take more time to read and to think than do city folks who are forever dashing hither and thither, racing against the hands of the clock.

It is the same in the Valley of the Genesee, in the Lakes Country, along the Ridge and the old canal.

For this Western New York of ours is more than a geographical region. It is a way of life, a way that is genuine and good and so American!

Down the Buffalo Road

Down the Buffalo Road

REMEMBER how when we were kids we used to play games that always started with the words "Let's Pretend"?

Let's pretend that the hands of the clock have slipped back more than a century and that we are riding for a little while in a stage coach, drawn by four spirited horses, down the road that links the booming young cities of Rochester and Buffalo.

It's a rather cramped journey. The passengers who got on at the Mansion House at State and Market Streets in Rochester till all four crosswise seats of the coach. It's a bumpy ride, for the roads are full of pitchholes. But it is a fine spring day and the fields and woods all along the Buffalo Road are fresh and green. We are young in a young America that is not used to case and luxury.

With strident blast of coach horn, we pull up before a two-story brick tavern where Union Street joins the Buffalo Road at North Chili. That tavern is a favorite stop for the drovers on their way to the Rochester market, only eight miles away. There they feed and water their cattle, swine and sheep. They find their own refreshment in the tap room.

North Chili in those days was a self-sufficient community with stores and mills. Its farmers bred fine road horses and cattle. That was before the first railroad train crawled through Chili town in 1837 on its way from Rochester to Batavia while the fences all along the line were packed with spectators. Today that pioneer railroad is part of the Main Line of the imperial New York Central.

They were gay times in the tavern, dances in the ball room, band concerts from the double-tier porch that faced the Buffalo Road. But there were those in the neighborhood who shunned such frivolity. They were the New Englanders who built the white churches—and their sons and daughters who were firm in the faith of the Puritans.

Stage coach days were done but the tavern was there when in 1866 the determined leader of a religious denomination came to North Chili, seeking a location for a church school.

He was Bishop Benjamin Titus Roberts of the Free Methodist Church. In 1858, after he had challenged some dogmas of the Methodist Episcopal Church of which he was a pastor, he had been ousted at a stormy session of the Genesee Conference at Perry. He was an arch fundamentalist and he found many followers. Out of his expulsion grew the Free Methodist Church of which he was the first bishop. Soon there were branches of the sect in many Western New York villages.

Bishop Roberts felt the need of a college for his growing church. He liked the North Chili location, rural yet not isolated. But there was a tavern in the town and he wanted no such influences around his Christian school. So when he bought a plot of land for a campus nearby, he also bought the tavern—and promptly closed it.

Before the first building was erected on the new campus, the four-man faculty of Chili Seminary held classes for the student body of 24 in the erstwhile tavern, shorn of its bar and bereft of its music.

Thus the first Free Methodist educational institution in America was born in a tavern.

* * * *

Today that school is the Roberts Junior College, one of six Free Methodist schools in the nation. There are imposing buildings on the emerald campus, well back from the highway. Members of the church have been generous givers. One such benefactor, to the tune of $30,000, was A. M. Chesbrough and from 1884 to 1945 the school bore his name. On its elevation to junior college rank, the name was changed to honor its founder.

Roberts College has 297 students, about evenly divided between men and women. About half come from the region, the rest from four seaboard states and New England, comprising the Eastern Conference of the church. Sixty former service men are enrolled under the GI Bill of Rights plan. The 13 apartment units for married couples are filled. Many students "earn while they learn." Some work on the 300-acre dairy farm owned by the college.

The school has never deviated from the tenets stated in its first catalog in 1869 which described Chili Seminary as a place "where practical and thorough education can he gained without the hindrances to piety found in many of the fashionable schools of the land."

The most recent catalog, under the heading, "standards of life," warns that: "The registration of students known to use tobacco or alcoholic liquors or beer will not be accepted and use of them while in attendance will subject the student to dismissal ... students from abroad are required to refrain from participating in card playing, dancing, attendance at theaters, including motion picture theaters, and attending meetings of secret societies.... Modesty and conservatism in dress are required at all times. Decorative jewelry is out of harmony with Roberts standards."

If you think these regulations have made Roberts students a repressed and downcast lot, you're mistaken. The young faces I saw on the campus were happy ones. There is a wholesome, refreshing air about this 80-year-old college amid its sprawling green acres on the old stage coach road to Buffalo.

Incidentally, the tavern building in which it was born, still stands. For years it was the village postoftice. Now it is a private residence.

Chili, settled in 1792 and carved from Riga into a township in 1822, was part of the "Mill Seat Tract," successively owned by the Seneca Indians, Phelps and Gorham, Robert Morris and the British Pulieney interests. Its name probably is a corruption of that of the South American republic, Chile. The pioneers were wont to fasten foreign names on their settlements, then sometimes misspell them and often mispronounce them.

* * * *

And now westward on the old highroad. Far above a village under a green tent of trees cluster the church spires. The casual traveler sees the road sign, "Churchville," notes the spires and leaps to the false conclusion that: "This village was so named because it had so many churches.

Its name honors Samuel Church, its first settler, who came in 1806 and built the first saw mill beside the sinuous waters of Black Creek. He was a New Englander, as were most of his fellow pioneers.

The village they founded, with its picturesque mill dam in its heart, its many white houses and well groomed lawns, today retains more than a trace of its Yankee ancestry. There are so many descendants of the early settlers and so many generations of the same family have lived on the same acres. Yet strangers who have come to dwell in the pleasant village at Monroe County's western border have found a friendly acceptance.

Churchville became an early trading center and outstripped its older neighbor to the south, Riga Center, because the waters of Black Creek turned mill wheels and because it was on the line of what became the New York Central Railroad.

Around the mill dam in their time have stood saw mills, a factory that made cutting boxes for chopping fodder by hand; a three-story planning mill. Today Churchvi11e is almost wholly a residential village.

Many of her 601 inhabitants (1940 census) work in Rochester, 15 miles to the eastward. Once many commuted by New York Central train. Now the passenger trains roar through without even hesitating.

On Sept. 28, 1839, in a two-and-one-half-story brick house on Churchville's South Main Street, a daughter was born to Josiah Willard, a cabinet maker, and his wife, Mary Hill, The baby was named Frances Elizabeth. She came from Yankee and pioneer stock on both sides.

Today in front of the same house, now half hidden behind a store, a historical marker proclaims the birthplace of Frances E. Willard, a founder and for 19 years president of the Women's Christian Temperance Union, one of the world's most famous women.

Frances left Churchville with her parents for Ohio at the age of 2, but during her lifetime she made many visits to her kin in the neihborhood. In 1867 she brought her dying father back to the scenes of his boyhood and for months hovered near his bedside, often singing hymns to him In her soft, sweet voice. Churchville last saw its famous daughter alive in 1897 when she paid a visit to an aged aunt.

On Feb. 21, 1898, Frances Willard came back to her native village—in a flower-decked casket. The temperance leader had died in New York four days before. The special train bearing her west for burial in Evanston, Ill., stopped a whole day in Churchville. There was a memorial service in the Congregational Church which was packed to the doors.

On the 100th anniversary of Miss Willard's birth, Sept. 28, 1939, more than 1,000 delegates to the WTU national convention being held in Rochester made a pilgrimage to their leader's old home, in a cavalcade of 52 buses. At the exact hour of her birth, the Churchville High School Band struck up "Onward Christian Soldiers," the battle hymn of the WCTU, and the eulogies began, from a flag-decked platform on which sat such noted white ribboners as Mrs. Ella Boole and Mrs. D. Leigh Colvin.

It was a red letter day in the village's history.

Churchville is in the town of Riga which for some years was the only one in Monroe County to vote "dry" under local option. But today one can buy legal beverages—as well as excellent food—from it hotel squarely across the street from the house in which the leader of the WCTU was horn.

There is a pretty little park in the business center. It contains, a stone marker to the memory of Miss Willard, a drinking fountain and a memorial to John C. Newman, long a Churchville merchant. His son, Floyd, made possible the purchase of the park by the village.

* * * *

Chipper, razor-keen Edmund S. Parnell is in his 91st year. He has lived all his life in the vicinity and for 64 years kept, first a general store and later a drug store, in the village. In the sitting room of the house to which he brought his bride in 1893 and where they have lived ever since, he drew on his rich fund of village memories.

When he was a little lad, he saw the train pass through that took Abraham Lincoln to Washington for his first inauguration and four years later saw the funeral train that bore the slain president back to Illinois. He spoke of the imposing three-story hotel with the Mansard roof that was built in 1864 on the present village park site, with its huge ball room, its "ladies' and gents' sitting rooms," its enormous barn and the traveling shows that exhibited there. He remembered the rich New Yorker who built the hostelry, Hanford Smith, sitting on its rambling porch in his plug hat, and the fire of 1882 that razed the Smith House.

There were memories of the old pump before the hotel and the Liberty Pole opposite; of the Walton House, another big hotel near the depot that burned about 1910; memories of waiting on Frances Willard, a gracious lady, in his store; of Dr. Craig, the village physician who was the father of Dr. Marion Craig Putter of Rochester.

* * * *

To the pioneers Black Creek was a source of water power. To their descendants it has been a play spot. Willard Randall, the village clerk and historian, told—with nostalgia in his voice—of the old, swimming hole at the great elm, now wrecked by storms, and how small boys would grab the rope, with a knot in it, that was suspended from a limb and would swing far out over the water before they dived. That same creek was their skating rink in the winters of yesteryear.

Along the creek north of the village are a dozen cottages, mainly those of city folk. The present generation of Monroe County folk knows Black Creek well as the stream that winds through the 432-acre Churchville County Park, with its golf course, picnic areas and sylvan woods.

Picturesque names are Indian Hill and Pathfinder Spring. When the first white settlers came, they found an Indian encampment on Dewey Road, north east of the village and the site, now on the farm of Samuel Way, has since been called Indian Hill. It was there that the grandparents of Frances Willard settled in 1816, pioneers on the land," as the historical marker says. Some years ago an Indian burial mound nearby yielded many relics and farmers' plows still uncover arrowheads in the neighborhood.

From Indian Hill a footpath leads to the Pathfinder Spring. There from time immemorial cold, pure water has bubbled out of the earth along McIntosh Road and near the present golf course. Today it is the source of the village's water supply. Some 30 years ago a company was organized to bottle Pathfinder Spring water which was shipped to nearby cities. The building that houses the spring is full of bottling machinery and other reminders of that short-lived enterprise.

A showplace is the pillared mansion at Hilltop, the big dairy farm at the village's southern edge. It was built in 1905 by William L. Ormrod, onetime hotel man in the South who married a Churchville woman and established a country estate which he stocked with pure-blooded Jersey cattle. He served two terms as state senator (1912-16) . Hilltop now is the property of Delancey N. Boice, who raises thoroughbred Brown Swiss cattle and not long ago set a precedent by shipping some of his young stock by air to South America.

William D. Kearney, the village barber, is so popular that four times he was elected supervisor on the Democratic ticket in a Republican stronghold. Two years ago he lost, but by a narrow margin. When I asked the secret of Bill's vote-getting powers, the answer was simple: "Because he is such a darn swell fellow."

As before stated, Churchville is not an industrial town. But it has one most unusual industry, "a canary factory," in other words, the aviary of the R. T. French Co. of Rochester. The firm makes bird seed so its canary breeding and distributing business is entirely logical. Before World War II, the company took over a former paper box factory in the village. The war stopped shipments from abroad and soon there were hundreds of birds twittering in their tiers of cages in the air-conditioned plant which has an automatic watering system. Once an automatic feeding system was given a trial. Canaries are shipped out of Churchviile to all parts of the country, in ventilated containers, each containing half an orange for liquid diet and plenty of bird seed for solid food in transit. Recently 375 canaries, were flown to Churchville from Norway.

* * * *

Drowsing on its hilltop, dreaming of its colorful past is Riga Center. New Englanders, recruited by the first Janes Wadsworth, settled there around 1805. The town was called West Pulteney before it was renamed after a Russian city. It was a thriving center in early days, a stage coach stop on the Canandaigua-Batavia line when Rochester was nothing.

The village green, flanked by a white church and a now abandoned school, tell of Riga's past consequence. Two historic buildings stand at the crossroads, now so quiet. They go back to stage coach days. One was built as an inn in 1808. It was the first frame building in Riga and the first postoffice. Five generations of the Adams family have lived there. When Mrs. Willard Adams, the wife of the present owner, pointed out the big fireplace with the old fashioned bake ovens, the room that was once the bar and the room that was once the postoffice, stage coach days lived again for a moment.

Across the road is a massive, two-story gray brick house with the graceful doorway and many paned windows of the pioneer time. It was built in 1811, also as an inn. For several years after 1846 it was the Riga Academy, a school for boarding and day pupils. After the academy gave up the ghost, part of the building was torn down and the great hand-hewn timbers, some of them a foot and a half thick, went into many a neighborhood barn.

To that house, after the Civil War, came Col. Frastus Ide, a gentleman of Maryland. He lived in the grand manner and his stable of blooded horses was his pride. After the death of the colonel and his wife, their daughters, Lily and Clara, rather eccentric spinsters, lived in the mansion. They shared their father's love for good horseflesh—and for all dumb animals.

Lily died and Clara went to live in California, leaving behind

her beloved sorrel horse, Ivan. Before she died, Clara wrote this unusual clause in her last will:

"I will and direct that my horse Ivan shall always be kept on my farm in Riga and he shall not do any work as long as he lives and shall when dead be buried by the side of the deceased horse, Bizzy, on the southeast corner of the woods on my farm and the place of burial of both horses shall, never be plowed."

A young Rochester couple, Arthur and Mary Cowles, recently took over the historic house, which has a fireplace in nearly every room, exquisite white mantels and white woodwork. They have ripped away the bricks that concealed the old basement fireplace with its crane and hook for the kettle. How I envy theirs their "dream house" in the country.

* * * *

Bergen is only three miles from Churchville. It is about the same size. It is a little older with the same Yankee background, but between the two villages stretches a county line and in York State that can be quite a gulf.

Bergen is just over the line in the old County of Genesee. The average tourist never sees the village because the principal highway from Rochester to Batavia, and Buffalo, now skirts it to the south.

The first settler was Samuel Lincoln, in 1801. The town, named, for no known reason, after a Norwegian city, was part of the Triangle Tract sold by Robert Morris to Herman Le Roy and associates and was cut off from Batavia in 1812.

There's a story that two of the early settlers, the Leach brothers, Solomon and Levi, traded wives. Levi gave Solomon five gallons of whisky "to boot." But in two weeks Solomon, tired of his bargain, traded back and threw in a horse. This incident is not in the Bergen tradition. Its pioneers were mainly New Englanders and Pious, circumspect folk.

In stage coach days the principal settlement was on the hilly ground that to this day is called High Bergen. It also was known as Cork and Wardville. An early settler was Dr. Levi Ward, who later moved ro Rochester and founded a family distinguished in the scientific field. The coming of the railroad shifted the business center to the present village site on lower ground.

Bergen is on the Main Line and some 25 years ago nearly all the Central trains stopped there. Some 60 to 70 persons commuted daily to Rochester. Now all the passenger trains but one each ways flash through the village with a roar and a clatter, the shining Empire State, the lordly Twentieth Century and the humbler ones.

Today many residents work in Rochester, in Le Roy and Batavia, but they do their commuting by bus and automobile. The village has a canning factory, a flour mill and two produce warehouses. It is a farming region and agriculture dominates its economy.

Bergen is a homey, unpretentious sort of village. It is "a good town to live in."

There are few ancient landmarks in the business section—for a good reason. Bergen through the years has been dogged by a series of devastating fires. There was a serious fire in 1866. In March, 1880, flames left five acres, almost the entire business district, in ruins. Undaunted, the village rebuilt.

Then on New Year's Day, 1906, another blaze swept most of the same section. A call for help was sent to Batavia and the fire department of that city came by special train, the fire fighters in a coach, their apparatus on a flat car. The run was made in 11 minutes. After the fire was under control, and the 60 Batavia firemen were in their coach, ready to return home, it was struck by a fast freight at the Bergen station. The coach was rolled over on its side by the impact. Nine firemen were injured. It was almost miraculous that none was killed.

One building, that was once an inn, survived the several fires. The century-old one-time Hartford House now houses the village offices.

Bergen and its environs have produced some notable men. One was Galusha B. Anderson, born in North Bergen in 1832. He became president of the University of Chicago and of Denison College. He was the author of a book, "When Neighbors Were Neighbors," an account of life in his boyhood home.

Another was Frank J. Tone, who was born in Bergen in 1868 of pioneer stock. An inventor and metallurgist, he headed the great Carborundum industry at Niagara Falls. He was the father of Franchot Tone, the actor.

There are a lot of Bergens in the township—West Bergen, South Bergen, North Bergen. Once they were trading centers. In this age of automobiles and paved roads, they have all but vanished from the scene.

* * * *

About two miles west of the village of Bergen stretches a great swamp, five miles long and a half mile to a mile wide. The Bergen Swamp is far famed as a paradise for naturalists.

There bloom rare wild flowers, like the white Lady Slipper of the orchid family, whose pouch-shaped lip resembles a slipper. The Bergen Swamp Preservation Society has erected two signs near one entrance to the swamp. One says "Beware the Swamp Rattlers." The other warns that "the White Lady Slipper is protected by state law and that it is a criminal offense to pick, uproot or carry one away.

George Thompson, the village clerk, who has hunted in the swamp since boyhood, says the rattlers are few and that they are small ones.

The Bergen Swamp is privately owned, by various farmers. Its foundation is white marl, which has never been marketed, Cedar trees around its edges are cut up into fence posts and poles, usually when the ground is frozen.

Ever since 1917, Prof. W. C. Muenscher of the botany department of Cornell University has spent two or three days a month, from April to October, in the swamp. He has catalogued some 800 species of plant and animal life noted there. I quote from his report:

This swamp is a relatively primitive area in the midst of a highly developed agricultural region. Wheat, oats, rye, maize and tomatoes grow there, as well as many weeds and some exotic plants. There are trees of exotic species of cherries, pears and apples and seedlings of European mountain ash and white birch, Scotch pine and bushes of Japanese and European barberry and Tartarian honeysuckle.

"Ordinarily when several persons enter the swamp together, few large animals are observed. On one trip by myself, I noticed two deer, four red fox, several kinds of snakes, including one rattler, several grouse and turtles."

If you're thinking of exploring the Bergen Swamp—and lots of nature lovers do—"Beware the rattlers." "Don't pick the Lady Slippers" and, above all, wear hip boots.

The Big Springs

The Big Springs

THE old trail through the forest was only a yard wide. But the feet of generations of Indians, marching single file, had worn it deep.

In the days of Iroquois glory, that narrow path was their great highway, the Main Street of the Long House, for it linked the Hudson River with Lake Erie. Sometimes it was a war path.

Along that trail lay many a favorite camping ground. One was at the place where a dozen springs gushed our of the earth to foram a crystal lake and to feed a cold, swift stream in which trout darted. The Senecas called the place Gan-e-o-di-di-ya, which meant "handsome lake" and they had a village there. It was known far and wide as the Big Springs—until the Scotchmen came and called the village they founded Caledonia, which is the ancient name of their homeland.

Now "the handsome lake" is gone but the springs still feed the cold, swift brook in which still leap the trout. And today one of the white man's busiest highways, Route 5, the road across the state, follows the old Indian trail.

* * * *

No wonder there are so many historical markers and boulders around Caledonia and Mumford. The region of the Big Springs is historic ground.

No wonder there are so many historical markers and boulders around Caledonia and Mumford. The region of the Big Springs is historic ground.

It was a noted stopping place in the heyday of the Senecas. For there, as now, the trails converged. Around the Indian village were oak openings where the shaggy ponies browsed and there were wild plum trees and grape vines in abundance. And always the streams teeming with fish.

At the Big Springs were the trail houses for the war parties and the hunters. There stood the council elm where burned the fires of the Turtle Tribe. There was the stake where the captives were tortured. There the Red Men staged their foot races, their war dances, their feats of strength.

Then the white men came down the narrow trail. Probably the first was the Frenchman, Etienne Brule, scouting the Genesee Country for Champlain in 1615. Other Frenchmen passed that way, missionaries, traders, explorers, soldiers, and after the star of New France waned, the English troops and their savage allies in the colonial wars.

After Sullivan's raid broke the power of the Seneca empire during the Revolution, the Indian village was abandoned but the Big Springs continued to be a popular stopping place for white pioneers and roving Indians.

The site of the council elm today is marked by a boulder erected to the memory of the Seneca chiefs: Handsome Lake, the Peace Prophet who preached temperance to his people; his half brother, Cornplanter, Red Jacket and "the other Keepers of the Western Door." The memorial was put there by Gan-e-o-di-ya Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

Last year a gale toppled the old elm. Now it lies around the boulder like a fallen giant, its torso sawed into many pieces.

* * * *

There was no permanent white settlement at the Big Springs until 1795 when two Englishmen built a log tavern. They were unsavory characters and did not last long.

In 1749 came the real pioneers—of a different breed. The year before a band of Scots, tired of the tyranny of English landowners and of being pressed into English military service, left their Highland land hones in Perthshire and came to Broadalbin and Johnstown in Eastern New York.

At that time, a fellow Scot, Charles Williamson, was land agent for the British Pulteney interests with a vast wilderness on his hands. He had hoped to sell his lands to aristocrats for large estates, rather than to small settlers. But no landed gentry wanted the wild lands of the Big Springs region. Williamson heard of the Scotch emigrants at Johnstown and went to them with an offer of land on liberal terms. He assured them provisions until they were self supporting and also promised them the site of a church and 200 acres for religious and educational purposes. Charles Williamson knew his Scotch Presbyterians.

The canny Calvanists sent five of their number to look over the site before closing the deal. The five amen, each a "Mac," made the more than 200-mile journey on foot. They liked the lay of the land, gently rolling and unlike their own craggy highlands. They met Williamson near Geneva and signed up for 3,000 acres of Pulteney lands, But before they approached the courtly land agent, they stopped by a stream and carefully shaved with their pocket knives.

By spring of 1799, they had begun clearing their, new acres. Most of them came to the Genesee Country with only their clothes on their backs. They even traded some of their clothing for the use of oxen to break the sod. No pioneers were poorer in the world's goods. None were richer in spirit, They were resolute, frugal and hard working. And they were staunch Presbyterians who obeyed the laws of God and man.

* * * *

Within four years, the pioneers had formed a religious society. The next year they built a log schoolhouse on the banks of the Oatka. The Scots demanded the 200 acres Williamson had promised. But he was no longer the Pulteney land agent and it was three years before his successor, Robert Troup, fulfilled the pledge.

Meanwhile a group of Scots from Inverness had settled on a Holland Land Company tract south of the Pulteney lands. The men of Perthshire and the men of Inverness joined in building the new log kirk. But they were of different clans, settled on different lands, and soon a dispute arose. It lasted 18 years.

The Perthshire faction put a notice on the church forbidding entrance to all who did not live on the Pulteney lands. One of their number took from the wall of the house of Peter Campbell of the Inverness clan the key to the church. They kept it locked and guarded against their rivals, who for 17 years held their services in a private home. The discord was aired in the courts before the two societies reached an agreement on division of the land. But each maintained its own church.

That old feud was only a frontier incident and is all but forgotten. The real accomplishments of the pioneers are remembered. Where the Caledonia-Rochester Road joins the Oatka Trail, in July of 1926, there was a gathering of the clans and with skirl of bagpipes and singing by voices rich with the burr of Scotland, a boulder was dedicated to "The Scottish pioneers who built here in 1803 the first schoolhouse west of the Genesee and formed here in 1805 the Caledonia Presbyterian Kirk, oldest living church west of the river."

* * * *

The land was sowed to wheat and the Scottish colony prospered. The end of the first decade found at Caledonia a saw mill, a grist mill, a store, nine taverns, and it was a stage coach stop on the Albany-Buffalo route that followed the old Indian trail.

In 1802 a town called Southhampton was cut off the vast mother township of Northhampton. Within four years the Scotch had changed the name to Caledonia.

During the War of 1812 the old war path of the Senecas became a military highway again. Troops, bound for the Niagara frontier, detachments guarding British prisoners, marched through. One day a caravan of 100 great wagons, bearing 500 sailors on their way to join Perry's fleet on Lake Erie, stopped at the Big Springs. The sailors spied Robert McKay's potato patch and began to dig. The irate Scot ordered them off his land. The tars only laughed at him. McKay and some fellow Caledonians armed themselves and prepared to drive off the intruders. A battle was averted when naval officers, summoned from a tap room, ordered the men back to their wagons. Which incident shows the spirit of the pioneers—when their property was threatened.

Caledonia once was the terminus of a remarkable 6-mile pioneer railroad. In 1838 Wheatland farmers raised $40,000 and built the Scottsville & Le Roy Railroad. It was intended to reach Batavia but it stopped at Caledonia. Its rails were of oak, its ties of cedar. Strips of iron protected the rails at crossings. The rolling stock was four open trams and they were drawn by horses. Mostly the railroad hauled wheat and plaster. It lasted only 2 years, expiring after the advent of the Genesee Valley Canal. In 1938 a celebration marked the centennial of the pioneer railroad and early days were re-enacted with pageantry and oratory.

* * * *

From the beginning the Spring Brook that rose at the Big Springs and emptied into the Oatka Creek, teemed with fish. John McKay, a pioneer who ran a grist mill along the stream and who owned the present site of Mumford, told of catching with his bare hands three-pound trout that lay under the roots of cedar trees.

Probably more trout have been taken from that one and a half miles of rippling water than from any stream of its length in America. Piscatorial history has been made there and generations of am.lers have evaded its waters—and those of the Oatka.

In 1864, a bearded Rochesterian who devoted his adult life to the study of fish habits and who became famous as "the father of fish culture," started a commercial hatchery along Spring Brook. His name was Seth Green. There he made the pioneer experiments which resulted in the artificial propagation of fish. In 1875 the state took over Green's hatchery. Green became a state fish commissioner and continued his work, often studying the finny tribes in an old wooden building with darkened windows that stood over Spring Brook.

On the Caledonia Fish Hatchery's 27 acres are six buildings today for the selective breeding of various breeds of fish, mainly trout. There millions of fingerlings are produced annually for stocking the streams and lakes of the state. The temperature of Spring Brook varies less than 10 degrees the year around.

A boulder on the grounds honors the memory of Seth Green and his picture hangs above one of the breeding troughs.

An associate of Green in the field of fish culture was James Annin, who in 1872 started a private hatchery west of the state property. His son, Harry, still carries on the business under the name of Caledonia Trout Ponds. In that sylvan setting at one time a group of Rochester anglers, among them P. V. Crittenden and Willis Mitchell, the publisher, maintained a clubhouse.

James Annin, who died in 1930, has been called the dean of commercial fish propagators. Fingerlings from his hatcheries have peopled waters all over the Northeast. He introduced small mouth bass into England and stocked the streams of Lady Amherst's estate at the turn of the century. He led in the move to stock state streams with brown trout. Some sportsmen fought the invasion of that breed.

When Theodore Roosevelt was governor of New York, he was Annin's luncheon guest. TR asked Annin to serve him a brook trout. Annin slyly saw that his distinguished guest had a 2-pound brown trout. After Roosevelt had smacked his lips over "the bully American brook trout, the real thing," Annin confessed the artifice. TR was so impressed he shortly ordered the state steams thrown open to brown trout.

* * * *

Caledonia is not "county-line conscious." The Livingston County village is right at the borders of Monroe and Genesee. Its fair, which began in 1913, for years was the Tri-County Fair. One of the youngest fairs in the state, it is also one of the hardiest. During its 34 years it has skipped only one season and that was the war year of 1943 when gasoline rationing was toughest. The Caledonia Fair is a genuine old time country fair, one of the few left in these parts. Its half-mile track has known the thrills of the midget auto races and the roar of racing motorcycles, as well as the flying hooves of the trotters.

The Big Springs country, settled by Scots, has been peopled by many stocks. The Irish came to the region when the Genesee Valley Canal was dug. There is quite a Negro colony. Its presence is not traceable to activities of the Underground Railroad. One explanation is that long ago the thrifty Scotch farmers imported Negro labor from the South and that many of the emigrants stayed.

Many newcomers have come to dwell in Caledonia, with the old families whose Scotch forebears cleared the land. Many residents work in Rochester industries. Some are professional men in the city. Yet this village can never be dismissed as a suburb. Caledonia has its own robust individuality.

And it has its own industries, foremost of which is a factory that makes coils for radios, airplanes and other uses and which occupies the former high school property. There also is a tack factory, in addition to a large Grange League Federation warehouse.

Five railroads run through the town, among them the remains of "The Peanut Line" of the New York Central and the nine-mile Genesee and Wyoming, "The Gee-Whiz" line, which hauls salt from the big Retsof mines.

* * * *

There are many landmarks in this old town on the Great Trail where the past and the present are so intermingled.

One is the neat stone building that houses the public library. It was built in 1826 and was the first post office, bank and apothecary shop. A few doors away is the charming stone residence of F. F. Keith, village editor and student of local history. It was built in 1827 and served in early days as a tavern.

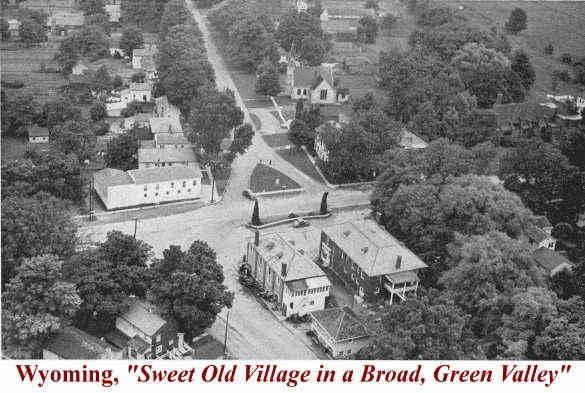

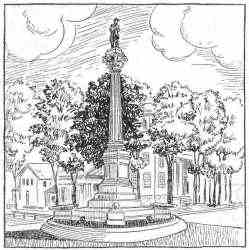

At the crossroads where the tall war memorial monument stands guard is the imposing, three-story stone structure that now is the Masonic Temple and post office. It was built in the early 1830's as an inn. Its old balcony, overhanging the one-time driveway and supported by stone posts from which still hang hitching rings for horses—all these tell of the days when the stage coaches lumbered up to its doors.

Two serious fires, a few years apart, the last one around the turn of the century, struck two different parts of the business section. The debris of the last blaze was thrown into the "handsome lake" of the Senecas, which had been steadily dwindling through the years. Then it was covered with topsoil and converted into an athletic field. The former high school building at the historic spot now is appropriately the home of the Big Springs Historical Society.

Old residents recall when there was an island in the center of the lake and rowboats plied its waters. The New York Central tracks were carried over the waters by a trestle. One reason the lake was doomed was because moss forming there in dry times sullied the waters of the state fish hatchery.

Now there are only the historical markers to tell of the Senecas' tarrying place beside the crystal waters. But ghosts must walk the Big Springs at night—the ghosts of the chiefs, Handsome Lake and Cornplanter, up from Canawaugus Town; of the warriors, the hunters, the fishermen of the tribes; of the French priests and soldiers; of the Red Coats of Sir William Johnson's command; of the many wayfarers who knew the old camp ground beside the Great Trail.

In sharp contrast to Caledonia's old stone residences, many white houses, stately churches and other landmarks, is a very modern real estate development on the edge of the village, off the Avon Road—a cluster of prefabricated houses.

Farther down that road is a boulder, marking the last resting place of a soldier of the War of 1812 and on it is a verse, famous in its day, written by a Caledonian. "Poet John" McNaughton, they called him to distinguish him from other John McNaughtons. It reads:

- "My brave lad, he sleeps

- In his faded coat of blue.

- In his lonely grave unknown

- Lies the heart that beat so true."

"Poet John" also composed music and after the Civil War was leader of the Caledonia Military Band, known far and wide in its time.

Caledonia, one of the few towns in this region founded by Scots, retains many of the rock ribbed characteristics of its fathers. And it has a serenity and a poise, born of its long years beside the Great Trail, watching the parade of history file past the Big Springs.

* * * *

The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad has a station labeled "Caledonia-Mumford." The grouping is entirely logical. Although the two villages, only a mile apart, are in different counties, they have a common history and tradition.

Mumford, just over the line in Monroe County and in the aptly and euphoniously named Town of Wheatland, was settled by the same band of hardy Scots who fathered Caledonia. It was first called McKenzie's Corners. Then it was variously Slab City, in lumbering days; and Mumfordville, after a leading citizen. The "ville" was dropped years ago.

Many are the echoes of the past in this quiet village on the old stage coach road between Rochester and Caledonia. The slate-colored brick Community Building at the four corners was the Exchange Hotel in stage coach times. There are hitching rings on its front today. Just around the corner is the frame house, painted brown, that was the Donnelly House, an inn in other days. Once the town pump and watering trough, surrounded by a white railing, stood in the center of the four corners. On a side street is a genuine "Little Red Schoolhouse" with a white belfry crowning its brick walls.

And there is "the church of petrified wood." The Gothic Presbyterian edifice was built in 1863 of undressed blocks of marl taken from a nearby swamp. The stone in some places present a fibrous appearance, hence the "petrified wood" illusion. At first it was white but the years and the elements have turned it into a mottled brown and white, with the white stones presenting a frosty appearance.

There are homes around Mumford in which generations of the same family have lived for more than a century. An example is the cobblestone house that Donald Mann, who came with the first Inverness Scots, built southeast of Mumford and which until five years ago remained in the hands of his descendants. Among those descendants were two bishops of the Episcopal Church.

Queen of the Oatka

Queen of the Oatka

THE woods were flaunting their richest October plumage that afternoon in 1798 when a horseman rode down the old Indian trail that led from the Hudson to the Niagara.

It had been but a narrow path in the time of the Senecas. Now the white pioneers had widened it so that their wagons could pass. But still it was a bumpy road through an almost unbroken forest. In 1798 the Genesee Country was wild and young and settlers were few.

The horseman in fashionable cloak and three-cornered hat was no frontiersman. He was a French emigre of noble birth, the Count de Colbert Maulevrier and he was touring the hinterland and jotting down his impressions in his journal.

He came to a clearing with a huddle of five or six log houses. One was the tavern of John Ganson and the place was called Ganson's Settlement. It was the beginnings of the village of Le Roy.

On opening the tavern door, the count was surprised to find "nine ladies in their best attire, gravely seated opposite each other, with all the preparations for a grand tea."

"A little afterward," he wrote in his journal, "nine gentlemen who had been helping John Ganson harvest his corn, appeared... After tea, supper was served, first to the ladies, then to the men... All joined in a dance until 11 o'clock..."

The titled traveler had hardly expected to find such observance of the social niceties in a tiny backwoods settlement.

So you see Le Roy had "tone"—even in its cradle.

* * * *

Travel today by auto or bus the road that spans the state, that has been in turn Indian war path, pioneers' wagon trail, stage coach turnpike and now is busy Route 5 and you will find on the site of Ganson's Settlement a neat, attractive and distinctive village of some 4,500 souls.

Le Roy's setting is picturesque. The Oatka (in Le Roy it is the Oatka RIVER, never creek) rolls through the heart of the village. Oatka's waterfall, once far mightier, gave the town commercial life. Few high schools can boast a campus like Le Roy's, a broad green expanse beside a stream. For half a century it was the campus of a college. Ingham University for young women closed its doors 55 years ago but the cultural quality it gave the village has not departed.

Le Roy's setting is picturesque. The Oatka (in Le Roy it is the Oatka RIVER, never creek) rolls through the heart of the village. Oatka's waterfall, once far mightier, gave the town commercial life. Few high schools can boast a campus like Le Roy's, a broad green expanse beside a stream. For half a century it was the campus of a college. Ingham University for young women closed its doors 55 years ago but the cultural quality it gave the village has not departed.

There's a distinguished air about this Genesee County community. The many fine old post colonial homes and other buildings—and some of them were inns in stage coach days—the stately churches, all tell the traveler that here is no mushroom town.

Here is an industrial center—with none of the usual gritty earmarks. Products known the world over have been and are being made in Le Roy. They made some princely fortunes, too. Set well back from the broad main street and behind thick curtains of greenery are the mansions that Jello and cough syrup and other Le Roy products built.

Despite its affluence, its sophisticated background, Le Roy is as friendly and democratic a village as you will find anywhere. To sum up, here is a village with a lot of class.

* * * *

Before the Senecas came, prehistoric tribes had a stronghold three miles north of the village at the confluence of the Oatka and Fordham Brook. It is called Fort Hill and many evidences of pre-Iroduois occupation have been unearthed there. Its commanding situation on an eminence, surrounded by an entrenchment, indicates it was built for defense.

At Buttermilk Falls, in the present village, once was a Seneca camping ground. There the first mills were built. Now the 90-foot cataract north of Le Roy that once was Oatka Falls has taken over the old name, Buttermilk Falls. This waterfall, really spectacular save in the dry season, is off the beaten path and seems "born to splash unseen."

The Oatka, which means in the Indian tongue "through the opening," was called Allen's Creek by the pioneers because where it joins the Genesee near Scottsville lived Ebenezer (Indian) Allen, one of the first white men in the Genesee Country.

As early as 1793 stout-hearted Charles Wilbur reared a lonely log cabin on the site of Le Roy. Four years later he sold it to John Ganson, who as a soldier with Sullivan's expedition, had divined the rich promise of the countryside. Ganson's tavern became a celebrated stopping place, particularly after the Holland Company began selling land to settlers at Batavia and the old trail swarmed with carts and wagons.

In 1793 Herman Le Roy, a New York capitalist with a proud old French name, and his associates, William Bayard and John McEvers, bought 85,000 acres from Robert Morris. It was called the Triangle Tract—for obvious reasons—and it included the site of Le Roy, which became "the capital" of this purchase. In 1801 a crude log land office was built beside the Buttermilk Falls. In 1813 Land Agent Egbert Benson built a larger, finer one of brick. When Jacob Le Roy, son of Herman, became the land agent in 1822, he enlarged the land office into the spacious mansion that still stands on East Main Street and which is the home of the Le Roy Historical Society.

The Le Roys were patricians and made their imprint on the frontier community. Jacob built mills on the Oatka. He helped build the first St. Mark's Episcopal Church at St. Mark's and Church Streets. The old Episcopal graveyard is still there with the dates on the headstones going back to 1818.

Charlotte Le Roy, wife of Jacob, once presented a bell to St. Mark's with the request that it be rung at the end of the service as well as before its start so that her coachman would not arrive too early and have to wait. Which seems most considerate, although the fact remains that the church was right around the corner from the Le Roy mansion—a short walk. But the Le Roys were the kind of folks who rode in carriages.

Le Roy had a sprinkling of Dutch settlers, probably because of the influence of its New York City land grandees but its fundamental underlay is New England, plus some of the same doughty Scots who settled the Caledonia-Mumford region. Today it has a sizeable Italian-American population.

In 1812 amid the second war with Britain a new town was carved from Caledonia, then in Genesee Country. It was first called Bellona after the goddess of battles but in 1813 was renamed Le Roy in honor of the land owner-founder.

The village was incorporated in 1834, the same year Rochester became a city. The first official act of the village fathers was to acquire a hand-drawn fire engine, operated by two hand cranks.

Le Roy was a hotbed of the Anti-Masonic furor of the 1820's that followed the disappearance of William Morgan, the bricklayer, who had threatened to expose the secrets of the Masonic order. Morgan had worked in Le Roy and had friends there. In May, 1825 he was made a Royal Arch Mason in Le Roy. Some historians maintain it was the only legitimate Masonic degree he ever held.

At that time Le Roy lodge planned a splendid temple, three stories high and circular in shape. The story goes that Morgan's disappointment over his failure to obtain the contract to build this temple whetted his grievances against the fraternity. The Morgan excitement prevented the Masons from ever using the Round House, as their temple was called. After serving as a church and a school, it was demolished in the 1850's.

Le Roy in 1827 was the scene of the first state convention, of the Anti-Masonic Party, the creation of Thurlow Weed and other manipulators of public passion to serve their own political ends. Twenty years elapsed before Free Masonry was revived openly in Le Roy.

* * * *

The village became a college town in 1837 when the Misses Marlette and Emily Ingham opened the Le Roy Female Seminary after operating a school for two years in Attica. The school acquired the Bayard estate along the Oatka and imposing buildings rose on the campus. In 1852 the name was changed to Ingham Collegiate Institute and in 1857 it was chartered as Ingham University. For 41 years, until 1883, it operated under the wing of the Presbyterian Synod of Genesee.

Ingham had several chancellors. The only one to gain the national limelight was the Rev. Dr. Samuel D. Burchard, who served from 1866 to 1872. His fame came from three alliterative words. It was this Presbyterian divine who in 1884 as the spokesman for a group of New York City clergymen calling upon James G. Blaine, the Republican candidate for President, referred to the Democrats as "the party of Rum, Romanism and Rebellion." On the eve of the election Blaine let the remark pass unrebuked and as a result he lost the Catholic vote of New York—and the presidency to Grover Cleveland.

Changing times forced the closing of the University in 1892. The last of the sister founders, Mrs. Emily Staunton, had died in 1889. In its time Ingham drew students from many states. Many of them attained distinction, particularly in the fields of art and music. The school raised the cultural level of Le Roy. And today scattered over the land are gray-haired women who look back fondly on their college days beside the still waters of the Oatka.

* * * *

In 1845 Peter Cooper, builder of the first American locomotive, filed specifications in the Patent Office for a product requiring only the addition of hot water for the preparation of jelly for table use. It never was marketed and the idea forgotten. In 1900 it was revived in a humble home in Le Roy where a man named Pearl B. Wait began making the dessert called Jello. A shrewd Le Roy manufacturer, Orator F. Woodward, bought the formula—and he paid no king's ransom for it.

Jello made Orator Woodward a multi-millionaire. It made other fortunes, too, and it has provided Le Roy with a thriving industry for nearly 50 years. In the early days, Woodward sent his sales representatives—and many were Le Roy men—all over the Country pushing the product. After O. F. Woodward's death in 1906 at the age of 50, his family carried on the management of the industry. Now it is a part of the General Foods Colossus.

Horatio Alger could have fashioned a book out of Orator Woodward's career. Born in nearby North Bergen, he came to Le Roy when 4 years old and was earning his own way at the age of 12. He had an ingenious turn of mind and he was a born merchandiser. He began his industrial career as the maker of composition balls used as targets by marksmen before the day of clay pigeons. Then he evolved a patent nest egg which he made in a small building in Mill Street. In 1883 he went into the patent medicine business and his wagons rattled over the country roads. His son, Donald, now carries on the proprietary medicine business under the Kemp and Lane label. In 1896 O. F. Woodward began marketing a cereal coffee called Graino. Then came Jello and great riches.

Le Roy is the birthplace of the stringless bean as well as Jello. In the 1870's Nicholas B. Keeney and his son, Calvin, began the cross fertilization of 40 or more bean plants and over several seasons worked out all but the stringless pods. This brought to the market for the first time the stringless bean.

Once Le Roy table salt was famous and there were a dozen salt welts in the town. The first one was duigin 1879 and by 1897 Le Roy wells were producing 1,000 barrels a day. Today the towering stack of the abandoned salt block west of the village is the only reminder of a once important industry.

There are three huge stone buildings along the Baltimore & Ohio tracks that now serve various purposes. Once they housed the shops where Senator A. S. Upham built cars for the New York Central Railroad while he served the Vanderbilt interests in the Legislature. Later on they became malthouses.

For years Le Roy has sent out a stream of proprietary medicines ranging from cough syrup to foot powder. In 1871 Schuyler C. Wells Sr., who had operated a village drug store, started making the Shiloh line of remedies. His son, Schuyler C. (Carl), one of Le Roy's most influential citizens, today heads the very substantial business his father founded. The Olmsted interests made Allen's Foot Ease in Le Roy for years.

Popular belief to the contrary, jello right now is not Le Roy's major industry, That distinction goes to the Lapp Insulator Company whose expanding plant on the edge of the village began some 25 years ago when John and Grover Lapp came to town from Victor. Lapp employees are drawn from all over the countryside.

Le Roy also makes plows, steel boxes, cartons. It has produce warehouses and a crushed stone industry. Still it does not seem like an industrial center.

* * * *

Tracks of three of the railroads entering Le Roy, the Baltimore & Ohio, the Erie and the "Peanut" branch of the New York Central,

cross at a common point and thereby hangs a tale.

In 1878 when the Rochester & State Line Railway, which became the Buffalo, Rochester & Pittsburgh and is now part of the B&O system, was being built, there was a hitch in the negotiations over the new road's crossing the Erie and Central tracks in Le Roy.

The contractor, scornful of red tape, was determined to push a construction train across the other lines and hastily built a temporary track for that purpose. Erie authorities got wind of what was going on and an Erie locomotive, its cab full of men ordered to stop the crossing, came roaring down from Caledonia. It was too late. The State Line train had just cleared the crossing. Then the whistle of its locomotive, The City of Rochester, sent the jubilant echoes flying. All that night an Erie engine ran up and down the track to prevent return of the State Line train.

This nugget of lore came from the scrap book of Fred B. Robinson, for many years on the editorial staff of The Democrat and Chronicle, who lived in Le Roy in his youth.

* * * *

Le Roy's magnates have been generous givers to their village and active in its affairs.

The splendid library building on the high school campus was the gift in 1939 of the sons and daughters of Orator F. and Cora Talmadge Woodward as a memorial to their parents. A recent Woodward gift was that of the mansion and grounds on the hill at the eastern edge of the village to the University of Rochester for use as a research clinic in the war on cerebral palsy and polio.

Ernest L. Woodward, son of O. F., can be called Le Roy's first citizen without fear of contradiction. In 1937 he gave the land along the Oatka, at what old timers call "The Dock," as the site for a new postoffice. When it was learned Uncle Sam proposed to erect it flat, squat structure, dwarfed by its neighbors and clashing with them architecturally, it was Ernest Woodward who directed an emphatic protest to Washington and it was he who spent some $20,000 of his own money so that Le Roy's Postoffice would be a tasteful building, with gables, parapet walls and built of native stone and not of brick—not a flat-roofed monstrosity.

Another native Le Royan, Allen S. Olmsted, whose family fortune is based on Allen's Foot Ease, made possible the preservation of the former Jacob Le Roy mansion as an historical shrine. The stately two-story house came into his possession along with the wooden former Academic Institute and the old stone Le Roy High School in its rear. The Olmsted interests for some years made their foot preparation in the school buildings. After 1911 the Le Roy home was the residence of the high school principal under the terms of Olmsted's gift to the school district. In 1942 Le Roy House and the old school buildings were given to the Le Roy Historical Society.

Le Roy House is an antiquarian's "Never Never Land." From the walls of the high ceilinged rooms with their white woodwork and their spacious fireplaces, the pictured faces of the Le Roy clan look down. The mansion is full of treasured mementoes of the past—the concert grand piano that was the pride of Inghaam University; period candlesticks, silver, costumes, pottery; relics of the pioneer time, spinning wheels, churns, apple corers, military objects, old documents, books—not to mention the bell of the old Academy.

In the basement of the former high school is the carriage in which President McKinley rode to the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo the day in 1901 that he was shot down. It is the gift of Edward H. Butler, publisher of the Buffalo Evening News, whose father was born in Le Roy. In a room where once Foot Ease was made is an airplane that one of the Buffalo Olmsteds constructed some 30 years ago and that never left the ground.

When the Historical Society took over Le Roy House, an old-fashioned fireplace with bake ovens was found behind a brick wall in the basement. Recently when regional historians met there, they were served hot bread baked in those ovens.

Le Roy House is a museum with a home-like, rather than an institutional, atmosphere. It is used as a meeting place for the DAR and other groups. The village and region have cooperated splendidly in the project.

The president of the Historical Society is energetic Roy P. McPherson, about the only large-scale orchardist in the town and the veteran secretary of the State Horticultural Society. The descendant of pioneers, McPherson lives in a 135-year-old house on the Oatka Trail. The curator of Le Roy House is Albert F. McVean, a veritable fountain of Le Roy history and lore.

Le Roy House has a roomy back porch. It was even larger in the days when the young ladies of Ingham University occupied the house. The poach was known as "The Galleries" then.

It was on that old porch that Daniel Webster courted his second wife, Caroline, daughter of Herman Le Roy. He was 47 and she was 32 when they married in 1829. One wonders what eloquence "The Godlike Daniel," the greatest orator of his time, poured into the ear of the fair and buxom daughter of the House of Le Roy on that porch 118 years ago.

There are so many landmarks, so many echoes of the past in Le Roy—the Eagle Hotel, built in 1825 and famous in stage coach days; the Wiss House, now a hotel but built around 1815 as a store by Samuel De Veaux; who later made millions and founded De Veaux school at Niagara Falls; the exquisite residence of Harold B. Ward, at West Main and Craigie Streets, painted white and a tribute to the good taste of the pioneers, with its carved woodwork and pantry shelves of cherry wood (it was built as an inn in 1812 and in an upper room long ago the Masons met in secret); the former Lent Tavern across the street, erected in 1813, and now a charming private residence; the turreted rococo West Main Street mansion that once was the summer home of Edward H. Butler Sr., founder of the Buffalo News, with its huge stables that housed the Butler horses, tallyho and carriages. Now it is the Knights of Columbus clubhouse.

Le Roy is mighty proud of its pure water supply which comes down from two artificial lakes some miles from the village. One is called Lake LaGrange. The other, the first one created, is Lake Perkins. It is named in honor of E. M. Perkins, publisher of the News-Gazette (founded 1826), who led the movement for a better water system. Perkins probably is the only one in his profession to have a lake named after him.

* * * *

The late Jesse Rainsford Sprague attained considerable renown as a writer for magazines. His specialty was writing about small businesses that were successful in unusual ways. Several years ago there appeared in Scribner's a Sprague article on an entirely different theme.

Titled "Jug City," it was an entertaining story of Sprague's birthplace just south of Le Roy.

"Jug City came by its name honestly," Sprague wrote. "Just after the War of 1812 a man named Shelby started a whisky distillery on the creek and to promote the sale of his merchandise, set up a liberty pole at the four corners with a little brown jug at the top."

Jug City must have been a lively place when Jesse Sprague was a boy there. He told of the cooper shop, the pump factory, the schoolhouse, the church and of some fascinating Jug City characters. One was the woman called "The Widow" who was shunned by the "best people" because of nights strange horses and buggies were sometimes tied at her gate.

Roy McPherson drove me out to Jug City. On the way he pointed out the Victorian farmhouse where Jesse Rainsford Sprague was born.

Jug City is no more. At the crossroads there are only a couple of farmhouses, the creek and the old cemetery on the hillside where once it community flourished.

"The Great Meeting Place"

"The Great Meeting Place"

"THE Great Meeting Place" the Senecas called their town at the bend of the Tonawanda where the great trails converged.

Today it is the meeting place of the tides of motor traffic that flow across the state. On the busy mile of Route 5 that is Batavia's broad Main Street the traffic stream is slowed to a crawl.

On summer nights the old Fair Grounds is the "great meeting place" of the devotees of harness racing and the Daily Double.

But Batavia is more than that. Above the ceaseless beat of the traffic tide, above the roar of the crowd at Batavia Downs, if you listen, you can hear the distant throb of the drums. They are the drums of history.

For Batavia stands on historic ground. It was the stage on which was played much of the stirring drama of the frontier. It was a capital of that frontier, the seat of a great land company, when Rochester was a dismal swamp and Buffalo was a huddle of Indian huts.

Since 1802 Batavia has been the shire town of Genesee County which once embraced virtually all of York State west of the Genesee River.

Batavia was a haven for refugees in the War of 1812, a hotbed

of the Anti-Masonic turmoil of the 1820's and of the "Rent War" of the 1830's.

This grand old town is saturated in history. The many landmarks that go back over 120 years, the faded splendor of the mansions in East Main Street where once Very Important People lived; the dignified old stone Courthouse with its cupola and the War Memorial that dominate the historic crossroads at the bend of the main road—all these tell of Batavia's long proud history.

Yet this city with a polyglot population of some 20,000 does not live in the past. It is a brisk town, a part of the living present, and essentially an industrial city. The smoke of its factories is the incense at its altar. Before the railroads and the industries came, Batavia was the trading center of an extensive farming region. It still is.

Batavia is a lively, blithe dowager, mellow and urbane with wise old eyes that have seen the whole American procession file past her doors.

* * * *

In the long ago the Seneca council fires blazed at the camp ground at the sweeping bend of the Tonawanda Creek, which means "swift water," where the Great Central Trail from the Hudson to the Niagara met the path from Lake Ontario to the Susquehanna.

Then came the Revolution and the downfall of the Indian Nation. A vast new land was opened to settlement. In 1792 and '93 representatives of the Holland Land Company, made up of capitalists of old Amsterdam, bought from the tottering American financier, Robert Morris, more than three million wilderness acres west of the Genesee. It was not until 1797 that the Indian title was extinguished by the Treaty of Big Tree.

The next year the father of Batavia, the ruling spirit of the Holland Purchase, came upon the stage. He was Joseph Ellicott, a 6-foot Marylander, who had helped lay out the City of Washington and who had been engaged to survey the Holland Purchase. Eventually he became the land agent.

He fixed the Transit Line to determine the eastern boundaries of the Purchase. With the aid of the Indians, lie hewed a road through the forest 100 feet wide. It is Batavia's Main Street today. IIe chose "The bend of the Tonawanda" as the site of the land office and in 1801 began the sale of lots from a two-story log structure opposite the present Land Office Museum in West Main Street.

The company had hoped to sell its lands in large estates. But young men of the type who would brave the wilds of the Genesee Country had little cash. Wise Joseph Ellicott waived the one-tenth down payment and cut the price to $2 an acre. At first sales were slow but soon the roads swarmed with the settlers' wagons.

At first the site of the land office was called simply "The Bend," then it was Tonnewanta. When Ellicott proposed to name the place after Paul Busti, the Italian-born general anent, that worthy declared, "Busti sounds atrocious," which it does. He suggested Ellicottstown but the surveyor demurred. After that Gaston-Alphonse exchange, the settlement was christened Batavia, the name of the then Dutch Republic.

Ellicott fathered other communities, Buffalo among them. But Batavia had a special place in his affections. He said: "I intend to do what I can for Batavia because the Almighty will look out for Buffalo."

In 1802 Genesee County was carved from the mother of all Western New York counties, Ontario, and the town of Batavia was created. Batavia was made the county seat and a $10,000 Courthouse was built, the first one west of the Genesee. As Ellicott Hall, that three-story cupolaed structure lingered on the scene until flames devoured it in 1918.

Ill health beset Joseph Ellicott and he resigned his post in 1821. Five years later he died—by his own Band—in Bellevue Hospital, New York. He sleeps in the old Batavia cemetery between the Erie and the Central tracks under a simple, stately monument. The mansion he built became in 1850 the home of Bryan Seminary for Young Ladies. It was razed in 1887 to make way for Dellinger Avenue.

* * * *

In 1808 the stage coaches began rolling down the trail from that other frontier capital, Canandaigua. The first tavern was opposite the present Land Office Museum and the second one, "The Snake Den," at Main and State, advertised "clean sheets slept in only a few times since new.

The development of the Purchase was retarded by the War of 1812 and Batavia became a behind the lines headquarters of the American Army of the frontier, with a log arsenal on the Alexander Road.

After the British routed the Americans and burned Black Rock and Buffalo in the waning days of the year 1813, the fleeing soldiers, with the sick and wounded in sleighs and on litters, and an almost unbroken procession of terrified civilians, men, women and children, some of them tramping through the snow, poured into Batavia. Some backwoods settlements were deserted.

Years afterwards there was a similar pitiful procession on the Blitz-torn roads of France.

Every building in Batavia was filled to overflowing. Ellicott's mansion housed the Army officers and the Land Office became a hospital. A relief fund was raised for the refugees.

When the British made no move to push eastward, the scare died down. In 1814 a massive stone arsenal was built at the Buffalo and Lewiston Roads. This "guardian of the frontier" was razed in 1872.

By 1825, the year the Eric Canal was completed, Batavia had

3,352 inhabitants, 1,000 more than Buffalo, but 1,700 less than Rochester, already a boom town, thanks to the magic waters of the Clinton Ditch. After that Batavia, midway between the two big cities, was hopelessly outdistanced in the population race.

* * * *

There lived in 1826, with his wife and two young children in a house on Batavia's Walnut Street, a 51-year-old bricklayer named William Morgan. He was glib of tongue and shifty of eye. After he had been denied admission to a chapter of Royal Arch Masons at Batavia, the embittered Morgan joined with a village editor, David C. Miller, in an announced plan to publish the secrets of Free Masonry. That spark touched off a flame that was to sweep the nation.