Grand Dame of "The Tier"

Grand Dame of "The Tier"OUR Stage Coach Tour follows an old trail along a winding river where great hills with leonine heads stand guard.

Crinoline and broadcloth ride with us. Our coach is the finest of the fleet, the "flagship" of the line. The horses have been groomed until their sides glisten as brightly as the freshly burnished harness trimmings. The driver has donned his best livery and he sounds the horn with a rich, full note. The pert post boy stiffens to attention. The four horses do not gallop nor do they loiter. They trot grandly along.

For we are pulling into Bath. And Bath is "The Grand Dame of the Southern Tier."

This Stage Coach Town is no ordinary stop on the highway of history. Visiting Bath is like turning a page in a rare old book.

There's almost the air of a capital city about this old town on the banks of the Conhocton although it has only some 5,000 population and is the seat of government merely of the County of Steuben. At that it has to share its court terms with neighbors Hornell and Corning.

Streets, broad and straight, and laid out according to an orderly plan, tell even the casual visitor that long ago some bold dreamer planned a city here. The stately square in the village's heart, flanked by the bluff-colored county buildings and by pillared mansions, tells of a distinguished past.

Pulteney Square was a cradle of the frontier. There Charles Williamson, land agent with two million wilderness acres to sell and to settle, dreamed his bright dream of commercial glory. There in 1793 his axmen who had cut the Williamson Road over the mountains from Pennsylvania to the Genesee, made the first clearing in the Conhocton Valley. There they built the land office that made Bath a capital of the frontier. There was printed the first newspaper in the Genesee Country. There the first theater in the backwoods presented the sophisticated comedies of Moliere. There, ion, was played much of the real life drama of a raw young land.

Bath is a dream that never came true. It never became the great city of the land agent's vision. It did grow into a handsome county seat town, an important trading center. The smoke of roaring factories has never stained its historic buildings. Bath had no Houghton family, like Corning, to found a mighty glass industry in its midst. It had no sprawling car shops, no railroad yards as in Hornell. But Bath has a distinction that no industrial town can achieve. It has its mellow traditions and a gracious way of life.

"The Grand Dame" is not austere. She is a very great old lady, to the manner born, and needs put on no airs. Her people are "Quality Folk" in the best meaning of the word.

* * * *

During the feverish days of land speculation in the wake of the Revolution, Bath was born in the busy brain of the greatest real estate salesman of his time. Scottish-born Charles Williamson, agent for the British Pulteney interests, was a former soldier of the Crown, an enterprising, daring nian with the superb optimism of the born promoter. And he had a charm that few men—or women—could resist.

He picked the basin of the Conhocton, a broad valley surrounded on three sides by high and mighty hills, as the center of his "empire." He saw in his minds eye the commerce of the frontier floating down the lesser rivers to the Susquehanna and the great port of Baltimore. He could not foresee the coming of the Erie Canal to cut a shorter outlet to the sea and make New York the commercial mistress of the western world.

He picked the basin of the Conhocton, a broad valley surrounded on three sides by high and mighty hills, as the center of his "empire." He saw in his minds eye the commerce of the frontier floating down the lesser rivers to the Susquehanna and the great port of Baltimore. He could not foresee the coming of the Erie Canal to cut a shorter outlet to the sea and make New York the commercial mistress of the western world.

At the junction of his land and water highways, Williamson envisioned a trading and manufacturing center which he would call Bath after the seat of his British principal, Sir William Pulteney.

The land agent did things with celerity and on a grand scale. As if by magic a settlement arose at Pulteney Square, the agent's house. the land office, a tavern and cabins to the number of 50. Then came grist and saw mills, the newspaper and the theater. When a new county was formed and named after the German Baron Steuben, a hero of the Revolution, Williamson saw to it that Bath, the pride of his heart, became the shire town.

He built the finest residence on the frontier, a frame mansion with wings and porches and elaborate gardens, beside a sparkling little lake which he called Salubra. The hospitality, choice viands, pine wines of Springfield Farms became famous. There the petulant Abigail, the Boston girl who had married the British captain when he was a prisoner of war, played hostess. Celebrated guests came, among them Louis Philippe, later to become king of France; the Duke de Liancourt, English travelers, American statesmen.

In 1795, as a promotion stunt to lure land buyers, Williamson laid out a race course at Bath and announced a fair, racing meet, barbecue and wrestling matches on a scale unheard of on any frontier. He sent couriers in all directions with handbills which proclaimed:

"There will be trusty and civil guides to meet and conduct gentlemen and their suites to the far famed city on the tipper reaches of the Susquehanna, in the land of crystal lakes and memorial parks, located in the garden home of the lately vanquished Iroquois."

Williamson was something of an advertising copy writer as well as a promoter.

In August caravans rolled into Bath from all directions. Plantation owners with their Negroes; gamesters, jockeys, hunters, backwoodsmen, Indians, society ladies, pioneer women with calloused hands, to the number of 2,000 gathered on the Pine Plains of Bath, awaiting the starting gun.

There were no pari-mutuel windows but large sums changed hands. Williamson's Southern mare, Virginia Nell, raced Sheriff Dunn's New Jersey Silk Stocking, and lost. The wives of the two owners wagered $100 and a pipe of wine on the result and dumped the gold coins into the apron of a third lady who was stakeholder.

There was a sprinkling of New Englanders among the Southerners, Scots, New Jersey and Pennsylvania pioneers, and Mohawk Valley Dutch who had settled in the vale of the Conhocton and they looked askance at the racing and the betting, the revelry in the tavern and the new theater. Jemima Wilkinson, the Universal Friend, ruler of a fanatical religious colony near Keuka Lake, regarded Bath as a den of the devil.

Williamson, reared among patricians, desired aristocratic settlers and leaned toward Southern gentry. It was through his promotions that the Rochesters, the Fitzhughs, the Carrolls and others came from Dixie to the Genesee Country. But in the end he had to sell most of his lands to impecunious followers of the Jeffersonian democracy.

By 1796 Bath had 800 people. From the boom town on the Conhocton arks, really huge rafts, carried timber and other products down the rivers to Baltimore—when the water was high enough.

Troubles beset the dashing land agent. Bath had the invasion jitters in 1794 when a British-Indian alliance seemed imminent. A stockade was built and the militia drilled in Pulteney Square. But "Mad Anthony" Wayne's victory in the West restored calm.

The "Genesee Fever" struck at the log houses and laid even the vigorous Williamson low. His daughter, Christian, died in 1797 at the age of 5 and her grave was the first dug in the settlement. She sleeps in the old Presbyterian cemetery in the heart of Bath, at Steuben and Howell Streets, a little bit of the long ago amid the modern hustle.

The captain was a wordly man who walked the primrose Pith and he and Abigail became estranged. Then the Virginia major, Henry Thornton, and his beautiful titian-haired wife came to live in the Williamson mansion.

Williamson's greatest cross was his financial worries. He fell into disfavor with his home office because he was spending too much British gold developing his "empire." And he was born a Scot!

In 1801 the less grandiose Robert Troup supplanted him as land agent and Williamson left his "garden home." He died of yellow fever in 1806 aboard a ship bound for the West Indies.

In fancy one today can look up the broad principal street of Bath toward the Pulteney Square, with its backdrop of green and towering bill, and see again a gallant figure on horseback, a tall, handsome man in a blue cloak, a tricorn hat and powdered wig. After "154 years, his "city in the land of crystal lakes" bears the imprint of the careful planning and the sanguine spirit of Charles Williamson.

* * * *

The Pulteney estate passed through many British hands and it was not until 1914 that its affairs were finally closed although most of the lands had been sold in the early time. The old land office was torn down a few years ago. It seems a shame that it was not preserved.

For these 23 years a kindly, sagacious gentleman of the old school, Reuben B. Oldfield, has presided over the county clerk's office on the square. About everybody in the county knows him. He is a terrific vote-getter. He also is an authority on local history and Indian lore and he is the author of eight books for children. His talk, always sparkling, is punctuated with infectious chuckles.

For my benefit, Oldfield opened a ponderous safe in his office on a June night and as fondly as a virtuoso would handle a Stradivarius, he drew out a sheaf of ancient documents. They were the papers of the Pulteney Estate, most of them sheepskin parchments and well preserved. They were writen in the finest copperplate. Some of them had scalloped edges. The torn pieces had been given as "receipts" to pioneers who could not read or write but who could match pieces of torn parchment.

On the papers stood names that here famous in young America. There was the deed of two million acres from Robert Morris to Charles Williamson. Another document conveyed a tract near the Genesee Falls to James Wadsworth. There was the 11-page will of Henrietta Laura, Countess of Bath, and daughter of Sir William Pulteney, 29 inches square and gay with red ribbon and seals of wax. There was the document by which Dame Margaret Pulteney of Bath House, relinquished her dower rights to her daughter, the Countess of Bath, under the great seal of the City of London and the signature of His Worship, the Lord Mayor.

What a treasure trove of history in the county clerk's massive safe.

* * * *

Figures of men have cast portentous shadows across the Bath stage during the years.

One was Irish-born George McClure, land owner, speculator, Indian trader, mill owner and probably the first chain store magnate in Western New York. At one time he had stores in Bath, Dansville, Penn Yan and Pittston (Honeoye). He learned the language of the Red Men and conducted trading expeditions into the Indian country. He was a power in politics. But his military career was not glorious. As a general of militia In the War of 1812, it was he who evacuated Fort Niagara prior to the burning of Buffalo by the British.

Some of the Southern settlers brought their slaves with them. One, William Helms of Virginia, had 50 Negroes, but most of them ran away and he found slave holding unfruitful in Northern soil. Helms married the beauteous widow of Major Thornton, but the marriage did not last. Madame Thornton became a legend in Bath. It was said that when she walked across Pulteney Square, men stirred as if flicked by a lash.

John Magee was a poor farm boy who became a multi-millionaire. In the War of 1812, he carried messages on horseback from Gen. Hull at Detroit to Washington. After the war he operated, with a frontier "horse king," Constant Cook of Cohocton, the swankiest stage line of the day. Bath once was the hub of a network of stage coach routes, some of them spanning the state.

Magee was sheriff when Robert Douglas was hanged for murder in 1825 on Gallows Hill, along Geneva Street. Thousands turned out to see the condemned man borne to his doom, seated on his own coffin on a horse-drawn cart, with a military escort. About that execution hangs a somber tale. Assemblyman William M. Stuart of Steuben County tells it well in his "Stories of the Kanisteo Valley:"

"While the people gaped, there came a pounding of hooves along the road that led from Bath. A terrible figure advanced at a gallop. It was a horseman all dressed in black, with a black mask over his face, while his mount also was sable. As he reached the scaffold, he checked his steed, leaned over, pulled a rope and then thundered down the road and no man in all that crowd, save probably two or three, could say who he was. The drop fell and amid great gasp from the crowd, Douglas was snatched into eternity."

Magee had one of the contracts for the building of the Erie Railroad. He helped build the Fall Brook and other lines and became one of the richest men in the Southern Tier. He founded the Bank of Steuben, the stately 115-year-old building on Pulteney Square that now is the Masonic Temple. His former residence is now the public library and the magnate had running water piped to it under the river.

And there was Ira Davenport, merchant-politico, who founded and endowed the Davenport Home for Orphan Girls which still functions.

Bath was the birthplace of John Adams Howell, a distinguished admiral of the Civil and Spanish-American wars and of William Seaver Woods, one-time editor of the Literary Digest. Four generations of the politically potent Campbell family have dwelt in Bath.

And there were merchant princes like Henry Perrine who had a big store near the Pulteney Square and who built a castle-like residence that still stands at Liberty and Geneva streets.

It is said that the oldtime merchants of Bath would be driven to their establishments in their carriages, gloved and top-hatted, and that they never deigned to wait on trade but received their customers as if at a levee.

Once upon a time the Erie rail special trains when grand balls were held in Bath and carpeting was laid from the curb to the scene of the festivity.

Now you know why I call Bath "The Grand Dame." It was an elegant and a spacious way of life that flowered in this shire town.

Most places call their principal thoroughfare Main Street. But not Bath. There it's Liberty Street. Bath is different.

* * * *

The village, 1,100 feet above tidewater, is the trading center for some 25,000 people. Around it is a prosperous farm region, famed for its dairy herds. It is on a branch of the Erie, on the main line of the Lackawanna and is the terminus of the 10-mile Bath & Hammondsport, "The Champagne Route," that links Bath with the wine capital on Keuka Lake.

As before stated, Bath is not an industrial town, Its lone industry is a ladder factory, in a plant that used to make churns. The depression left few scars on the old town.

For 70 years Bath has been the site of the State Soldiers' and Sailors Home, now the United States Veterans Facility. Any organization with a staff of 600 and an annual payroll of $1,250,000 may well be classed as a major industry.

During the Civil War, the state legislature authorized incorporation of a state home for veterans but failed to make any appropriation. In 1872 the GAR revived the project and got another incorporating act but again no funds were provided. In 1875 the state commander of the Grand Army made a militant direct appeal to the people for funds. Many communities chipped in. Bath alone raised $23,000—and got the Soldiers' Home.

Some 25,000 persons saw the cornerstone of the first building laid in June, 1877. The home was formally opened on Christmas Day of that year when 25 Boys in Blue sat down to their holiday repast.

The home's population peak was reached in 1907 when it had 2,143 residents, most of them veterans of the Civil War. In those days blue was the dominant color on the streets of Bath when the old soldiers in forage caps or broad brimmed hats, in gold braid and brass buttons came to town and the drivers of the horse-drawn hacks vied for their custom, at 10 cents the ride.

The population sank to its lowest point in 1928 with only 192 residents. Then the veterans of the first World War began to pour in.

In 1930 the federal government took over the state institution under a 10-year lease and a thorough revamping resulted. Now the home-hospital on the banks of the Conhocton with its 376 acres is a full-fledged government Facility.

In 1936 the trembling hand of a 97-year-old veteran of the Civil War, taken to the scene in a wheel chair, turned the first shovel of earth for a million dollar 430-bed hospital. A fireproof dormitory barrack, and a store house also have been built during the federal regime. But the first unit that was opened with such pomp in 1877 still serves, along with three other barracks over 60 years old, with high-ceilinged rooms, supported by interior pillars. They may have been the last word in the 1880's but today the Bath Facility needs some modern, fireproof buildings to house its veterans.

Veterans of five major wars have lived at Bath, besides those who served in the Indian and border campaigns and peacetime "regulars." The home now has 1,476 "members" as they are called. All who are physically able are assigned to duties. The hospital has 414 patients. Shortage of nurses prevents full use of its facilities.

Only about 30 per cent of the Facility's population are World War II vets. The rest served in the Spanish-American and first World Wars. They come from many states but principally New York and Pennsylvania. They are of all faiths and races, with many Negroes among them. The home's ranks have included doctors, lawyers, scientists and even some newspaper men.

The first woman, a WAVE, was admitted in 1943. The last veteran of the War Between The States to live there, a 99-year-old Cohocton man, died last winter.

Joe Genewich, former baseball pitcher with the Giants and the Braves, is an attendant at the hospital.

The commandant, Col. John L. Spreckelmyer, veteran of both World Wars although he looks still in his 30's, took me on a tour of the plant. He showed me the huge mess hall where 750 are served at a sitting; the bakery and the ice cream plant and all the other units that make the Facility a veritable city in itself.

And there's a silent "city" on the hill where in neat rows are the graves of 5,200 veterans. Each is marked by a simple identical headstone. At each one a flag was placed on Memorial Day. The Facility has a uniformed firing squad and military detail that conducts funerals and other ceremonies with meticulous precision.

* * * *

Come September all roads lead to the Steuben County Fair at Bath. One of the oldest in the state and a genuine country fair, it kept going through the war years. On its half-mile track once trotted the cream, of the Grand Circuit. There is a log cabin containing relics of the pioneer time including bear traps. The Bath Fair is an institution in "The Tier" which would please Charles Williamson who in the year 1795 staged the first fair and race meet on the plains of Bath.

There's no view anywhere finer than that from "Mossy Banks," one of the great hills above the town. Maybe Captain Williamson stood there when he planned his empire long ago.

Ever since a century ago when Adam Haverling gave the site for a school near old St. Patrick's Square, it has been the Haverling High School. Each year, old Bath in England sends a medal to be awarded to the pupil of the Bath, N. Y., school chosen by student body vote as the best student and every Yuletide the mayors of the two Baths exchange greetings across the deep.

That is only one of the traditions that abound in the "far famed city in the land of the crystal lakes."

Despite its glamorous past, Bath at heart is an unspoiled village, democratic and tolerant. I like its serenity.

* * * *

In the Conhocton Valley are other historic villages. To the north there's Kanona, the Indian name for "rusty water," that once was Kennedyville and a noted port. There coastwise vessels were built and floated down the rivers to be sold in Baltimore. After Keuka and Seneca Lakes were connected by a canal and Hammondsport became a thriving port in the 1830's, drovers would stop overnight in Kanona's two big hotels that they might be in Hammondsport at break of day.

There's Avoca, at "the eight-mile tree" blazed by Williamson's woodsmen. For years it was called Podunk until a woman resident on her death bed begged that the name be changed.

Farther northward is Wallace, which used to be known as "The Switch," because when the Erie Railroad was built, Moses Wallace gave the land for a switch. Like Atlanta, it was for a time the boyhood home of Frank Gannett. To the south is the pleasant village of Savona. There's Dry Run, a hamlet, in the town of Campbell where once lived the son of a lumber worker. That boy became a mighty figure in American industry. His name? Thomas J. Watson of International Business Machines.

Linked forever with Marcus Whitman's historic wagon trip over the Rockies that saved Oregon to the Union are the villages of Wheeler and Prattsburg. The latter village was the home of Narcissa Prentiss, the golden-haired girl who married Whitman, the missionary-physician, and who died with him in Indian massacre in the West. In Prattsburg was made the famous Whitman wagon, the first to cross the Rockies.

Dr. Whitman, a native of Rushville, practiced medicine in Wheeler, which was the birthplace of the Rev. Henry H. Spaulding, a member of the Oregon expedition and an unsuccessful suitor for Narcissa Prentiss' hand.

"I'VE been working on the railroad all the live-long day."

That might well be the theme song of Hornell, the brisk city of 17,000 that spills out of its broad valley to climb the sides of the steep Steuben hills.

They call it "The Maple City" because of the many maples that shade its streets. It might well be called "The City of the Iron Horse" for Hornell (it was Hornellsville until 1906) primarily is a railroad town.

Its emblem might well be the familiar black circle on a quadrangular field of white with the word, "ERIE" in its center. For nearly a century, since the first locomotive headlight pierced the darkness of the hills like a star of hope, the destinies of Hornell have been linked irrevocably with the fortunes of the Erie Railroad.

Here is no immaculate, reposeful old town basking in the glories of its past. There is a smoky, roaring, earthy town, with a job to do in the living, throbbing present—to keep the trains rolling, the trains that are so vital to the economy of the nation.

Hornell is a bright page in the romance of the rails. In its sprawling Erie shops, the iron horses are groomed to haul the mile long freights, and the proud express trains that thunder across the land.

In its acres of murky yards is a cacaphony of bells and whistles, clanking couplers, hissing steam and the ceaseless rumble of the rolling wheels.

It is the place of the men in the dark clothes, the men in the long-visored caps who carry dinner buckets. It is the place where the houses around the tracks are painted in dark colors against the smoke. It is the place where the housewife has to "call Ed at noon because he's taking No. 8 out today." It is the place where the grog shops face the long old red station and the maze of tracks. But Loder Street is not as gaudy as of yore when many red lights, other than those of the lanterns dancing in the yards, beckoned the men of Erie.

This city on the Iron Trail has led no sheltered life. It has known the wrath of mobs when strikes raged along the tracks. It has felt the devastating wrath of the flood waters roaring down from the hills on the vulnerable valley. It has an indomitable spirit in the tradition of the railroader that "the train must go through." It is rich in community enterprise and civic pride.

There is much more to Hornell than the Erie Railroad and the car shops although they are the bulwarks of its economy. The city has other industries, important ones. Hornell is the trading center for a large farming area. Its shopping district does not straggle down one main street but covers four busy thoroughfares.

Although it lies in a valley, Hornell is 1,150 feet above sea level. Some of its streets climb precipitous hills that rise 500 feet above the town. Many houses rest on lofty terraces, which was a fine thing in flood time. But I would not like to be a mailman in Hornell in humid midsummer.

* * * *

The first white settler was Benjamin Crosby who in 1790 cleared the present site of the St. James Mercy Hospital in Canisteo Street. His nearest neighbor was an Indian named Straight Back who lived in a wigwam near the present Seneca Street bridge.

Crosby invited Straight Back to dinner and served the meal in courses. The Indian returned the invitation and when the white man sat down in the wigwam, the meal was also in courses—each one of the same dish, succotash.

Crosby invited Straight Back to dinner and served the meal in courses. The Indian returned the invitation and when the white man sat down in the wigwam, the meal was also in courses—each one of the same dish, succotash.

The settlement was first known as Upper Canisteo because it was on the old Indian river of that name. The present village of Canisteo was called Lower Canisteo. Upper Carnisteo was renamed Hornellsville in honor of George Hornell who came in 1792 with a considerable retinue of slaves and bought several thousand acres. He set up grist and saw mills, opened the first store and inn and became a judge.

Lumbering was an important pioneer industry and down the Canisteo to the Chemung to the Susquehanna to Chesapeake Bay the great raft-arks carried not only lumber but also cattle, cheese and wheat to Baltimore. The first ark went down the river in 1800 from the village north of Hornell that ever since has been called Arkport. The pioneer ark owner was Judge Christopher Hurlbut whose home, built 142 years ago, still stands in Arkport.

The advent of the Clinton Ditch and other canals doomed the river traffic and the Southern Tier languished—until the Iron Horse came.

In 1832 an ambitious project was spawned, the building of a railroad from the Hudson to Lake Erie. Early surveys put little Hornellsville on the line. But it was many a year before the New York and Erie Railway, always floundering in troubled financial waters, came to the Canisteo Valley.

Its advance guard appeared in 1841 in the form of a machine that was a combination pile driver, steam locomotive and a saw mill. It moved on wheels, drove two piles at a time and sawed them off at the level as it passed.

The first Erie train puffed into Hornellsville in September, 1850. It was hauled by the famous little old Orange Number 4, the trail blazer for the Erie which had won a 20-mile race with a stage coach. At that time the village, already quickened into new life by the railroad, had 100 houses, two churches and two schools. The center of things was Cobb's Hotel at Main and Canisteo Streets. a mecca in stage coach days.

Finally the Erie inched its way over the formidable hills of the Southern Tier until it reached its western terminus, Dunkirk, and the first trunk line in America was completed.

May 16, 1851 found Homellsville gay with flags and bunting. The first passenger train to traverse the entire length of the Erie steamed into town and after cheers, oratory, dining and toasts, changed engines and resumed its triumphal tour. Aboard were Millard Fillmore, president of the United States, and three members of his cabinet, including Daniel Webster, secretary of state, besides an array of senators and governors, and of course, big Ben Loder, president of Erie. "The Godlike Daniel" stole the show. The great orator rode in a rocking chair lashed to the platform of a flat car that he might better view the scenery.

Hornell had been chosen as an important cog in the Erie machine even before the road was completed, and the first car shops were built in 1849 on the site of the old militia drill grounds. The next year they were enlarged.

When in 1852 Hornellsville became the southern terminus of a branch line to Buffalo and a busy junction point, the village began to boom in earnest and fortunes were made in real estate. The first car shops went up in smoke in 1856. But larger shops already were under construction at the time and the new plant was dedicated with a grand ball later in the year. Since 1928 all the heavy repair work of the Erie system has been concentrated in the Hornell shops with its 27 great bays to handle that number of locomotives at one time.

Some 1,200 men are employed in the shops, to say nothing of the hundreds who man the train crews and work in the yards. Right now the increasing use of Diesels by the Erie poses a big question mark in Hornell. the city of the sprawling car shops. For Diesels need few repairs.

There have been strikes at Hornell but over the years the railroad labor relations picture there is a bright one. The most serious disturbance was in 1877, in the wake of a 10 per cent wage cut. After some switches had been spiked and tracks torn up by unruly mobs, the militia was called out to patrol the yards. Among the troops sent to Hornell were the men of Rochester's 54th Regiment. Their blue uniforms awed the strikers who thought the 54th was a regular army outfit.

In 1888 Hornell became a terminus of the Pittsburgh, Shawmut & Northern Railroad. After 42 years in receivership, this road, which rambled over 180 miles of the Southern Tier and Pennsylvania, gave up the ghost in 1947.

When Mrs. Clara Higgins Smith, widow of a former president of Shawmut, died in New York a quarter of a century ago, she left half of her six million dollar estate to the American Red Cross. The bequest included the 10-mile Shawmut branch from Hornell to Moraine Park, once an excursion mecca, now an Elks recreation park. The Red Cross never cared particularly about owning a railroad and after the Shawmut's demise, sold the branch to the Erie. One of Hornell's leading industries is served by the former Shawmut line.

* * * *

For years Hornell has been a silk and cloth making center. In 1890, Frederick P. Merrill, with the Rockwell brothers, started the first silk mill, a small one. The industry grew and reached out into the glove manufacturing field. Merrill sold some plants and started new ones. One of his mills turned out the first chiffon woven in the United States. When foreign sources failed with the advent of World War I, he captured the American market in artificial suede. The Hornell mills did a booming business. In 1920 at the peak of his career, just as he was about to start producing "tubize," the forerunner of the modern rayon, Merrill died. Today Hornell has a Merrill silk hosiery plant but no glove industry.

Other Hornell industries in the fabric field are Huguct Fabrics, Dolores Dress Company, Hornell Industries, which prints and dyes dress materials, and De Witt & Boag. To add diversity to the list there are the S. K. F. Industries, makers of ball bearings; the Hornell Woodworking Company, the Hornell Brewery and an ice plant for refrigerating railroad cars. A live Board of Trade is on the alert for new industries. Factory space is at a premium in the Maple City.

* * * *

Four streams pour down from the wild steep hills to join the main waterway in the valley, the Canisteo River. They are the Canacadea, Crosby Creek, Chancey Run and Big Creek. Ordinarily they are placid streams but swollen by rains or spring thaws, they become raging torrents. From its beginning Hornell in its vulnerable basin among the hills has been plagued with floods.

The flood of floods struck in 1935. On Sunday, July 7, a cloudburst smote the Southern Tier and the Finger Lakes country. Morning found two-thirds of Hornell under water, 6 feet high in places. Two persons were drowned. Property damage was enormous. Hundreds of families were marooned and boats patroled the streets. Highways were blocked and the main line of the Erie was under 5 feet of water. Water mains were broken, causing a serious health hazard. At night the city was in darkness.

Hornell was a stricken city, hardest hit in all the state. Its mayor appealed for food and clothing for the homeless for whom public buildings were thrown open- Martial law was declared and National Guardsmen from all over Western New York poured into the city of wrecked buildings and yellow mud. The Red Cross and other relief agencies went into action and 1,000 refugees were cared for. Governor Lehman and other officials came to see the devastation with their own eyes. Gradually Hornell emerged from the slime of the great flood.

Since then tremendous steps have been taken to prevent a repetition of the 1935 disaster. Under the aegis of Uncle Sam, the streams have been deepened and widened and retaining walls built. A huge earth darn that backs up the waters three miles was completed near Arkport in 1941. Another dam near Almond is under construction at a cost of $3,200,000. In all more than $7,00O,000 has been spent on flood control around Hornell. That sum approximates the estimated damage caused by the big flood of 1935.

Already these measures have proved their worth. Hornell has escaped unscathed when recent floods have swept the "Tier." For the first time in its long history, the city where the creeks rush down from the hills feels secure when the rains come.

* * * *

The Erie Railroad cutting through the heart of the town presents a traffic problem but you won't find more careful or courteous motorists anywhere. When I mentioned that fact to Mayor Ernest G. Stewart, he proudly displayed a certificate showing Hornell had won third place among cities of its population class in a national pedestrian protective contest.

Stewart, a Democrat, has been mayor off and on since 1937. Steuben is one of the banner Republican counties of the state, but in the railroad city of Hornell, the Democrats often win elections. Right now the Council is divided 6 to 6 politically.

Here is some Maple City miscellany:

The shady square, Union Park, in the heart of town was set aside in 1832. Hornellsville became a city in 1888.

The population of Hornell is 87.5 per cent native white.

The old Hornellsville Fair Grounds have been transformed into Maple City Park with swimming pools, tennis courts, ball diamonds and other recreational facilities. The fair folded its tents around 1929 and from its old grandstands now baseball fans watch the PONY League teams compete.

Big Ed (Porky) Oliver, one of the nation's golfing greats, prior to 1941 was the "pro" at the Country Club in North Hornell.

Landmarks of Hornell—the bell tower of the old red firehouse that abuts the modern building housing the city offices . . . the baronial National Guard Armory that has been on Seneca Street since 1895, with the cannon balls lining its sidewalk entrance . . . the oldest building in the city at 34 Main Street, Stacy L. Jackson, city historian, said, is the combination store, postoffice and residence that Ira Davenport built in 1828 and which now is a doctor's office and home . . . the towering Hartshorn hill west of the city . . . the public library where Miss Helen Thacher, an authority on local history and the descendant of pioneers, presides. . . . (Hornell claims to have established the first village library in Western New York in 1868) . . .

* * * *

It is hard to believe that Canisteo, comely village of 2,800, set among majestic hills south of Hornell, once was an outlaw stronghold.

There in the 17th and 18th Centuries lived a motley land of the lawless of all races: Indians of all tribes, renegade Frenchmen, scoundrelly Dutchmen, Yankee fugitives from justice, runaway Negro slaves. They cleared enough valley land to build some 60 large and well made log houses.

The French in 1690 sent an expedition under Sieur de Villiers to "Kanisteo Castle." The outlaws fled at the approach of the invaders who, after unfurling the flag of France, and celebrating Mass, departed.

Soon the outcasts returned to their stronghold. British Army deserters joined them and two forts were built to protect the "Castle." In 1786 two Dutch traders, subjects of Britain, were waylaid and slain there. Two years later, Sir William Johnson, lord of the Mohawk Valley, sent a party of 140 men under the halfbreed Captain Andrew Montour to destroy the wilderness vipers' nest. Again the occupants fled and this time the invaders burned the houses, killed the livestock and blotted out the refuge of the lawless.

In 1788 Solomon Bennett, John Jameson, Uriah Stephens and Richard Crosby came from Pennsylvania and "discovered" the lovely Canisteo Valley. They formed a pool of 12 men, many of them survivors of the Wyoming, Pa., Indian massacre, and bought a tract from Phelps and Gorham.

The next year settlement began at "Lower Canisteo." It was a wild and wooly place and Assemblyman William M. Stuart of Canisteo, a genial gentleman and a painstaking historian, tells in his book, "Stories of the Kanisteo Valley," how the stage coach drivers would whip up their horses and dash through the unruly town. "The Canisteers," as they were called, shocked Bath with their antics when they visited the decorous shire town.

When British invasion was feared during the War of 1812, Col. James McBurney led his Canisteo brigade to Dansville where the militia from other towns had mobilized. When it was learned that the invasion fears were groundless, the "Canisteers" tapped the barrel of whisky they had brought along. There ensued so fierce a brawl among the rival companies that it was called "The Battle of Dansville."

That same Colonel McBurney built on the Canisteo-Hornell Road a noble frame residence in 1797. It is still standing, the oldest building in the Canisteo Valley. The old home, with 17 rooms and many fireplaces, has a front door of solid walnut with fan shaped windows above it. On the third floor was the ball room where the Wadsworths of Geneseo and other visiting gentry were entertained in the long ago.

The man who built that mansion was a slave owner. It is ironical that later occupants of the historic home maintained there a station of the Underground Railway which spirited runaway slaves to freedom.

THE stage hands have shifted the scenery since our last Stage Coach stop.

Gone is the dramatic Southern Tier backdrop of majestic towering hills. In its place is a setting; that casts a gentler spell. The diversity of its pattern is one of Western New York's greatest charms.

Our four horses are trotting steadily across a level terrain, a fertile, smiling land, dotted with the green of bean and cabbage fields. Red apples are ripening in the September sunshine. Far behind are the rugged Steuben hills of last week's stand. Nov we are rolling across the eastern reaches of Ontario, mother of all Western New York counties.

We are on the "home stretch" of our tour but before our stage coach goes back among the cobwebs of the past, its trumpet will sound through many a pleasant village in the old Indian country that lies between the Clinton Ditch and the land of slim blue lakes.

Our first stop will be at the old village that bears the name of the New Englander who once was co-owner of all of York State west of Seneca Lake, Oliver PHELPS.

* * * *

Tourists will remember Phelps, N. Y., as the spruce village with the long main street that dips in its center as it crosses a murmuring stream.

They're likely to recall the big billboards at the village portals that proclaimed the home of "the world's largest producer of sauerkraut."

They're likely to recall the big billboards at the village portals that proclaimed the home of "the world's largest producer of sauerkraut."

And they could hardly miss the sign on the old stone hotel : "Ye Old Tick's Inn of Country Lawyer Fame."

Thousands who never saw Phelps, N. Y., feel they know the place because of three books written by a native son, Edward Bellamy Partridge. To the home folks he is "Ed." The "Country Lawyer" of the book of that name was "Ed" Partridge's father, "Big Family" was the Partridge clan and "Excuse My Dust" chronicled the author's boyhood memories of the early days of the horseless carriage. The locale of the three best sellers is the same—Phelps. N. Y.

Bellamy Partridge's pen did not put Phelps on the map. It merely outlined his home town in bolder letters. Phelps was put on the map a century before Bellamy Partridge was born. The man who put it there was a hardy pioneer named John Decker Robison.

In May, 1789, a flat boat brought Robison, his wife, his eight children and his worldly goods to the wild lands on the Canandaigua Outlet (near the eastern boundaries of the present village) that he had bought from Phelps and Gorham. Robison came from Columbia County and all the way from Schenectady on the Mohawk he had followed the water routes to his new home. The trip took two months.

A cloth tent they had brought along was the Robison's home until a log house could be built. At first their only neighbors were a few curious Senecas. Soon other settlers came and by 1791 there was quite a colony. Some Marylanders came with slaves but most pioneers were of New England stock.

An early arrival was Seth Deane, whose land embraced the pre-cut Town Hall site and who built the first grist mill and saw mill on Flint Creek, the stream that crosses Phelps' Main Street before it joins the Canandaigua Outlet. Mrs. Deane made the first cheese in the region in an old-fashioned outdoor press. All her labor went for naught. A hungry bear came along in the night and devoured every morsel.

At first the settlement was known as Phelpsburg. Then briefly it was the District of Sullivan, in honor of the Revolutionary general whose raid broke the Seneca power and paved the way for settlement of the Genesee Country.

In 1796 there was a gala party and a barbecue at the frame tavern that Jonathan Oaks had built three years before at the crossroads that still is called Oaks Corners. The occasion was the organization of a new township which was named Phelps, to the delight of the guest of honor at the party, Oliver Phelps.

Oaks Corners became one of the liveliest places on the frontier. In 1816 a race course was laid out there that drew noted horses from the East and South and hundreds of spectators. Today Oaks Corners, three miles southeast of Phelps on the Geneva road, is a quiet hamlet save for the clangor of the big stone-crushing plant along the tracks.

Descendants of Jonathan Oaks still live at the "Corners" he founded 154 years ago. His great-great grandson, Nathan Oaks Jr., still owns the original Oaks land purchased from Phelps and Gorham and Carlton V. Oaks lives in the noble brick house with the pillars that was built in 1832 by Col. Elias Cost, who married into the Oaks clan.

On the banks of Flint Creek and the Outlet, mills sprung up and the site of Phelps became a thriving center. At first it was called Vienna after the Austrian capital. Really there were two Viennas, bitter rivals. The west-end of the present village was called West Vienna, Old East Vienna is now the business section of Phelps.

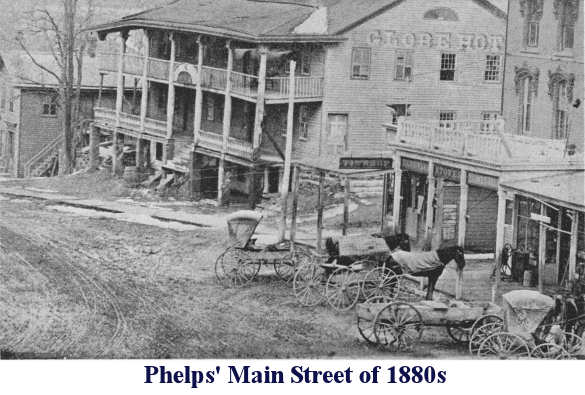

It was a busy place with many taverns in Stage Coach Days, when it was a stop on the Buffalo-Albany run, and huge wagons, drawn by four or six horses, hauled the goods of the frontier across the state. Pioneers heading west in their covered Wagons also stopped at the inns of Vienna.

Because there was another Vienna in the state, the village was renamed Phelps in the 1840s. In the nearby Wayne County villages of Newark and Palmyra there are still streets named Vienna. By the way, oldtiniers pronounce it "VYenna."

* * * *

July 4, 1841 was a great day for Phelps. Hundreds turned out to see the first train steam into town on the new Auburn and Rochester Railroad (now the New York Central's "Auburn Road"). At first there were two stations, one, with a restaurant, at West Vienna: and the other at East Vienna. Long ago the west end became a part of Phelps and its depot went down.

July 4, 1841 was a great day for Phelps. Hundreds turned out to see the first train steam into town on the new Auburn and Rochester Railroad (now the New York Central's "Auburn Road"). At first there were two stations, one, with a restaurant, at West Vienna: and the other at East Vienna. Long ago the west end became a part of Phelps and its depot went down.

The advent of the Iron Horse boomed Phelps and brought industries. Once there were 22 passenger trains a day on the Auburn Road. Now there are only two each way.

Travelers will remember the Phelps station because of the statuary fountain on its lawn. For many a year the two sculptured youthful figures have stood there amid the fountain's spray. A green and red umbrella over them adds little to the artistic effect.

The first settlers found the Ontario County soil rich and good. It is particularly adapted to the growing of beans, cabbage and wheat. In other days there were two other rather unusual crops. Phelps once was a center of the peppermint oil industry and at the turn of the century acres of mint beds flourished on the flats. Also wormwood was grown and processed there.

Phelps has always been an industrial village, as well as one of trim residences. It has produced a wide variety of articles. Once there were seven malt houses in the town. The Bowker hearse and wagon shops, the big Crown Drill plant that shipped agricultural implements to far places; a threshing engine plant, a shoe factory, a basket factory and a distillery—they are some of the Phelps industries of yesteryear.

Now "the time has come to talk of many things" including cabbages and a "sauerkraut king."

In 1901, 31-year-old Ohio-born Bertram E. Babcock came to Phelps with a bicycle and $1,200 in borrowed capital. He had worked his way through Wooster College, a Presbyterian school in Ohio and after graduation had learned kraut making in a Clyde, Ohio, plant. He started a small plant in Phelps. In 1907 he joined forces with the late L. S. Foster, who had been a vinegar manufacturer in Holley and they formed the Empire State Pickling Company. Until 1916 they produced only barreled kraut. Then canning came into vogue and the firm flourished and expanded. In 1920 Foster sold his interest to Babcock, a shrewd industrialist, who remained sole owner until his death in 1941.

By that time Empire State had become the largest producer of sauerkraut in the world and Babcock who had come to Phelps 40 years before with a bicycle and $1,200, was widely known as "The Sauerkraut King." He had built a stucco mansion on Main Street, a replica of a residence in Rochester's East Avenue that he admired. His will generously remembered his Alma Mater, Wooster College, and several employes.

Today Empire State, of which John M. Stroup is president, has seven plants, two in Phelps and others in Shortsvillle, Junius, Gorham, Reed's Corners and Waterport. During the last war it produced over half a million cases for the government. It makes its own cans. It employs both men and women and is a year-around industry, although busiest in the fall, when the farmers' wagons, piled high with cabbage, line up at the plants, each waiting its turn on the huge scales.

Phelps also is the home of the Seneca Kraut Company, whose large factory is on the western edge of the village.

Other present day industries are the Grange League Federation's bean plant that is important to the village economy because it draws farmers to town; the Wright-Hibbard plant which makes light electrically-propelled factory trucks; the Phelps Manufacturing Company, a machine shop; the Finger Lakes Paint Manufacturing Company, and the Halsey Boat Works.

In the early days of the century Charles A. Lane made three-cylinder "gasoline buggies"—for his own use.

* * * *

The national spotlight swung on the Ontario County village of some 1,500 people in 1939 when the delightful simplicity of Bellamy Partridge's book, "Country Lawyer," took the reading world by storm.

Partridge, who had practiced law in Phelps for 10 years before he went west for reasons of health and became a newspaper correspondent, editor and author, drew on the papers of his father, Samuel Selden Partridge, and his own memories for material when he wrote his engaging portrayal of rural life.

"The Country Lawyer" practiced law in Phelps for more than 40 years after his arrival there from Rochester in the late 1860s. Villagers recognize many of the characters, as the law cases were actual ones although the names of the principals are disguised.

A fascinating character in the book is "Old Tick" who ran the inn. His real name was Joe Ticknor and he is well remembered for his eccentricities. He weighed 250 pounds and always wore carpet slippers. He would never use a telephone because he "wasn't going to talk to people he could not see." A couple registering at his hotel virtually had to produce a marriage certificate.

"Tick's" old inn is still there as its sign so conspicuously attests. The three-story stone hotel was built in the 1860s with all the Victorian trimmings, including balconies. Now it has one bar where "Tick" had three, one in the basement, another on the main floor and a third upstairs.

There are many other landmarks identified with the Partridge books. The old brick law office, one of those one-story buildings with pillars that once were so common and now have all but vanished from the village scene, still stands on Church Street. The shingle of John B. Parmalee, who practiced law with Bellamy there, now hangs where Samuel Partridge's did. Parmalee showed me the butternut desk with the famous secret panel; the sturdy, old fashioned chairs in which sat the clients of "The Country Lawyer"; the massive cast iron rack on which he hung his stove pipe hat and his old law books on the shelves.

At 106 Main St. is the square old Victorian house, painted a chocolate color, where lived "The Big Family" of the book, the ten Partridges. Reminiscent of horse and buggy days are the two hitching posts on the lawn.

Diagonally across the street from the homestead lives Bellamy Partridge's sister, Mrs. Elizabeth Howe, widow of Dr. William A. Howe, long connected with the State Department of Health. The author, now a resident of Connecticut, pays an occasional visit to the home town he made famous. Incidentally he wrote 12 books before he finally "clicked" with "Country Lawyer." So in a way Phelps made him famous. Anyhow the home folks still call him "Ed."

* * * *

Another native son achieved fame in a way hardly to be emulated. His name was J. Grant Lyman and a quarter of a century ago, long after he had left Phelps, he was regarded as one of the slickest confidence men in America, a "Get Rich Quick Wallingford," who sold non-existent factories and real estate. The law caught up with him and he went to San Quentin prison. He escaped and was captured in the California mountains. Lyman wound up selling pro-grains and pencils at the Empire City Tracks in New York. Nearly a decade ago he came back to Phelps, to rest in the village cemetery.

Native sons of whom the village is much more proud were the late Supreme Court Justice Robert F. Thompson of Canandaigua and the late Monsignor John P. Brophy of Rochester. A distinguished present-day resident of the town where his ancestors settled in the 18th Century is Earle S. Warner, Supreme Court justice and former state senator.

Giving distinction to the village are its many cobblestone and cut stone buildings, more than a century old. The cobblestones were hauled in stone boats by the pioneers from the shores of Lake Ontario, some 20 miles away.

On the highway east of the village are a number of the old stone houses. The stately one of cut stone farthest east was built in 1816 by General Philetus Swift, a veteran of the War of 1812 and a leading citizen of his time. Another picturesque landmark is the cobblestone Baptist Church.

The Town Hall of cut stone was built in 1849. In that venerable building I was fortunate to find a trio who knew well the Phelps of yesteryear. One was Frank A. Post, the veteran town clerk. Another was Orson H. Dewey, town assessor who was working on the tax rolls. And tall Stewart D. Prichard, an authority on the lore of his native village, dropped in with a huge double tomato. The town clerk's office is a sort of repository for old pictures and village curios.

* * * *

In 1864 a series of incendiary fires destroyed most of the business district. It was then, as told in "Excuse My Dust," that "Old Ocean," the fire engine that was pumped by hand and drew its water from a cistern in the middle of the street, failed to negotiate the gentle but then ice-glazed incline west of Flint Creek.

An exciting day was June 8, 1939, when two bandits strode into the Phelps National Bank during the noon hour, forced the cashier and two customers into the cellar at gunpoint and escaped in a waiting car with $4,000 in cash. They never were captured.

August, 1939 saw a week-long; celebration of the sesquicentennial of the village's settlement. There were parades, pageantry and speeches and former residents came in droves, some from great distances, for the birthday party. Erwin Spafford, editor of the Echo, struck off the scrip in 5, 10 and 25-cent denominations that was sold as souvenirs to help finance the celebration, which was called "The Conquest of the Years."

The years that Phelps have conquered rest lightly on her shoulders. With her shady streets, neat lawns and old homes, Phelps has a New Englandish air, But there's no Yankee austerity or stiffness about Phelps. A breezy, spontaneous spirit of friendliness pervades this personable old town in the land of beans and cabbages.

To Next chapter

![]() To GenWeb of Monroe Co. page.

To GenWeb of Monroe Co. page.